Where He Is Now

Carl Wolfgramm (‘16), after being devastated by a career-ending health implication in eighth grade, discovers his new passion to fill the void of sports. Remaining positive, Wolfgramm shares his story with The Viking.

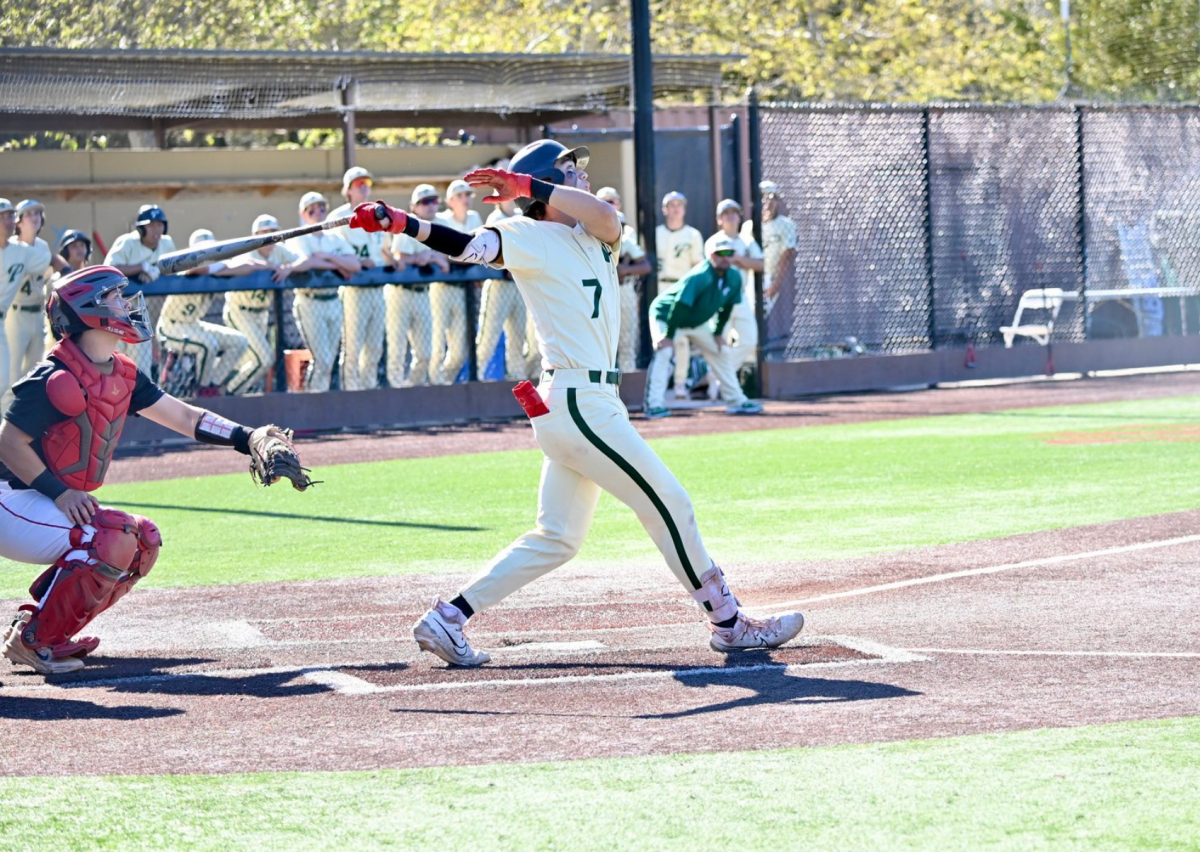

Carl Wolfgramm (’16) reminisces on what could have been if he didn’t have his stroke.

November 12, 2014

For top-flight athletes, one false step can bring injury. Some athletes are sidelined for minutes, some for games and some even miss whole seasons. But, there are a few cases through all levels of sport where an injury or health issue can end a promising career prematurely. In just a few brief but heartbreaking words, a doctor can ruin the dreams of a young aspiring athlete with the simple words no athlete wants to hear: “You can never play again.”

Most casual sports fans recognize the famous Lou Gehrig case: after a legendary 17 year career in which, for 13 years, he did not miss a single game, Gehrig was forced into retirement by Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), an eventually life-ending disease which now bears his name. He was a seven-time all-star, two-time American League Most Valuable Player, and finished his career with a .340 batting average, 493 home runs, and 1995 runs batted in. In a special ceremony, the 36-year-old Gehrig was inducted into the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame. He died one year later, at age 37.

Joe Theismann, two time Super Bowl-winning quarterback for the Washington Redskins from 1974-1985, had his career cut short by one of the most violent and disturbing plays in football history. On a Monday night game, New York Giants linebacker Lawrence Taylor sacked Theismann, and in the process of bringing him down inadvertently snapped his leg in two. Theismann was carted off the field, and never made it back into an NFL game again.

Gehrig is known as one of the greatest men to ever play baseball, despite being forced to end what could have been the greatest Major League career in history. Theismann, although not a statistical superstar, would most likely have been able to guide Washington back to the playoffs if not for his injury.

Unfortunately, the experience of career ending physical conditions and injuries is not isolated to professional athletes.

High School career ending injuries have greatly increased over the past few years. Carl Wolfgramm (‘16) knows first-hand the reality of never being able to step on his playing field again.

The date was November 23, 2012. Wolfgramm, an 8th grader at Jordan Middle School at the time, was casually playing basketball with his friends, Eli Givens (‘16) and Tony Cabaillero-Santana (‘16), in the Jordan gym. Suddenly and unexpectedly, he suffered a stroke extremely rare for his age.

“We were playing a game and [Wolfgramm] was shooting the ball,” Givens said. “He kept shooting and kept missing and he was shooting pretty close up, but wasn’t even hitting the rim.”

Givens and Cabaillero-Santana thought it was weird, but did not give it too much attention. They continued to play around, but Wolfgramm’s state only became worse. Givens checked in with Wolfgramm just to be sure, and Wolfgramm claimed he was okay.

“Tony was getting the ball and I asked, ‘Hey Carl, are you okay?’, and he just responded, ‘Yeah, I’m fine,’” Givens said.

“I turned around and walked back to go shoot and he said, ‘I can’t’.’”

“He dropped the ball and just stood there. He turned around and looked at me and said, ‘I can’t feel half my body.’”

Unusual circumstances, Wolfgramm says, contributed to the stroke.

“I was very dehydrated, and my blood pressure had risen dramatically at the time,” Wolfgramm said. “I stopped playing, but was just watching them play, fully conscious. I remember everything that happened.”

Luckily for Wolfgramm, several of Jordan’s lunch supervisors were close by.

“They noticed that I had gone very stiff, and that the left side of my face was hanging down,” Wolfgramm said.

Paramedics were contacted, and Wolfgramm was taken to Stanford Hospital. Diagnosed with a stroke, dehydration and high blood pressure, Wolfgramm was given terrible news: “They told me that I could not participate in any sport with collisions or head contact,” Wolfgramm said.

The news was heartbreaking to not only Wolfgramm, but also his support system. To see such a young, promising athlete have his career ended at such a young age hit home with his friends, who also were pursuing careers in football.

“He would have been a star,” Givens said.

Prior to the incident, Wolfgramm was very seriously considering attending De La Salle High School in Concord, Calif. The Spartans, a perennial football powerhouse, are currently seated as the number three high school football program in the nation and number one in the state. Unfortunately, after his stroke, going there seemed a little impractical and would not work out for the young athlete.

By now, Wolfgramm would have been a starter for the Spartans, anchoring down the defensive line. Given his size (6’4”, 275 lbs) and athleticism, Wolfgramm would have fit the mold of a Division-1 defensive end.

“I am very confident that I would have been a four or five-star recruit had I not had my stroke,” Wolfgramm said.

It was well known that Wolfgramm would have advanced in football. Cabaillero-Santana and Givens both currently play football at Paly and knew Wolfgramm would have been a star football athlete.

“He would have been at De La Salle,” Cabillero-Santana said. “He would have been a whole, totally different person.”

Wolfgramm, too, had ambitious goals. After playing at a Division-1 school, he wanted to continue his career at the next level.

“Football was a sport that I had a passion and heart for,” Wolfgramm said. “My dream was to go on one day to the NFL as a first round pick.”

“Once the doctors told me I could no longer play football, I thought it was the end of the world. But when I got home, I kept thinking about it, and I thought ‘It’s not the end of the world, there are a lot of different fields out there that I can be successful in besides football,’” Wolfgramm said.

Maintaining a positive attitude, Wolfgramm changed his focus from athletics to academics and a new extracurricular: theater. As a Polynesian, Wolfgramm finds it odd and unfair that so many young men in his culture are pushed towards sports as a career.

“I think that it’s sad that people think sports are the only way to help out their families,” Wolfgramm said.

He went on to explain that, while many Polynesian boys are very athletically inclined, few are given opportunities to branch out and explore other activities that they might be even better at.

“I find it unfair for a parent to raise a child to live a life exactly the way a parent wants the child to live it,” Wolfgramm said. “They should let the child choose what he or she wants to do in his or her life.”

Wolfgramm became involved in Theater when he came to Paly. He started by signing up for the theater course, and started getting involved in school plays. He says the reason he chose a path in theater was because he could easily draw comparisons to football, likening the pressure of performing to the intensity of the sport he once played. Recently, he acted as the the giant in Paly theater’s performance of The Stinky Cheese Man alongside Daniel Cottrell (‘16), who played the lead.

Cottrell and Wolfgramm, now close friends, first met in an advisory class.

“He introduced himself to me since I was new and he was friendly,” Cottrell said. “He’s very willing to listen and really doesn’t judge you.”

Wolfgramm, having started his theater career a little later than most, has had to work slightly harder than his contemporaries to develop the difficult techniques of line memorization and on stage acting, but Cottrell thinks he is on the right track.

“He is perserverant,” Cottrell said. “He is very open to constructive criticism. Though he is not at a superstar level yet, he certainly has the right attitude and disposition to be able to improve quickly.”

Wolfgramm wants to continue to broaden his horizons and expand his theatrical talents.

“In the future, I want to take choir so that I can learn how to sing and join in some musical plays,” Wolfgramm said.

More importantly, Wolfgramm has found happiness in what he is doing now, whereas some would still be upset over a career ending injury.

“I’m really enjoying theater right now,” Wolfgramm said. “My aspirations are to become a famous actor an I am really enjoying my journey.”

At the time, Wolfgramm thought of his stroke as a disastrous event. Now, though, he views it as a blessing. If he hadn’t had his stroke, he is sure he would still be playing football, and never would have discovered his love of acting.

“I think that this is sort of a testimony for me,” Wolfgramm said. “There is a reason why I had that stroke, so I could try out different things besides football.”

Another blessing that Wolfgramm feels his stroke has brought is a realization of the importance of education. With a sad look, he described the problem.

“Many people who go to Division-I colleges to play football don’t appreciate the education. All they can think is football, football, football,” Wolfgramm said. “If they don’t make it to the NFL, they end up having to do undesirable work, like landscaping.”

Though Wolfgramm looks to make a career in the performing arts, he knows the importance of higher education. “As a backup plan to theater, I want to major in economics, because I am very good with handling money,” Wolfgramm said.

However, Cabaillero-Santana, having seen Wolfgramm grow and develop as a friend and actor, has no doubt that he can make theater a career.

“I think whatever he does he will put everything into it, that’s the kind of person he is, and if theater is it then he is going to give his all,” Cabaillero-Santana said. “Something great is going to happen”.

As a genuinely kind person and loyal friend, Wolfgramm should see nothing but success in whatever he chooses to do. He wants his story to not be defined by what could have been, but what he is now.

“I want everyone who reads this to see it as sort of an inspiration,” Wolfgramm said. “In life, there are a lot of open doors and dreams out there other than football.” <<<