Paly green. Olympic gold. Fade to black.

The story of wrestlers Dave (’77) and Mark (’78) Schultz, their success at Paly and beyond, and the tragedy that cut one of their lives short.

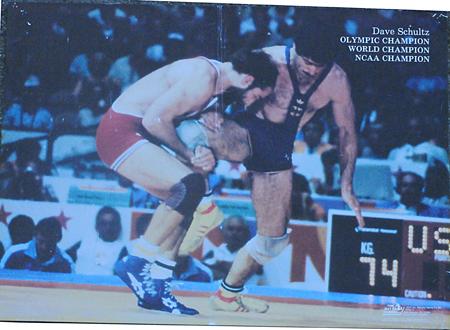

Former Paly wrestler Dave Schultz (’77) won NCAA, world and Olympic championships.

February 22, 2010

With the Vancouver Olympics in full swing, fans around the world watch the world’s best athletes and pick their heroes. They dream of what it would be like to stand on the podium with a medal around their own neck. But by the time the next Olympic games roll around, many of these heroes are forgotten. The gold fades with time and these great athletes fall into obscurity.

Around campus at Palo Alto High School, not many people recognize the last name Schultz. But wrestlers do. They recognize the name of the “Paly wrestling legends” who went to Paly in the 70s. They wrestle under pictures of the two. But other than that, Dave and Mark Schultz are dusty heroes.

DAVE (’77) AND MARK (’78) won nearly every title an amateur wrestler could. They both won California state championships as Paly students, and went on to take NCAA, world and Olympic titles as well. Wherever they were, Dave and Mark were always looking ahead toward the next step. In 1996, Dave was training for the Olympics in Atlanta with hopes of taking home a second gold medal when he was shot and killed on a wrestling facility in Pennsylvania by a wrestling patron.

Ever since, Mark and the wrestling world have been looking back, remembering the loss of Dave, but also the legacy he left behind.

THE STORY starts in Palo Alto.

The Schultz family lived in a blue house with white trimming on a quiet street winding down the Palo Alto Creek. A large redwood tree stands in front of the house and the backyard hosts two palm trees. This is where the Schultz brothers lived with their father.

Dave and Mark’s father, Phil Schultz, raised the brothers in Palo Alto while their mother, Dorothy St. Germain, lived in Oregon.

From the beginning, Dave and Mark made one point very clear – wrestling was their thing.

They found the Paly wrestling room by themselves. The room that Dave and Mark knew as the wrestling room is now Paly’s weight room.

Thirty years ago, this room seemed more spacious. Instead of carelessly discarded free weights, wrestling mats covered the floor.

Today, the room is grimy and cramped. The small room standing in the shadow of the gym seems far too small for all the weights, machines and constant flow of athletes. Mark and Dave spent hours upon hours in this room, sweating and working toward their next match or tournament.

Phil, a professor at Menlo College, went to competitions to see his sons compete, but never pushed them to be great. They did that on their own.

Dave was the technician and Mark the physical grappler. But there was one thing that seemed to run in the Schultz blood: a love of winning and a ferocity on the mat.

As middle school boys, they trained with high school and college wrestlers.

Even as a freshman at Jordan Junior High (as it was called then) in Palo Alto, Dave knew the weight room’s space well. The chubby and even unathletic-looking ninth grader was still a year away from becoming a Viking, but he practiced with the Paly team under then-coach Ed Hart, soaking up every piece of information along the way.

Current Gunn High School wrestling coach and athletic director Chris Horpel first met Dave when Horpel was already an NCAA All-American wrestler for Stanford. The 14-year-old Dave walked across El Camino from Paly, asking the 21-year-old Horpel to wrestle with him. Horpel agreed, hoping to get rid of the middle schooler after a few sessions. To his surprise, Dave kept coming back.

“At first it was like wrestling a puppy dog, and I didn’t think he was going to amount to anything,” Horpel said. “But within a year, he had placed fourth in CCS, and also fourth in state.”

Within just a few years of picking up the sport, wrestling completely consumed Dave’s life.

“He lived, breathed, drank, ate wrestling,” Hart said. “He walked around campus with his wrestling shoes tied around his neck – literally. He didn’t even bother to get his driver’s license or anything when he turned 16 because he didn’t have time to take the class or anything. He wanted to just think about wrestling.”

Dave’s tunnel vision and an intense focus kept him committed to wrestling above all else. Hart remembers how Dave started dating a girl during his senior year and told her right off the bat that wrestling was his life, and that she had better not try to interfere.

“So, one day she says, ‘Don’t you think you’re spending a little too much time with wrestling and you should spend more with me?’ And boom, he dropped her,” Hart said.

AS A HIGHSCHOOLER, Dave competed at the world level.

Dave’s success was unexpected for most people who knew him at the time because Dave not only looked unathletic, but also did not have the ego of a great athlete. Everyone knew how seriously Dave took wrestling, but his humble attitude did not call attention to his great talent. Walking around Paly, everyone saw his wrestling shoes around his neck. They knew he had his singlet on underneath his clothes. But only some of his classmates actually saw him on the mat, when he put on his uniform and transformed into a world class wrestler.

“[Dave] walked around like he was just another high school kid,” Paly teammate Jeff Newman (’78), who wrestled at 165 pounds, said. Newman, 50, is now a chief financial officer for a real estate firm and lives in Pasadena, Calif.

“Dave was like Clark Kent going into a phone booth,” Newman said. “He would get on the mat and dominate, and walked off like an old man that could not move very fast.”

Dave studied the sport, analyzing techniques and breaking down each move. To Dave, wrestling was like a chess match. He knew he could not always overpower his opponent with strength, but Dave could out-think him.

Dave began to develop a move he would later be known for – he would choke out his opponent using the crook of his arm (an illegal move) and then shake him around to emulate the other wrestler fighting back. After he pinned his opponent, Dave would quickly slap him to bring him back to consciousness. Dave usually got away with it.

With this focus, Dave broke onto the world stage even as a high school student. The older brother qualified to travel with the USA team to the Tbilisi Tournament in the Soviet Union during his senior year. Though Tbilisi is no longer in effect, it provided the world’s most challenging competition at the time, as countries, including wrestling powerhouse the Soviet Union, could enter multiple competitors.

While other high school wrestlers in California were preparing for the state championships, Dave wrestled with the world’s best and gave them a run for their money.

As the youngest on Team USA, Dave finished second at Tbilisi in 1977. Just a high school senior, he placed higher than any American on that trip to Europe. After this kind of a performance, the California state championship would be a piece of cake.

When Dave returned to Palo Alto, he had missed the league finals, and therefore could not compete in the state championship tournament. But coach Hart got all of the other coaches in the league to sign a petition so that Dave could compete. This petition, above all other aspects of the tournament, proved to be the most difficult part for Dave. He wrestled in the 165 pound weight class – higher than his usual weight – and still pinned all but one opponent. His closest match was 12-1, which he won for the state championship.

MARK SCHULTZ, just a year younger than his brother, was never far behind.

“Mark truly admired David,” their father Phil, who still lives in Palo Alto, said. “David was sort of an icon for him. I think Mark actually adored David. In some measure, Dave became Mark’s mentor and to some extent from time to time he fathered Mark because Mark didn’t listen to me. Thank God he listened to one of us.”

When Mark tagged along with Dave on one of the frequent trips to Paly in middle school, Hart wagered that Mark could learn to do a backflip in five minutes. Hart remembers Mark protesting, “No you can’t [teach me one], no way.” Nevertheless, after five minutes of routines, Mark did it. Just like that.

Mark followed Dave to many of his practices, although Mark’s wrestling career would not take off until his senior year, while Dave was in college. Mark did not even become involved in organized athletics until eighth grade despite the fact that coaches, teammates and family members describe him as a natural athlete.

Teach Mark a move and he knew it. Introduce a new sport and he dominated. Horpel compared working with Mark to programming a computer – once he knew a technique, he could implement it immediately.

Mark, after having family issues in Palo Alto during the first part of high school, moved to Oregon with their mother in his junior year. Mark started to wrestle while in Oregon, and returned to Palo Alto again for his senior year after becoming frustrated with his coach in the Beaver State. A late joiner of the sport, Mark lacked experieince, but it did not take him long to catch on.

Mark remembers coming back to Paly for his senior wrestling season after working out with the Stanford wrestling team all summer long. In practice, Mark took down Hart, who had not seen the younger of the Schultz brothers for a year, about ten times in a row.

Mark went 15-2 his senior year at Paly, winning the league, region, section and state championships at the 154 pound weight class for Paly in 1978, only a year after Dave won the same title. Mark transformed from a beginner to a state champion in just over a year.

WHILE MARK GAINED A STRONG foothold for himself in wrestling, Dave wrestled for Oklahoma State in Stillwater, Okla. on a wrestling scholarship. But it did not take long for the brothers to find one another.

“They had been training together since they were kids,” Alexander Schultz, Dave’s son who is now 23 years old and attends Foothill College, said of his father and his uncle. “They were both pretty mean on the mat. Mark’s kind of mean off the mat, my dad is nice off the mat.”

Dave transferred to UCLA for his sophomore year where his brother Mark, former Paly teammate Newman and Horpel all reunited. After a year filled with disputes in Los Angeles, however, the brothers landed together at Oklahoma University in Norman, Okla.

Living together at Oklahoma University, Mark (now in the 177 pound weight class) and Dave (at 163 pounds) continued to dominate, both winning NCAA titles in 1982. Mark also won the NCAA championships in ’81 (in the 163 pound class) and ’83 (177 pounds). More importantly, these college years were the first time the brothers had wrestled together.

“[Dave] was kinda like a father figure and a brother and a coach all rolled up into one for me,” Mark said of his older brother. “And I was kinda like his disciple.”

Dave continued to turn heads after graduating in 1982 by winning the 1983 World Championships, all the while preparing with his brother for the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles.

“Nobody was gonna beat him,” Mark said of Dave. “And he said, ‘Oh, I just work hard.’ He’s just a real humble guy.”

IN THOSE 1984 OLYMPICS, extra referees were assigned to both Dave (74 kg) and Mark’s matches. These referees closely monitored Mark, who wrestled above Dave in the 82 kilogram weight class, after Mark broke his opponent’s arm in his first match. Officials also watched Dave closely to make sure he did not choke anyone out.

The brothers came home from Los Angeles, each with a gold medal. Mark followed up his medal with two world titles, in 1985 and 1987.

Along the way, the two had make a living in a sport that had little money to go around.

High school and college offer amateur wrestlers like the Schultzes the chance to prosper while in a sheltered environment. But after college, the financial road gets rocky, and few opportunities allow wrestlers to train while eking out a living.

“There’s only one way for [amateur] wrestlers to survive in America and compete on an Olympic level, and that’s to become a coach somewhere,” Mark said.

That is just what the Schultz brothers did. After both brothers coached alongside Horpel at Stanford from 1983 to 1986, the two parted, though they both continued coaching and wrestling simultaneously.

Dave took a job as a coach for the University of Wisconsin and got married. During this three year coaching stint in Wisconsin, wife Nancy and Dave had their two children, Alexander and Danielle Schultz.

Even though Dave would continue to wrestle internationally until 1996, Mark’s amateur wrestling career ebbed out after he did not live up to his expectations in the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea. Mark continued coaching, but turned to a more aggressive style of wrestling called grappling during the 1990’s.

DAVE’S FIRST TRIP TO THE SOVIET UNION for the Tbilisi tournament in his senior year in 1977 marked the beginning of yet another special relationship that Dave Schultz shared. In the years following, Dave made many trips back to Russia. He took first place at Tblisi twice in later years, a feat never accomplished by any other American.

Dave’s passion for wrestling and his friendliness towards others stood out. Unlike many other wrestlers, Dave was not afraid to cross cultures to learn wrestling techniques. Dave connected with the Russians in unimaginable ways, given the tension from the Cold War, through one common interest: a love of wrestling.

Dave met the Russians with open arms. He studied their moves and techniques, and even learned to speak their language. He wanted to get better, but his likeability did more – it broke down barriers.

“The Russian people ended up loving Dave,” Hart said. “They just cheered for him, and they booed the Russian referees toward the end of his career because they were rooting for him more than they were for their own Russian people.”

Meanwhile, Mark had taken an assistant coaching job for the brand-new wrestling program at Villanova University in Pennsylvania.

Prior to making the move to Pennsylvania, Mark competed in the 1986 world team trial. That is where he first met John Eleuthere du Pont, the man who donated the money to start the Villanova program.

DU PONT, the heir to the Du Pont family chemical company fortune, was said to be worth over $200 million.

Born into wealth and privilege in 1938, du Pont grew up in Philadelphia. After finishing his education, du Pont tried to become a biathlete (an athlete that competes in both cross-country skiing and riflery), then tried his hand at the pentathlon and finally landed on wrestling.

Du Pont was different from most people, and was a diagnosed schizophrenic, according to The New York Times.

Schizophrenia is a mental health disorder, in which patients usually experience hallucinations and suffer paranoia.

Some accounts describe du Pont as a lunatic and a family outcast, while others describe him as a peculiar but overall well-intentioned person.

But one thing is certain: du Pont used his money to get what he wanted.

“Du Pont was just a philanthropist,” Hart said. “He would donate money and think that he was in charge because he donated money.”

“When I first met him, I thought, ‘There’s no way I’m going to coach at Villanova,'” Mark said. “Because this guy looked really screwed up. He looked like a nightmare; he had food caked on his teeth, dandruff caked on his hair, his leg was in a cast, and he was drunk. And he was just a mess.”

But with no other choice, Mark assisted at Villanova for two years. Although du Pont struck Mark as peculiar, Mark joined du Pont’s patroned wrestling team, Team Foxcatcher, while at Villanova. Mark sacrificed his uneasy feeling about du Pont for the all-inclusive training, as well as the room and board that Team Foxcatcher offered.

“We were all desperately poor because of the Olympic rules,” Mark said. “They wouldn’t allow us to make money, so we were forced into this life of poverty. [This] allowed guys like du Pont to take advantage of us.”

In a sport where fame was scarce and money scarcer, du Pont’s Team Foxcatcher offered many wrestlers a chance to concentrate on wrestling while not worrying about finances. The large, state-of-the-art facility he built on his estate attracted wrestlers from all over.

Mark left after two years, in 1989, to coach at Brigham Young University in Utah, where he would coach until 2000. At around the same time, Dave joined Team Foxcatcher and became the head coach.

In 1996, Dave had his eyes set on his next conquest: a second gold in the Atlanta Olympics.

As the Centennial Olympics in Atlanta approached in that year, Dave was still living with his wife and children on du Pont’s estate just outside of Philadelphia.

While training with Team Foxcatcher, Dave worked closely with du Pont and the two were said to have gotten along well.

Dave was ready. He was focused, and he was prepared. At age 36, Atlanta would have been Dave’s last realistic shot at reclaiming an Olympic gold, and the consensus in the wrestling community is that his chances were good.

JANUARY 26, 1996 changed everything.

It is difficult to imagine why du Pont shot and killed Dave on that cold Friday afternoon.

Paul Trautmann, the team leader of a multijuristictional SWAT Team in Pennsylvania called the Tactical Response Team, was at du Pont’s estate that day.

“Du Pont pulled into the driveway,” Trautmann said. “Dave was loading the car or something; his wife [Nancy Schultz] was standing at the door. And [du Pont] said, ‘Dave, come here,’ or something, and Dave walked over and du Pont pulled out a .44 mag and shot him several times. After he was even on the ground, he pumped a couple more rounds into him.”

After shooting Dave, du Pont locked himself in his mansion for two days. The SWAT team shut off the house’s heating system in the cold January weather, forcing du Pont to eventually emerge. Trautmann tackled du Pont to the ground and took him into custody after the two-day standoff.

Different theories have emerged about why the multi-millionaire took the wrestling great. Du Pont never offered any answers.

“To this day, he’s never said why,” Trautmann said. “There are many theories, but there has never been an actual motive that he has been disclosed to anybody. He [du Pont] wanted to be a great everything, and he never really was. But it happened and there’s no getting around it. And to this day, no one knows why. And I don’t think anybody ever will truly know.”

At the trial, du Pont’s lawyers claimed that he was insane and unable to realize what he was doing at the time, although never denying the fact that du Pont killed Dave.

As of press time, Taras Wochok, the attorney who represents du Pont, refused to speak about du Pont’s personality due to ongoing issues with du Pont’s legal situation. Additionally, repeated attempts to contact the du Pont family were unanswered.

In 1997, du Pont was found guilty but mentally ill and is serving to 13 to 30 years in prison. The 71-year-old du Pont was denied parole in 2008, reportedly for not showing remorse for the murder.

“It’s the Du Pont family – they’re known for having lots of money and gunpowder,” Trautmann said.

In a later statement, Trautmann said that when the Du Pont family first came to America, they were in the gunpowder industry.

A memorial service was held at the University of Pennsylvania and Dave’s body was cremated.

After going from Paly to the podium, Dave Schultz’s days of wrestling came to an abrupt halt, and younger brother Mark lost his teammate and brother.

THE WORD SPREAD QUICKLY throughout the wrestling community and the national media. The most common word used to describe the reaction: shock.

People who knew him could not believe it. Dave was supposed to go to the 1996 Olympics. He was supposed to win a gold medal. He was supposed to make it to the next step.

“When I heard [about the murder], it was a shock,” Tony Brewer (’75), Dave’s teammate at Paly for a year and a current Paly wrestling coach, said. “It just seemed so crazy. I heard it just like everyone else – on TV early in the morning.”

Confusion swept the wrestling community.

Horpel, Dave’s longtime coach, was checking into a motel with his Stanford wrestling team when one of his wrestlers told him that Dave Schultz was on the news. At first, Horpel thought that Dave was being profiled for the upcoming Olympics. But it did not take long for him to realize what had happened.

“I was absolutely shocked that he had been shot and killed,” Horpel said. “And as soon as they said that, I just burst into tears. It was like I had lost my best friend. Even though Dave and I were coach and athlete, we were like brothers, really. I had worked with him since he was in middle school and [had] seen him go from this pudgy little nothing to this unbelievable champion. And so, it absolutely destroyed me.”

Dave’s death meant the loss of a competitor, a teammate, a husband, a father and a son.

It also meant the loss of a big brother.

“When I had to tell Mark that David was gone, that he was killed, Mark just… he was at Brigham Young, coaching and he just went crazy,” father Phil said. “I could just hear all these file cabinets going over, he was just throwing them over. He was bereft.”

THE USA WRESTLING TEAM would go to the 1996 Atlanta Games without Dave.

Despite Dave’s death, there were Schultzes at the Olympics. Nancy and their children, Alexander and Danielle, went to be with the people who loved Dave. The wrestling community, still navigating the aftershocks of Dave’s death, pulled together around the Schultz family. The American wrestling team came home with eight gold medals that year, one more than the Soviets took. The USA wrestling team honored Dave’s memory by wearing black patches and T-shirts with Dave’s picture.

Dave seemed to touch everyone who knew him. Some looked up to him for his medals, trophies and titles. Some admired his boyish love of wrestling. Some remembered his openness and sincerity. Everyone he met seems to remember him.

“For some reason Dave’s death affected me more than almost anything I’ve ever had to go through,” Horpel said. “Dave added something that few gave to the sport of wrestling. To have loved him and lost him is one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to go through.”

But Dave even left a long-lasting impression on Brewer, the current wrestling coach at Paly (and former professional baseball player), though the two had only wrestled together for about a year.

“He was that type of person; you weren’t going to forget him,” Brewer said. “If you spent any amount of time with him, [you would know that] he was different from most kids. I loved baseball, but not to the extent that he loved wrestling. And you don’t see a lot of kids like that, that sacrifice so much and are willing to do whatever it [takes] to succeed. That’s, of course, going to stick in your mind.”

Although the initial shock of Dave’s death did pass, the loss has had a presence in Mark’s life ever since.

“We didn’t have much stability in our lives because our parents were divorced and we were going back and forth,” Mark said. “Dave was really the only constant in my life. When I lost him… I have never gotten over it.”

Mark lost more than his brother that day. In one moment his mentor, teammate and inspiration was also lost.

“David’s loss was so powerful, especially on Mark, that it’s taken Mark years to just overcome it,” Phil said. “And I’m not sure he’s completely overcome it. It’s just been very difficult for him. They were sort of just joined at the hip. They did a lot together – wrestled together, ate together, caroused together.”

All this time spent together bonded the brothers in a unique way. Phil remembers how the brothers looked out for each other as their lives always seemed to intertwine.

“They really cared about each other,” Phil said. “It was a wonderful bond. They just loved each other. Deeply.”

The tragedy of Dave’s death has been particularly difficult to overcome for everyone who knew him because he had formed so many special relationships. But for Mark, the best way to get through it was to go back to wrestling.

Mark, still at BYU when Dave was murdered, was training Dave Benito for the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC IX). Just days before the fight, Mark broke Benito’s hand, decided to compete against former UFC finalist Gary “Big Daddy” Goodridge and won UFC IX (his only ever UFC appearance) – all just four months after Dave was killed.

But Dave was not far from Mark, or anybody else’s, mind.

“I don’t know if you ever really get past it, but you do get through it, per diem,” Phil said. “And time does help.”

After Dave’s death, Nancy formed the Dave Schultz Wrestling Club in honor of her husband. Today, every college in California represents this club as a part of USA Wrestling in a show of respect and remembrance for the great wrestler. On top of this, an annual tournament, the Dave Schultz Memorial International Championships, is held in Colorado Springs.

But a tournament is not what Dave is remembered for. Dave Schultz is remembered as a genuine student of wrestling. He is remembered as the big brother and mentor of UFC, world and Olympic champion Mark Schultz. He is remembered as a champion.

The Schultz brothers were always looking ahead. This is precisely what made former Paly wrestlers Dave and Mark Schultz legends. In whatever they did, the Schultz brothers were always looking forward, preparing for the next pin, the next round, the next tournament and the next title.

“If there’s a reason besides my own selfish one to get him back,” Phil said, “it would be so he could be with his brother, and his brother could be with him.”

Additional reporting by Skylar Dorosin.

Editor’s Note: The original story in the print edition of The Viking contained several grammatical errors. Additionally, a mistake was made in the publishing process and the final quote from Phil Schultz was not included in the print version. The Viking regrets these errors, and this online version reflects these changes.

Update: John E. du Pont died on Thursday Dec. 9, 2010, at Laurel Highlands. He was 72. For more information, read the New York Times article on du Pont’s death.