Great teams have great supporting communities that fill the bleachers. The legendary Milan High School Hoosiers played for a community that rallied around them and followed them all the way to the 1954 Indiana basketball state championship. The famed Permian High School Panthers football team of Odessa, Tex. is supported today by a community that lives to watch its team play. The Panthers are not famous for their success alone, but for the community that supports them. That is exactly what a great sports community does: it rallies around its team and provides support through wins and losses of all magnitudes

At times, East Palo Alto and Palo Alto seem worlds apart. Drive west down University Avenue after crossing the Dumbarton Bridge and head through East Palo Alto. Houses are modest; a few empty lots stand abandoned and out of place. Palm trees and taquerias dot the blocks and car radios compete for eardrums. Chain link fences surround the houses and people of all ages fill the sidewalks. Cross over Highway 101 and sit at the light for a few seconds. Head into Palo Alto and tall, shady trees line the sidewalks and two story houses suddenly appear. Stone walls and gates replace the chain-link fences. This transition alone informs any passerby that the two cities are far from ordinary neighbors.

Like the scenery, the sports communities in both cities reveal sharp contrast.

Playing sports in the city of Palo Alto is a blessing that any athlete can appreciate. Pick any sport at any level of competition and Palo Alto has it. Not only does Palo Alto have it, but the chances are the sport is well funded and organized to a tee. Coaches coach and players play. All programs work with near flawless efficiency. However, rarely does a Palo Alto team have a die-hard following. Teams struggle to carry any sense of unity beyond the limits of the playing field. When the games end, fans and players scatter to move on to the next events in their lives. The sports community in Palo Alto seems to thrive in all aspects save one: unity.

Across the San Francisquito creek an East Palo Alto community seems to have this unity concept figured out. An Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) basketball program called the Roadrunners Sports Club sits at the center of one of the strongest sports communities in the Bay Area.

Although the program is known for its highly successful basketball teams, it means more than that for the community. Kids of all ages, often times in need of role models, find guidance from the leaders of the the program.

Parents, eager to find outlets for their kids, look to the Roadrunners. While the Roadrunners provide inspiration and direction, they do more than that. Kids that enter the program are not only educated as basketball players, but also as leaders.

Roadrunners point guard and Palo Alto high School basketball and football player, Davante Adams (’11) has a foot in both worlds. Although little kids are convinced his dunks defy gravity, he is by no means in space. His mom, Pam Brown, does her best to keep him grounded. Adams spends half his time living with Brown in Palo Alto and the other half with his Dad in East Palo Alto.

Adams embodies the overlap between the two communities. While the constant transitioning may seem difficult, it has given Adams the opportunity to immerse himself in two separate sports communities. This means two sets of coaches, two sets of fans and two sources of opportunities.

When staying in Palo Alto, Adams takes advantage of his proximity to the Paly gym and the basketball courts at Stanford; while in East Palo Alto, he has a better chance of finding a good pickup game.

“Playing in EPA, people love to get a good run in,” Adams said. “Old and young.”

Growing up, Adams had his sights set on attending St. Francis High School in Mountain View, but after missing a shadow with a friend, the idea of attending St. Francis faded. Instead, he settled on Paly as his school of choice.

Having grown up playing in the Palo Alto Pop Warner football program and in the Palo Alto National Junior Basketball (NJB) league, Adams knows the community. However, Adams never feels more at home than while playing basketball for the Roadrunners. Here, Adams is free from Paly’s strict, anti-improvisation offense and rapid substitution. Here he can play loose and push the limits of his game.

“You don’t worry about all the technical things if you know that you’re not gonna be put in the doghouse,” Adams said of the Roadrunners. “If you make a mistake, it’s all good either way.”

Maybe that is why Adams takes the court for his AAU team with a different demeanor. For this squad, Adams is a leader. At Paly, his role is not always clear. Or maybe it is the community that shows up to each and every game, regardless of place and time, that gives him the ability to take his game to the next level.

“There’s always somebody comin’ to the game, whether it’s in Sacramento or wherever,” Adams said. “You have more than just the parents. You have all the kids and other peoples’ family members. We’ll pack the gym with people who aren’t even related to us.”

While crossing Highway 101 into East Menlo Park, Adams seems not to notice the change in scenery. Instead, he points out a bad driving maneuver by a Saab two cars ahead. In between discussion about how the world might be a better place if Lady Gaga did not make music, Adams talks about the promising AAU season ahead of him. This is Adams’ last year of AAU eligibility and will most likely be his best chance of getting interest from college coaches. Along with a core of veteran players including Paly players Max Schmarzo (’11) and Bill Gray (’11), the Roadrunners will look to make big statements on both the state and national levels. Guiding this effort will be the Roadrunners’ program director and coach Curtis Haggins. Having grown up in the East Palo Alto sports community playing for the Roadrunners, Haggins knows the community as well as anybody.

After driving a few blocks down Willow Road in Menlo Park, Mid-Peninsula High School appears on the right. Here, Haggins serves as Dean of students and Athletic Director.

Pinned to the wall of Haggins’ office is an article about 23-year old former Florida State University football player Myron Rolle. Along with being one of the nation’s top college safeties, Rolle performed as one of the nation’s top students. After graduating from Florida State, Rolle spent this past year at Oxford University on a Rhodes Scholarship. After a career in the National Football League, (Rolle was drafted in the sixth round in this year’s draft by the Tennesse Titans), his goal is to become a neurosurgeon. Rolle is the kind of role model that Haggins wants for kids in the Roadrunners program.

After sitting down, Adams and Haggins debate comparisons between former Ohio State University basketball player Evan Turner and Magic Johnson. Discussion soon turns to basketball on the local level. Haggins and Adams talk as if they have known each other for years. This is no illusion, as the two have known each other since Adams was an eight-year-old attending basketball clinics at the Onetta Harris Community Center, not far from Mid-Peninsula.

Unlike at Paly, Adams does not have to worry about switching coaches every year. With the Roadrunners, coaches stay with the same group of kids as they get older, which helps to build more chemistry each year the team is together.

Haggins, who recently received the Positive Coaching Alliance’s Double-Goal Coaching Award, feels that the relationships Roadrunners coaches have built with their players over the years are unlike any that can be built in Palo Alto. He believes this to be especially true for kids coming from East Palo Alto to play in Palo Alto.

“In Palo Alto, you’re gettin’ direction from somebody who doesn’t have the same struggle that you have,” Haggins said. “They don’t know that when you go home, you may not have dinner.”

While Haggins acknowledges that this is not always the case in Palo Alto, he believes that Roadrunners players are able to make stronger connections with their coaches because the coaches have fought similar battles in everyday life.

“[Coaches] have made mistakes and they’ve been down different paths, different walks of life and they have experienced things that you may go through or you may not go through, but you know they’ve been through it,” Haggins said.

Over the years, Haggins has found that this shared struggle produces a tremendous level of respect between Roadrunners coaches and their players. This ensures that coaches’ lessons do not fall on deaf ears.

“The kids are more willing to listen to somebody who has overcome obstacles than somebody who is tellin’ you somethin’ that they may have heard or saw in a movie or in a book and tryin’ to apply that to you,” Haggins said. “Experience is the best teacher.”

While Haggins believes that people face challenges in all communities, he feels that the obstacles that members of the Roadrunners have faced make the community that much stronger. In a sense, the ability to overcome adversity is what makes the Roadrunners work.

“Everybody has somethin’ in their life that they’re dealin’ with and it’s a matter of whether you’re gonna use it as a crutch or if you’re gonna use it as your motivation,” Haggins said.

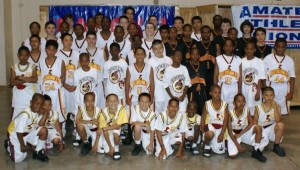

The Roadrunners seem to have taken the motivation route, as the program has seen tremendous success over the past two years. Last year, the 16 and under team took Bay Area tournaments by storm and finished the year by placing 28th at the national tournament in Orlando last July. This kind of success created a following. When the younger teams finish playing, the players and their families stay to watch the older teams in their matchups. When a Roadrunners team takes the court, members of all the other teams will be in the bleachers. Many of the younger players like to stay to watch their favorite players on the 17 and under team. Kids copy Adams’ crossover and Schmarzo’s shot. One kid even got a mohawk to look like small forward Lydell Cardwell (’11).

While fan turnout is strongest at Mid-Peninsula, the Roadrunners’ following is by no means limited to home games. In fact, Roadrunners fans often travel to neighboring cities to watch Roadrunners players play for their high school teams. One younger Roadrunners player brought his family to Paly home and away games to watch Gray, Schmarzo and Adams. It seems that no matter where a Roadrunners player plays, a Roadrunners fan is always there to watch him.

“The whole community is backin’ each other up,” Adams said. “You know that there is somebody there for you.”

The Roadrunners community is not new on the scene. Over the past few decades, Roadrunners basketball has become ingrained in the East Palo Alto and East Menlo Park community. Before the Roadrunners of today, the program was based at the Onetta Harris Community Center in East Menlo Park.

“The crazy thing about Onetta Harris is Davante’s dad played there, my uncles played there,” Haggins said. “It’s generations upon generations of people that played there and that place meant a lot to a lot of people.”

As the program developed, it became the center of Bay Area basketball culture.

“It was like the Mecca of [Bay Area] basketball,” Haggins said. “Everybody from Jason Kidd to Antonio Davis to Gary Payton played there. Anybody you can name that played basketball in the area came to Onetta Harris.”

While its basketball reputation grew, perhaps more importantly, Onetta Harris became a center for community life.

“It meant a lot to the community to have that place to go to as an outlet to watch games,” Haggins said. “It was the lifeline of the community and it is needed in a major way today.”

Since the Roadrunners program was cut from the Onetta Harris budget, Haggins has tried to restore the level of community in which he grew up. Thanks to the history of Onetta Harris, the Roadrunners are well on their way to achieving that goal.

After graduating from Woodside High School, Haggins attended Cañada Community College in Redwood City before earning a basketball scholarship at Western Illinois University. “A free education,” Haggins calls it. After college, Haggins returned to his community. For Haggins, the rationale for working in his community is simple.

“The main reason I work with the kids is a) you make lifelong friendships through sports, but b),” Haggins pauses. He talks like somebody who has been chasing this goal his entire life. “We want these kids to be good people.” Haggins’ office falls silent.

Two years ago, Bill Schmarzo brought his son Max to Mid-Peninsula to attend a tryout for a start up AAU team called the EPA Greyhounds. Both Max and Bill knew little of the program and even less of the coach. Eager for a new opportunity for summer basketball, Max tried out. A few days later, Max got a call from his new coach, Curtis Haggins, telling him that he had made the team. Two years later, Max is the starting shooting guard for the same team, now called the Roadrunners. Over those past two years, Max has become a part of the Roadrunners family.

”The kids and parents from the younger Roadrunners team always encourage me,” Max said. ”The Roadrunners community supports me on and off the court.”

Bill knows the Palo Alto sports community as well as almost anyone. Having coached all three of his kids through a variety of sports, he knows the community’s strengths and weaknesses. For strengths, Bill thinks of Palo Alto’s ability to fund and organize a variety of programs that are open to a wide range of skill levels and interests. However, he feels that coaches do not always have the kids’ best interests in mind.

”I fear that a small number of the coaches are in it for their own benefit, and not as much as for the kids’ benefits,” Bill said.

When Bill brought his son to the Roadrunners (then the Greyhounds) community, he found an environment unlike any in which his kids had played before. Both Schmarzos found something new in this program.

“The biggest difference is that the Roadrunners is more than a sports team, it is a community,” Bill said. “There is incredible community and family support.”

Beyond community support, Bill found a sense of tradition within the program.

“There is a strong sense of heritage, given the association with the Onetta Harris Community center,” Bill said. “Many of the coaches and families grew up being a part of Onetta Harris, and that sense of heritage and associated responsibility permeates everything the Roadrunners do.”

The Roadrunners community seems to be on to something. Roadrunners fans never leave bleachers empty. They do not worry about individual potential, but team progress. They hold daylong community cookouts in preparation for big games. They take struggles and mishaps and turn them into the motivation that brings everyone to the next level- together. They do everything that a truly great sports community should do. Roadrunners teams win because they owe it to their team, to their fans and to their entire community. They win because they owe it to a program that is more than just basketball. They owe it to a program that is family.