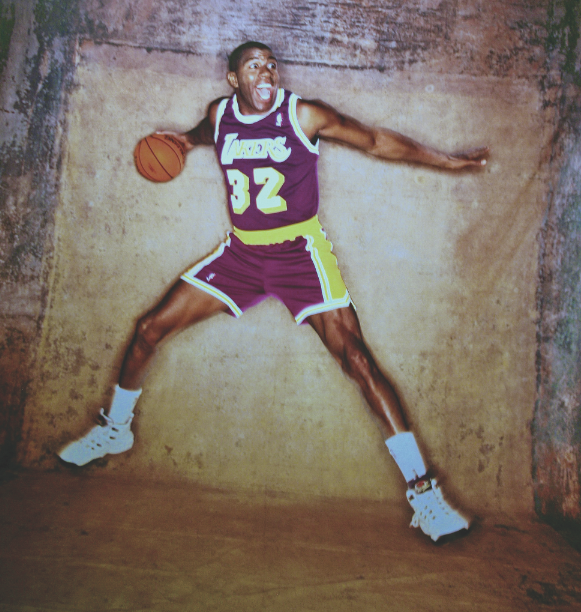

The crowd rises to its feet as a purple 32 flashes past the scorer’s table. On January 30, 1996, Earvin “Magic” Johnson makes his reappearing act with nine minutes and 39 seconds remaining in the first quarter. After missing his first shot, Magic makes an assist for a three, sinks a right-handed runner, and then posts up for a left-handed hook. Los Angeles Lakers lead by 11. With four minutes left in the first quarter, Magic pump-fakes a pass past Golden State Warrior Latrell Spreewell for an easy lay-up. In 27 minutes, Magic scores 19 points, with 10 assists and eight rebounds, leading the Lakers to a 128-118 victory over the Warriors. As the game ends with the ball in his hands, he pumps his fist and flashes a 100-watt smile. The Magic is back.

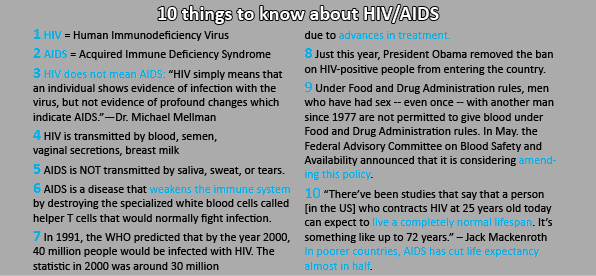

He may have been five years older and 30 pounds heavier, but the Magic who entered the game in January of 1996 played with the same heart as the Magic who left it on Nov. 7th, 1991. Only five years earlier, Earvin “Magic” Johnson announced his immediate retirement from the Los Angeles Lakers after contracting HIV (see sidebar), through unprotected sex with women. With little information and little understanding about HIV, many feared for Magic’s life, let alone his career. So, Magic did what no one expected when he took the court against the Warriors; he was living with HIV, not dying of AIDS.

“You can give athletes as many statistics as you want,” Phil Taylor of Sports Illustrated said in a recent interview with The Viking, “but it wouldn’t have the same effect as seeing Magic Johnson healthy and strong, as they see him now. That’s the proof. Magic’s not only surviving, but he’s thriving.”

Aids: The Big Picture

With the exception of in high profile cases like Magic Johnson’s, the subject of HIV does not come up very often in the world of sports, but it should. Magic made his announcement in the early 90’s when many students at Palo Alto High School were just beginning their lives. As we grew up, so did the world’s knowledge about HIV prevention and treatment. As Palo Altans, we still thought that AIDS was remote. Magic showed us that HIV was here, in our arenas and courts.

HIV/AIDS affects men and women, gay and straight, San Franciscans and Africans, adults and children, drug users and athletes. HIV positive athletes today strengthen immune systems by staying active. They also help tear down stigma on and off the court by showing that AIDS is no longer a disease for “those people”; it is our disease. Those with HIV, especially athletes, face increased discrimination, raising questions about disclosure.

The Viking was also interested in how the issue of HIV would be handled in the setting of a high school athletic program like Paly’s. Over the course of eight months, The Viking held exclusive interviews with the Lakers team physician in 1991, the reporters who broke Magic’s story, and a number of athletes living and playing with HIV.

The Magic Number, 1991

Before Magic’s press conference in 1991, AIDS was someone else’s disease, a disease for gay males and drug users. AIDS was not for someone like Magic, a heterosexual National Basketball Association (NBA) superstar at the peak of his career. Suddenly, AIDS became everyone’s disease.

Magic represents the changing face of AIDS in the early 90’s, when the tipping point changed from living with HIV and dying of AIDS due to advances in antiretroviral drugs.

“People just thought that with HIV, death was imminent,” Taylor said.

Dr. Michael Mellman, the Laker’s team physician at the time, sidelined Magic when the diagnosis was made.

“We just had to get knowledge of what he had,” Dr. Mellman said. “In that era, the magic number was six months. We had to see how someone did over six months in order to start therapy. That took him out of the season.”

Newspapers and magazines began “gathering string” for obituaries. Athletes ran from the press conference crying while others remember not being able to breathe.

For the most part, they were right to be scared for Magic. Twenty years ago, the prognosis for those with HIV was grim. Few treatment options existed, and even those did not stop the progression from HIV to AIDS. Death seemed inevitable in a few months or a few years.

In an interview with The Viking in March, Roy Johnson, editor of Men’s Fitness Magazine, recounted this fear. A longtime friend of Magic’s, Roy Johnson interviewed the NBA star and detailed the story from Magic’s point of view in a special edition of Sports Illustrated.

“People didn’t know whether they could hug him,” Roy Johnson said. “They didn’t know whether they could eat next to him, they didn’t know what would happen if he breathed on them, or if they could sit in a car next to him. He faced much of the same discrimination that other people with HIV faced.”

A few NBA players, such as Karl Malone of the Utah Jazz, were outspoken about their desire for Magic to leave the league. Regardless of who said what, everyone felt that retirement was not the best option, but the only option for Magic, out of fear for his health and for their own.

“I think he still wanted to play, and he was still capable of playing,” Roy Johnson said, “But it was too much to bear thinking that every time he got cut, the entire arena might gasp.”

Away from the headlines

I was born in 1991. It was also the year of the Rodney King Riots in Los Angeles, CA, the year the U.S. warred with Iraq to end of the Gulf War, the year the Minnesota Twins battled the Atlanta Braves to win the World Series, and the year Bill Clinton campaigned against George Bush Sr. for the presidency.

Away from the headlines, millions around the world fought a losing battle against the new pandemic: AIDS.

Magic Johnson shocked the world that year with his announcement. Off-screen, the world began trying to cope with a global disease. In 1991, someone died of AIDS every eight minutes. The World Health Organization (WHO) projected that by the year 2000, 40 million people would be infected with HIV (see sidebar).

But AIDS was not an issue for me, or for Palo Alto. In 1991, the seniors that I will be graduating with were just learning to roll over. Statistics show, however, that people around me in 1991 were living with HIV. Since 1983, 2,119 people have died of AIDS in Santa Clara County, while another 2,046 are still living with AIDS.

Africa faces an entirely different reality: dying with AIDS. When I was 13, I went to Ethiopia on a trip sponsored by the Packard Foundation. I saw kids who were sick and parents who were dying. At one rural youth center, a sea of dusty blue and green uniformed children, and a hundred pairs of eyes welcomed me. Each of the children had lost a family member, a friend, or a neighbor to AIDS.

All my life, headlines had told me that AIDS was a disease for someone else. After that visit, AIDS became more personal. What I saw in Ethiopia taught me that AIDS was for women, for children, for married couples. In Sub-Saharan Africa, AIDS is largely contracted through mother-to-child transmission and unprotected heterosexual sex. According to the US Census Bureau in 2003, 12 percent of pregnant women in Ethiopia were HIV positive with little access to treatment or hope of survival.

Aids means someone else

Fast forward. Here at Palo Alto High School, graduation of the class of 2010 is a week away. AIDS is still just a red ribbon. HIV is taught among a handful of other STD’s in a Living Skills sexual education unit.

On Paly’s courts and fields, there is no policy or plan of action in place regarding student athletes who have HIV/AIDS. Paly Athletic Director Earl Hansen says he knows of no such policy. Central Coast Section (CCS) and California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) have no specific policies regarding HIV, CCS Commissioner Nancy Blaser said in an email.

In Paly athletics, AIDS still means someone else.

“I would be stunned if I found out that someone on one of my sports teams was HIV positive,” Boys’ varsity soccer forward and varsity lacrosse middie Kris Hoglund (‘12) said.

Girls’ varsity lacrosse middie and varsity basketball guard Lauren Mah (‘10) agrees.

“I would be in a daze that HIV could really hit so close to home,” Mah said.

Maybe Paly should not be so shocked. Though they may be few and far between, high school students with HIV are not unheard of.

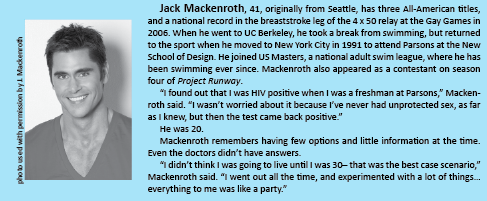

“Of course there are HIV positive athletes in high school, of course there are,” Jack Mackenroth (see profile), 41, an HIV positive swimmer in New York, said. “There are 1.1 million HIV positive people living in the United States. Nearly a quarter of them don’t know it yet.”

Current statistics suggest that Mackenroth’s assumption is correct. According to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), there were 1,392 reported cases of 13-19 year old Californians living with HIV as of September 30, 2009. Approximately half of all new adult HIV infections occur in 15-24 year olds.

“Teenagers are sexually active, and they think that they are invincible,” Mackenroth said. “You have to realize that I was only 20 when I got HIV, so I wasn’t that far out of high school.”

Who to tell? The disclosure issue

While Mackenroth is living proof that HIV can affect young athletes, many students in the Paly community cannot identify with the possibility of infection.

“I’d want to know why and how the hell he got it,” varsity wrestler Jack Sakai (‘10) said. “How many people do you know at Paly with HIV?”

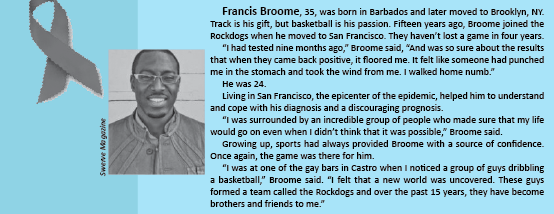

Good question. Without mandatory disclosure, HIV positive athletes face a decision about sharing their HIV status. Francis Broome (see profile), 35, an HIV positive basketball player in San Francisco, recalls that disclosure is not easy for fear of discrimination.

“It’s like coming out all over again,” Broome said. “You lose some people in the process. Your feelings can get trampled on if you don’t develop a thick coat quickly.”

While disclosure of HIV status is a gamble, being open and honest about HIV can send a powerful message.

“I can count on one hand the number of celebrities or public figures who are open about their HIV status,” Mackenroth said. As a contestant on BRAVO’s Project Runway in 2007, Mackenroth used his elevated visibility to bring the discussion of HIV and AIDS into millions of household living rooms.

“I was happy to take on the role of the HIV positive poster boy.”

Broome believes that there is far more to gain from honesty and openness when it comes to HIV and AIDS.

“I have told people for various reasons,” Broome said. “To educate, to bond, to allay fears and concerns, so they can put a face to ‘those people’, to teach, to come out of my shell, to help with my own discomfort, to show that it’s just a disease and will not cripple me from living my life.”

The debate about whether or not athletes should disclose their HIV status is far from settled. Magic went public days after he found out, while Olympic diver Greg Louganis came out in his autobiography years after a potentially threatening diving accident at the Seoul Olympics in 1988, in which he hit his head on the diving board.

When playing means blood

At Paly, administration, coaches, and athletes alike advocate full disclosure, but for different reasons.

“I don’t believe there is a law that says you have to [disclose HIV], but there should be,” Paly Athletic Director Earl Hansen said.

Hansen’s stance is largely fueled by his concern for student athletes.

“They could be a danger to anyone,” Hansen said. “I don’t know if you can keep something that serious a secret. How would you feel if you had an open wound and you were wrestling somebody and they were HIV positive but you didn’t know it? Then you caught it. How are you going to feel?”

Others in Paly’s community of student athletes echo Hansen’s opinion.

“If someone on my team had HIV, I would really want to know who it was,” varsity wrestler Joey Christopherson (‘12) said. “I would not feel comfortable wrestling someone with HIV.”

Sakai, a teammate of Christopherson’s, feels the same way.

“I’d avoid drilling with that guy altogether,” Sakai said. “In wrestling, it’s not rare to see blood being shed, even at practice.”

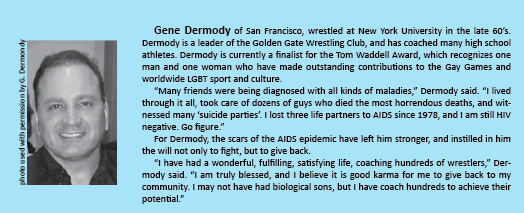

In wrestling, bloody noses, scratches, and cuts from shoes and headgear are seldom cause for alarm. Even so, Golden Gate Wrestling Club coach Gene Dermody (see profile), 61, notes that fear and misinformation still create a fog around HIV positive athletes. Over the last 30 years, Dermody has coached many HIV positive wrestlers though he himself is HIV negative.

“Homophobia is rapidly dying a quick death in this new generation,” Dermody said. “But HIV fears are still there and in many cases, warranted.”

HIV positive athletes also worry about putting their competitors at risk.

“There were the occasional ‘what if’s’ that came to my mind,” Broome said. “What if I got injured and bled during a game?”

Athletic competitions at all levels and across most sports have regulations that immediately remove athletes from the game if they draw blood. Since the AIDS virus is most commonly transmitted in athletics through blood-to-blood contact, sports with the highest risk of transmission include wresting, boxing and rugby. In other sports, such as soccer or basketball, transmission is a lot less likely. A basketball player’s risk of contracting AIDS from incidental touching is 1 in 85 million, according to the Center for Disease Control. Additionally, HIV transmission through sport poses a significantly smaller risk of infection compared to ringworm or other skin diseases.

Playing hard, playing safe

HIV positive athletes are not only concerned with the health of their competitors, but also with their own.

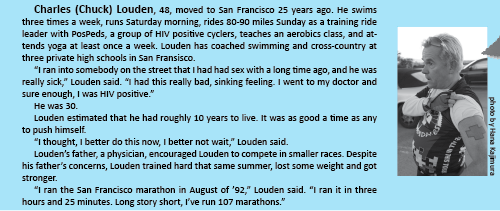

One Sunday morning in May, Chuck Louden (see profile), 48, and the PosPeds team were riding at the Russian River when it began to rain. About a quarter of the cyclists decided to pedal back to San Francisco; the rest ended their ride.

“The riding conditions are not that great,” Louden said. “I don’t want to get sick. My immune system isn’t as strong as everybody else’s. I certainly want to be a part of the game, and exercise and work out, but I’ve also got to take precautions. Today it’s raining, and it’s not worth getting sick. HIV has taught me that I’m number one. I come first.”

Despite any added risk, sports are a better option than the alternative.

“I’d rather be out peddling with my friends or running with my running group than sitting in a meeting where people are smoking cigarettes and complaining that they’re getting sick,” Louden said. “You have to stick with the winners.”

Positive Progress

Since that autumn day in 1991 when Magic stood at the podium and shook the sports world with his HIV announcement, much has changed. Protocol is now in place about injuries and blood in athletic competitions; physicians have become experts on effective treatments; and laws protect the rights of those living with HIV/AIDS. Athletes like Magic Johnson and Chuck Louden provide examples of positive approaches to living and competing with HIV.

“Fifteen to 20 years ago, people felt sorry for us,” Louden said. “I was always really clear that I did not want people feeling sorry for me. I didn’t feel sorry for myself, and I didn’t want to be an object of pity.”

HIV is not a sure death sentence for an athlete anymore; it is an obstacle that is no longer a reason to stop playing or to feel excluded.

“I’m not ashamed of having HIV,” Louden said. “Don’t get me wrong, I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy, but I’m not ashamed of it. There’s nothing wrong with me.”

Paly has also come a long way in the last 20 years. Though the school and CCS conference still lack a policy concerning HIV positive athletes, this community has raised its awareness. Attitudes are changing.

“On the field, you’re all just athletes,” Mah said. “You don’t think about who to treat differently because the biggest form of respect is challenging someone to make them stronger.”<<<