“The race starts at about five in the morning,” ultra-marathon runner Stan Jensen said of his 1999 experience running the Leadville 100-mile ultramarathon. “There are around 600 people.”

He put on snug socks, laced up his shoes, and pinned on his bib. Filled the water bottles, had a cup of coffee and a bagel, and took care of all the basics.

“There was a countdown clock, and we were watching it, and when it got to zero, a gun went off and 600 of us started running through the streets of Leadville,” he said.

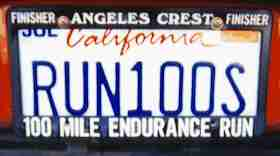

Ultramarathon running is the sport of competing in races longer than the normal marathon distance of 26.2 miles, and encompasses races anywhere from 50 km to 2989 km. Races can also be measured by duration, such as in the 24, 48, or 72-hour run, or fall into the category of Self-Transcendence runs, in which a runner runs around a certain track for a specified duration or to satisfy a distance requirement (the title of the longest certified footrace goes to the Self-Transcendence 3,100 mile race, in which runners complete 5,649 laps of a single 0.5488 mile course in Queens, N.Y. within 52 days).

“It’s kind of like taking the marathon to the next level,” New York-based ultramarathon runner Christopher Baker said. “After I did a bunch of marathons it became a sort of quest to see what I could do.”

The culture built around ultramarathon running has clearly grown from its early days in Northern Mexico, where the Tarahumara (Rarámuri) Native Americans ran and still run great distances in the hills and rocky cliffs in thin, leather sandals.

But, even with highly specialized shoes and advanced medicine, the challenge remains the same.

“In the first mile, it’s like, ‘Oh my gosh, this feels terrible; how am I supposed to go another 90 miles?’” Gillian Robinson, ultramarathon runner and co-owner of the ZombieRunner running store in Palo Alto, said.

For many, marathon distance is an ultimate goal, and for others, an impossibility, but these ‘ultras’ stretch the boundaries. The 100-miler would be the equivalent of running from Palo Alto to Sacramento on trails and mountainous alpine segments. “Respect the distance,” reads a popular ultramarathon aphorism. Perhaps another aphorism should read “Respect the altitude.”

The Badwater Ultra, for example, begins at the lowest point in the Western Hemisphere, in Badwater, Calif., and finishes at the trailhead to the Mt. Whitney summit. Temperatures of over 125ºF accompany the 13,000 feet of vertical ascent and 4,700 of descent. The AdventureCorps, developer of the Badwater race, warns runners to “NEVER USE A GPS TO NAVIGATE IN DEATH VALLEY,” a barren desert of scare roads, and even scarcer runners.

Runners must reach certain aid stations along the course before designated times and finish the course within a set time interval. Walking is permitted, as long as one can reach an aid station in time. Generally, runners have ample time intervals to compensate for the generous yet grueling distances.

“Most 100-milers are broken up into aid stations every three to ten miles so you get a little bit of a break every once in a while with food and water,” ultramarathon runner and ZombieRunner co-owner Don Lundell said.

Hydration and nourishment become even more important as the body pushes on past its normal limits.

“It’s often called an eating and drinking event because you’re managing your hydration, you’re managing your calorie intake, [and] you’re managing blisters,” ultra-marathon runner and Mira Loma High School Principal Paul Oropallo said.

Volunteers and employees often stock up aid stations with sufficient edibles since runners can burn over 10,000 calories in a single 100-miler. Burritos, sushi and grilled cheese can only account for about half of the calorie deficit though. Sometimes excessive sweating induces hyponatremia, or low sodium in the bloodstream; runners can receive intravenous supplements for nutrient deficits after the race.

On top of internal body care, clothing must be just right for the time of day, lest one suffer from hypothermia or heatstroke. Scott Jurek, the top finisher in the 2005 and 2006 Badwater ultra, had to dip himself in buckets of ice to lower his core temperature, before it reheated from the blazing sun. Of course, in such extreme conditions, irony prevails, and clothing instead protected him from the heat

“Badwater’s very unique because it’s just so hot, [so] you have to wear long pants and a long sleeve shirt and shield yourself from the sun,” Jurek said.

For shorter races, clothes can wick moisture from the skin and prevent sweat from weighing the runner down. Some runners pack warmer clothing in their drop-bags for nighttime running and shed it when the sun rises again.

By 30 miles, hopefully a rhythm has set in. Triathalon.org writes that “staying at the same pace requires less energy than getting used to a new or fluctuating pace.” Runners also want to barge through the metaphoric wall of physical breakdown that many marathoners experience at around 20 miles, as the body runs out of its glycogen stores in the liver and carbohydrates and sugar in the body.

From a psychological standpoint, “it’s overcoming that fatigue you feel in the muscles because the nervous system can override [that],” Jurek said.

When the so-called runners’ high isn’t enough to keep the legs going, it’s up to the brain to keep things on track.

“30 miles is the reality checkpoint with yourself because that’s close to a 50 km distance,” Robinson said. “You want to feel really good at that point. With 100-milers you’re focusing on pacing down making sure that you’re not too far ahead of schedule until later. If you’ve hit that same point as you would in a 30 mile race, that’s a problem.”

For a runner, the next 20 miles ideally prove uneventful. The Leadville Ultra serves its runners meadows with streams filled with snowmelt and the mountainous Hope Pass, and athletes have to cope. Some break from the pressure; others rise to the task. Jensen falls in the latter category, and celebrated the view from the top of Hope Pass.

“I looked [back] and 48 miles ahead was the town of Leadville where I had started and where I was going to finish,” he said. “And it wasn’t like thinking how much time I have left but my god, way out in the distance, 48 miles away, I’m going to be there tomorrow at 11 a.m. I don’t know how, but I’m going to be there.”

_________________________________________________________________

“The next point where you’re checking with yourself and seeing how things are is the 50 mile point because it’s the halfway point and usually you’re heading toward darkness,” Robinson said.

Now, runners meet the psychological challenges of running through the night despite exhaustion. Slow runners can be out for even two nights without sleep, and sleep deprivation concerns both race officials and runners.

“The transition into nighttime can be interesting because you’re moving into a different section of the race,” she said. “People act different, people get sleepy, [and] people can start hallucinating. It’s harder to see where you’re going and as you get later at night the body wants to rest, so you’re fighting the body.”

With darkness telling the body to rest, the mental aspect of ultramarathon running deserves much attention, and to some, even more so than that of the physical aspect.

“The mental aspect of ultramarathon running is 95 percent a game because you’re out there [and] you’re telling [yourself] that I’m going to run for half the day,” New York-based runner Baker explained. “Most people would say that’s impossible, but anyone who’s in some physical conditional can really do it with the proper knowledge and background.”

Jurek takes it further. Just like in any other sport, athletes talk about experiencing ‘the zone’, in which a basketball hoop seemingly gets larger and larger or the pool gets shorter and shorter. Getting past the runners’ high to an exquisite, yet “altered” state of consciousness is easy with the ultra-distances. As the body shuts down, the brain takes control.

“You have to get to the point where your physical body has been broken down or you have to deal with a very tough problem physically,” he said, “Mentally you have to figure out ‘how am I going to get through this, how am I going to keep pressing forward?’ A lot of people have been trying to explain it for years and have been looking at artists or people who are in a meditative state, and it’s like becoming immersed in the present moment, where nothing else matters.”

This meditative zone lures many runners into long, physical workouts, and as a result runners sometimes neglect building mental endurance along with physical endurance. Jensen warns against solely relying on one’s physical capabilities.

“You can do as much training as possible but when you’re out alone, your brain can easily talk you into quitting,” he said.

For some, mental training includes spontaneously doubling the length of a run to build up mental endurance. For others, the mental aspect includes strategizing. Running a course before competition day gives competitors an edge because they know when to push and when to relax. They can also plan what to put into their drop-bags at certain points or what to eat and drink at certain aid stations.

Pacing becomes ever more important when runners still have 30 or 40 miles to go. Strategic naps and calorie intake can sometimes rescue a runner from dropping out. Runners sometimes use pacers to keep themselves awake, on the trail, and away from rattlesnakes and scorpions.

But by the wee hours of the morning, aid and planning only go so far. Many consider the midnight to 6 a.m. section the toughest part of the race. When the dark arrives, the body starts to shut down, in preparation for sleep. Metabolism decreases, and therefore maintaining speed turns difficult. In the hilly or dense patches of trails, decreased visibility becomes a problem.

“It can be a very surreal experience, running at night… because you now all of a sudden need to be in tune with your environment,” Jurek said. “Your hearing and your sense of proprioception and knowing how the trail feels via what happens at your foot and ankle versus what happens just at your eyesight” are the only ways to stay on the trail.

Blackness removes one’s spotting ability, when one looks at his/her surrounding to determine orientation, and so the line between wakefulness and the aforementioned meditative state is further removed. For Robinson, at least, the dark can also provide a canvas for the imagination, as many runners can experience hallucinations from sleep deprivation.

“There was one race [out in Arizona] where I saw a bench full of people dressed in clothing from the 1800’s,” Robinson said. “The cactus looked like a cowboy and there was the big picture man, and there was weird stuff in the desert. I’ve seen dragons, I’ve seen gnomes that stop and wave and say hello… and Gucci bags in the streets.”

_________________________________________________________________

The dawn of a new day brings new beginnings.

“When the sun starts and finally comes up it’s literally and figuratively a new day,” Robinson said. “You can be completely revived.”

From the swampy darkness arises a new spirit for running; conversations flow between running partners, the sunrise provides for pretty pictures, and bitter, hard-worn faces give way to bright, shiny smiles.

This scene is not reserved solely for ultramarathon runners, though. Mountaineers, orienteers, and long-distance runners all join ultramarathon running in a family of sports in which athletes travel great distances along the lines of 30-100 miles on foot (and sometimes even more). For these distance athletes, running a marathon would be considered a discipline focused on speed, like a 100-meter dash, while running an ultramarathon would be considered a long-distance event, like a cross-country race. Not all long-distance runners participate in ultramarathons, though.

At Palo Alto High School, English Instructional Supervisor, teacher, and long-distance runner Shirley Tokheim sometimes travels up to 30 or 40 miles in a single run. Although she hasn’t completed a 100-miler yet, she thinks of long-distance running as ultramarathon training.

“A lot of people think of the 100 km race (62 mi) as training for a 100-miler,” she said.

These long-distance runners often run for pleasure and don’t compete in ultramarathons for various reasons, including schedule conflicts or training difficulties, but still share much of the same mentality that ultramarathon runners have.

“The endurance running has given me perspective on accomplishing anything,” Tokheim said. “It’s a metaphor for how to do life; that’s how it’s worked for me and you need to have the goal.”

Goals for ultramarathon runners range from simply finishing a race to setting new records, but these athletes share a bond from the great distances they’ve traveled together.

“People often like to train together,” Leadville runner Jensen said. “It’s very much ‘we’re all in this together.’”

Jensen sometimes runs with members of the Palo Alto Run Club, which on its website states that it aims to “participate in, support, and produce both non-competitive and competitive group running events in [the] Palo Alto Area and nearby communities.”

Nonetheless, Robinson cites an individual’s drive and mental perseverance as the reason why some ultramarathon runners are successful and others aren’t.

“At the end of it all it’s that you want to finish that makes you finish, and realizing that afterwards can really change a person,” Robinson said. “The first 100[-miler] I did, I cried.”

In broad daylight, Jensen crossed the finish line. He had been running for 28 hours and 17 minutes.

“If you start thinking about that, it’s crazy,” Jensen said.

It’s Sunday.