Three horns pulse. A cardinal flag tails an adrenaline-pumped college kid as he blazes around an oval. The crowd roars and claps as a fight song plays and trees and dolls come alive. A loud “thud” reverberates. The three horns pulse again.

In what seemed like a simple touchdown to a spectator at a Stanford football game, it was like living a fantasy for me. These football games were the most enthralling events in my childhood. On a Saturday afternoon, there was rarely a time where I wasn’t at a game. I would skip the jump-house, the magician, and even the circus to get to suit up in my cardinal red shirt and white snap-back.

But it wasn’t just Stanford football that I loved. On Sunday, I had the same dedication watching the Montana-cursed and Owens-traumatized 49ers on TV. It was all about the football.

The hitting, the tackling, the battling, the throwing, the catching, the running, the kicking. All of these things happened in a few hours on a football field. I wanted nothing more in my life than to be a part of it. Flag football as a six year-old wasn’t nearly enough, and tackle football had my name written all over its shoulder pads.

After a reluctant half-nod by my mom which easily could have meant no, my dad signed me up to play for the Palo Alto Knights, a Pop Warner organization and a power-house in the Bay Area. I got my football gear, and though it was all a little big, I figured it would suit me just fine. As I was looking forward, I thought that the next day would be the best of my life.

Greg Beratlis. I still remember that name even though it was 11 years ago. That was the name of my first ever football coach, and he made his presence clear on the first day of practice. I thought football was going to be fun and easy because I figured it was like all the other youth sports. In these sports you have your practice where you basically do nothing and just have fun, then you have your games, and then you have your snacks; the latter of which seemed the most appealing to all the little kids that were playing. Football was different.

I didn’t get to be the quarterback or a wide receiver, instead I started out on the offensive line. Even though my dreams of being the next Randy Fasani at Stanford were shot down, Beratlis did not care. He seemed to do it with ease, breaking both mine and everyone else’s hearts who thought they could play quarterback. Even though it was his first day coaching youth football, it sure seemed like he had done it for a long time. In fact, I am not sure if he was even coaching. He seemed more like a drill sargent.

That first day of football could very well have been the best and worst day of my young life. I finally was able to play, but I began to realize how much I hated football practice. The conditioning was horrible. I never knew I could do so many sprints. I was hoping my legs would fall off so I wouldn’t have to do any more. We only had one water break. The rest of the time our helmets had to be on our heads and they weighed 10 pounds; at the time I think I weighed about 70.

Practicing three hours every day for four weeks was absolutely horrible. I hated football so much I would tell my mom I wanted to quit on the drive over before every practice. Yet, at the end of the four weeks, I got to play in my first game. Finally, I wasn’t hitting the same guys. It was something new, and it was the most fun I had ever had in my life.

The first hit I ever smacked in my life was in a scrimmage against the Menlo-Atherton Vikings. I was aware that they were in Division II while our team was in Division I. To me, I didn’t really understand the difference until game time. It was the first play of the game on offense, and I piled into the huddle at left guard. The first play was a sweep to my side. The kid lined up across from me looked like he was scared out of his mind. I guess what Beratlis did for me in the preseason worked out for me after all; I had the crap beat out of me long enough that I didn’t fear my actual competition. The ball was snapped and I flattened the tackle and then flattened the line backer, and then there was no one else to hit. We scored.

Though I thought I did everything right, Beratlis yelled like there was a fire on the field. He came running and screaming up to me, but I couldn’t really understand him too well. From what I could tell though, through all the spit and the balloon-red face that he was giving me, was that he was saying the whistle hadn’t stopped. I had stopped before the whistle. In a football game, that was like waiting in the lunch line and then leaving it before you get your food. I managed to let out a measly “yes, sir.”

That was the first thing that football taught me, not necessarily perseverance, more like not-quitting.

We were to always address our coaches as “sir,” take care of all the gear and pads that we needed, and go 100% at practice without complaints. The ones who weren’t able to obey these rules were punished, and many of those who were punished quit. They permanently labeled themselves as “quitters” and thus fueled the fire of the coaches to make the ones that remained standing practice harder.

There was a distinct difference between hurt and injured. Hurt meant a lot of pain, and pain you could play through. Injured, however, meant unplayable.

These “requirements” for playing football taught me a lot. I didn’t know toughness until I spent hours on the field going as hard as I could. I didn’t know perseverance until after I made it through one of these practices. I didn’t know discipline until after I made it through a week of practice. I didn’t know respect until a firm handshake and a yes sir were ingrained into me as I talked to coaches.

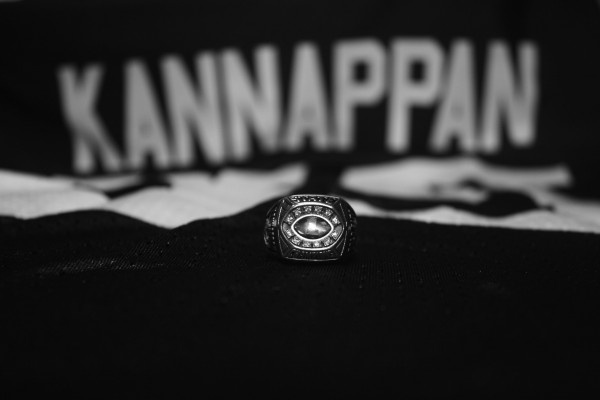

Essentially, what football taught me was how to be a man. After 11 years of rolling around the dirt and countless hours of sweat and toil, it paid off. We won the 2010 CIF State Championship. In Pop Warner, we went to two super bowls, but never took home a title. I didn’t know what the state championship meant to me until the summer before my senior year.

This was it. This was as far as my football career was going to take me. I didn’t have the size or the speed for the next level. I spent the previous year trying to make Kevin Anderson (’11) better by being his blocking dummy, and believe me, it wasn’t fun. I figured that this year, it was my turn to get better in other things. That is why I chose to leave football.

I will never forget what football has done for me, football taught me life and how to suck it up and get through it.