EDITOR’S NOTE: Due to the nature of this subject, this story may be difficult for some readers.

—————————————————————–

If trees could talk, the woods behind 1915 Moonlight Road would have some stories to tell. In the shadows of the white Virginia mini-mansion, the basketball court and the above-ground swimming pool, these trees saw everything that no one was supposed to see. They saw the sheds painted pitch black, windows and all. They watched on those nights in the offseason when, at around 2 a.m., two pit bulls would follow two men up a path to the biggest of the four sheds. Then the all-black door would slam shut. Leaving everyone, even the trees, in the dark.

A “hero” shut that door. A man named Michael Vick slammed it in the face of the world. At the time, Vick was the starting quarterback for the Atlanta Falcons and nothing short of an icon. He was arguably football’s most exciting player and when he hit the field, fans across America watched his every move. Vick knew this, but he also knew that in the woods behind his house in Surry County, Va., no one was looking. It was just him, his friends and his dogs.

What went on inside that shed was kept quiet. Nobody knew, nobody cared. It concerned only a few men and their stake in the money. But four years ago, USDA officers and Virginia State Police kicked that door down and the world saw everything. Investigators found a blood-stained rug dumped in the woods and blood stains on the floor and on the walls of the largest shed. By the window they found a single white dog tooth.

There it was, in the clear, for the entire world to see. Michael Vick had fought dogs. He did it for money, for respect, but most of all, he did it for fun.

This scene opened the world’s eyes to one of the largest illegal sports in the world. It also opened the world’s eyes to a breed surrounded by misunderstanding, myth and fear.

Dog fighting is a blood sport, which is a competition that involves violence against animals. Bull fighting, cockfighting and fox hunting are all included in this category. Dog fighting thrives on the human desire to observe violence, but be safe from its effects. It’s a competition with champions and trophies. There are magazines about the winners and the latest fights. Winners walk away with bragging rights and pride, but it is not like other sports.

Aside from a reputation issue, in many areas pit bulls are subject to BSL, or breed specific legislation. In 2000, the city of Denver passed a law that made it illegal to “own, possess, keep, exercise control over, maintain, harbor, transport or sell any pit bull within the city.” According to Your Dog newsletter, dog bite data kept by Denver Animal Care and Control does not match the law. In 1992, pit bulls accounted for nine reported bites within the city limits. Chow chows and their mixes accounted for 210, Labradors and their mixes accounted for 167 and poodles and their mixes accounted for 20. Over a decade later, Denver Animal Care and Control was recording new statistics for pit bulls within the city limits. Between 2005 and 2010, they impounded 3,232 pit bulls and pit bull mixes. Some of those were returned to their owners, but, without the legal right to put them up for adoption, the shelter euthanized 2,135 pit bulls.

Some California cities have also implemented BSL that requires all pit bulls to be spayed or neutered. San Francisco is one such city that recently enacted BSL.

Imagine a sport that no one wants to play. When a player wins, he is rewarded, and there is a certain level of pride. Pride in survival, pride in superiority. But when a player loses, there is death. No next time, no redemption, just overwhelming shame and no future.

The back kennels of the Peninsula Humane Society in San Mateo, Calif., are full of pit bulls. Some are big, some are small. Some bark and some just sit and watch, their heads on a swivel. Barks of all pitches combine and bounce off the walls, funneling down the aisle.

I started working with pit bulls when I learned about the Michael Vick case as a freshman. I learned about the dogs and their stories and I started to wonder what the breed was really like. Since then, I have worked with more than 100 pit bulls of all temperaments and backgrounds, and if I have learned anything, it is that each dog is an individual. Each one has its own story. Some of them I know. Some are a mystery. So, when I enter the kennel with a new dog, I need a clean slate. There is no room for stereotypes or foregone conclusions. Each dog must be handled differently.

At home, I have three pit bulls and they too come from different backgrounds. Owning pit bulls gets you two things: loyalty from your dogs and skepticism from some other people. I have to do a lot of convincing, but the bottom line is this: I work with these dogs every day and I like to think I have seen the evidence that could reverse anyone with the pit bull stereotype in their head.

As I walk through the kennels, one dog stands out from all the rest. He is a compact, muscular red pit bull. He is just like the other dogs except his face is covered with dried blood. New cuts criss-cross old scars all the way from the top of his head to the tips of his paws. His face is swollen, but he makes eye contact with me and licks my hand through the fence. A volunteer remarks that the dog was picked up a few days ago as a stray. Odds are that he lost his fight and his owners let him go. This is rare for a losing dog because most aren’t so lucky.

A pit bull is the perfect athlete: powerful, compact, explosive and determined to the point where it will stop at nothing to achieve a task.

Few people know pit bulls better than the Peninsula Humane Society’s vice president of animal care, Katie Dineen. Dineen knows their temperament, their history and everything that makes them tick. This pit bull knowledge is a given when you own six.

"They are really muscular, but not overly muscled and overly heavy," Dineen said. "They can leap three quarters of the way up a 10-foot fence to get a tennis ball...effortlessly." Photo by Brandon Dukovic. People who know the breed this well recognize pit bulls for their intelligence and their will to please. In the first half of the 20th century, pit bulls were the dog of choice for families, similar to labs today. Blind and deaf author Helen Keller chose a pit bull as her guide dog. In World War I, a pit bull named Stubby earned an assortment of medals for locating wounded soldiers. His keen sense of smell also allowed him to detect a gas attack and give a warning before the soldiers knew what was happening. Stubby was the inspiration for the United States Military K-9 Corps. Petey from “The Little Rascals” was also a pit bull. Today, if someone saw Petey, they would probably cross the street and wonder if he were involved in a fighting ring. This is the reputation that dog fighters have brought to the pit bull breed.

“They’re incredible athletes,” Dineen said. “The stamina, the muscle. [They are] really muscular, but not overly muscled and overly heavy. No big heavy heads, not a lot of extra stuff to drag around. [They] can leap three quarters of the way up a 10-foot fence to get a tennis ball…effortlessly.”

Athleticism is only half of the equation, however. Pit bulls are also known for their ability to connect with humans, a skill that Dineen believes comes from the fighting pits.

“Those who created and refined the breed selectively bred for a number of characteristics specific to dog fighting, including the ability and desire of the dog to connect with people in the most stressful situations, i.e. when they were fighting with and being hurt by another dog,” Dineen wrote in an e-mail. “Those of us who share our homes with the breed recognize the intense, joyous desire of these dogs to be right alongside their people doing whatever it is their people want to do, and it’s one of the best things about the breed.”

Unfortunately for pit bulls, these two characteristics make them the dog of choice for dog fighters. The same characteristics that respectable pit bull owners use in positive ways, dog fighters abuse and use to their advantage.

Dog fighting is a mentality, a culture and, in 48 states, a felony. The Humane Society of the United States estimates that roughly 40,000 people are involved in organized dog fighting. Although this figure is significant by itself it does not include street or backyard fighting. Beyond the cruelty of the fighting itself, dog fighting has created misconceptions that society has accepted.

Junior is a show dog owned by Dayna Pesenti, who works at the Peninsula Humane Society. Junior was the No. 1 American Staffordshire Terrier (a subcategory of the pit bull breed) in the country in 2007 and 2008. Junior also won the Best of Breed award at the Westminister Kennel Club in 2007 and 2008, in addition to the Best of Breed at the Eukanuba National Championship. Photo by Brandon Dukovic. Pit bulls are involved in dog bite incidents and maulings. What people do not realize is that all breeds are involved in these cases. Any big dog can do serious damage, but pit bulls get the headlines, and when they get headlines, people build a negative attitude toward the breed (see sidebar). The public has also created the idea that pit bulls have locking jaws and that when they bite, they will not let go. According to Dineen, this is a myth.

News about pit bulls and dog fighting has given the public the idea that every pit bull in a shelter or in a bad neighborhood is somehow tied to a fighting ring. In the Bay Area alone, there are tens of thousands of pit bulls that are family pets and nothing more.

The number of dogs involved in dog fighting are only a minuscule percentage of the pit bull population as a whole. In my time at the Peninsula Humane Society, I have seen a grand total of three dogs with scars that could indicate possible fighting backgrounds. The hundreds of other shelter dogs are just victims of foreclosures and irresponsible owners.

It is a common misconception that dog fighting is something reserved for inner-city African Americans and Latinos. In reality, white men in the Midwest run most of the largest dog fighting operations. The largest fight bust in history, according to the ASPCA, occurred in July 2009 and involved arrests of white males in eight states: Nebraska, Arkansas, Texas, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Iowa, Illinois and Missouri.

Dog fighting spans all social classes as well. Teachers and lawyers have been arrested in fight busts.

A second misconception is that pit bulls are made to fight and that they enjoy it. Pit bulls are actually even-tempered dogs that thrive on human interaction. According to the American Temperament Test Society which tests a variety of breeds in basic behavior evaluations, pit bulls pass their temperament test at rate of 84.6 percent. Miniature poodles have a 77.9 percent pass rate and collies have a 79.9 percent pass rate.

Dog fighters have attempted to turn America’s dog into America’s nightmare.

Dog fighting falls into two categories: organized fighting and street fighting. The first is run by so-called dog men. These men own dozens of dogs which they breed, test or “roll,” train and eventually fight. Dog men make a living off their dogs.

In the world of dog fighting, dog men are the professionals. They know their dogs, they understand breeding and most of all they know how to train a fighting dog. The fighting is intense, but short-lived. Training is a process. It is what the public doesn’t see on the news. This is where dog fighting gets ugly. Take one look at how a fighting dog is trained and it becomes crystal clear that everything about a vicious fighting dog is man made.

"If you cut those ears off when they’re little there’s nothing for those dogs to grab on to," Hanley said. Photo by Paige Borsos. “It’s evolutionarily against what any other dog or any other animal would do, but what’s happened over the years is that people will see a litter of puppies, pick the meanest one and then pick another group of puppies and pick that meanest one and breed those together,” Christina Hanley, lead humane investigator at the Peninsula Humane Society in San Mateo, said.

Breeding is only the beginning. Once the “mean genes” are combined in what should be an aggressive dog, the dog has to be “rolled” (tested in a practice fight) to determine if it has what it takes to fight. One humane officer estimated that 80 percent of the dogs placed in this situation don’t even “scratch.” The “scratch line” is the line drawn in each corner of the pit marking each dog’s territory. When a dog crosses that line to approach it’s opponent, it’s called scratching. Once the dog scratches, there is a good chance it may not fight its opponent.

Once these dogs pass the testing, they have to practice fighting against “bait” dogs. A bait dog can be almost anything as long as it is an easy opponent.

“They’ll pick up any random stray dog that’s not very dog aggressive and that won’t really fight back,” Hanley said. “They’ll put this dog in there who doesn’t have any aggressive tendencies towards another animal. It’s like a punching bag for a boxer.”

After practicing on bait dogs, which can also be dogs who didn’t pass the initial testing, the dog will enter a four to six week training period called “the keep.” During this period, dog men will use different training techniques to get their dog into fighting shape. Dogs will run for hours on enclosed tread mills, swim in water tanks and hang by their mouths from grip bars to strengthen jaw muscles. They will be kept separate from other dogs in order to build aggression.

Closer to the fight, some dog men, depending on the fighting ring, will do more than just train their dogs.

Some dog men cut or “crop” their dog’s ears. Breeders will occasionally do this for style, but for dog fighters it is a way to reduce blood loss in a fight.

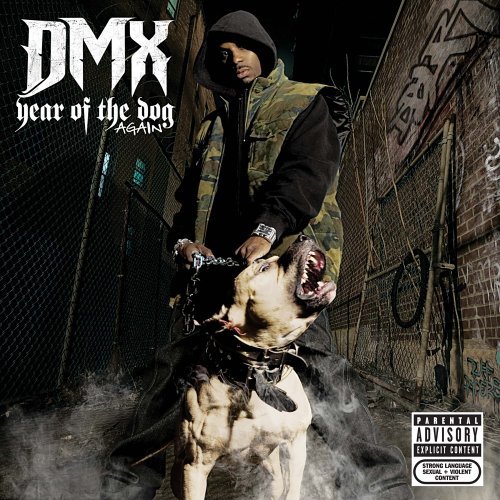

Hip-hop culture has had a major influence on the pit bull reputation. In mainstream hip-hop, pit bulls are commonplace in videos as well as in lyrics. A pit bull barking and straining against a leash shows toughness and intimidation, and the culture has accepted this as another status symbol. Some references are more subtle than others, at least to those who aren’t familiar with dog fighting terminology. Rappers often make references to five-time champions. A champion is a fighting dog that has won three registered fights, and a grand champion is a pit bull that has won five registered fights. DMX’s album, Grand Champ, features a pit bull leashed to a chain on the album cover. In 2008, the home of DMX (Earl Simmons) was raided under suspicion of dog fighting. Police seized three pit bulls and uncovered the remains of three others. Simmons was also charged with animal cruelty in New Jersey in 2002 for neglecting 13 pit bulls. He released another album, Year of the Dog… Again, in 2006.

In the music video for Jay-Z’s single, “99 Problems,” one scene is set in the middle of a dog fight and one of the dogs is lunging towards the camera attempting to charge the dog in the opposite corner. The owners are restraining their dogs as they would prior to a fight. This is how hip-hop culture portrays pit bulls and a major reason why many people accept dog fighting simply as just a part of our culture.

“The ears are very vascular and if a dog is bitten in the ear it bleeds a lot, a lot more than you would think,” Hanley said. “That’s also something that during a fight a dog can grab on to. So if you cut those ears off when they’re little there’s nothing for those dogs to grab on to.”

While it may seem extreme, cropping is minor compared to the methods of other dog fighters.

“They’ll sharpen their teeth so that the dogs can cut in and dig deeper and cause a lot more injury with their bites,” Hanley said. “They will give them methamphetamines, cocaine. They will give them painkillers so they will keep fighting through the pain.”

By this point the dog is no longer a pit bull terrier. By this point, the dog is ready to fight.

An organized dog fight is a process. According to the Humane Society of the United States’ (HSUS) law enforcement dog fighting investigation primer, there are guidelines that most fights follow.

Two dogs, usually American Pit Bull Terriers, are brought to a secret location chosen by the person organizing the fight. Each dog is weighed, then the handlers wash their dog’s opponent to make sure drugs have not been placed in the dog’s fur to stop an opponent from biting.

The dogs are then placed in opposite corners of a 20 square foot “pit” surrounded by 3-foot high wooden walls. Handlers hold their dogs while onlookers make bets. Depending on the dogs and the people involved, bets can start as high as $10,000. Once wagers are placed, each owner lets go of his dog and the fight begins. Both dogs sprint from their corner to meet their opponent in the middle. According to the primer they rise up on their back legs, lock arms and snap at each other’s heads.

The men have the power to stop their dogs at any time.

In an organized fight, a winner is proclaimed when the opposing dog either refuses to engage or is physically incapable. The owners reclaim their dogs and the fight is over, at least for the people.

Street fighting is the simple version. A man will take his dog and match it up against a dog from down the block and have them fight in a backyard or in an abandoned building. It could be fueled by a gang rivalry, money or simply entertainment.

One of Hanley’s responsibilities is dealing with dog fighting cases in San Mateo County. In her experience, Hanley has noticed a pattern in the dog fighters in the area.

“In our area typically what we’ll see is a gang member,” said Hanley “Male 15-35, [who] wants to appear very, very tough. [He] doesn’t know a lot about his dog, probably doesn’t take very good care of his dog. It’s more of a status symbol. ‘I’m really tough. I have guns I have drugs and I have this pit bull.’”

This human desire to appear intimidating is a major contributor to society’s perception of pit bulls.

Dog fighting in the Bay Area, however, is extremely rare.

“The more common thing we see around here is street fighting,” Hanley said. “You have a gangster who has a dog who wants to look tough and walks down the street with it and says ‘you wanna fight?’ and they’ll fight those dogs. Street fighting is much more common because all you have to do is get your hands on a dog.”

Unlike the world of high level organized dog fighting, street fighting often occurs in residential neighborhoods. In neighborhoods where street fighting is more visible, it can be accepted as simply another part of the culture that is passed down to the youth.

“Kids see older guys around them doing this and they want to do it,” Hanley said “It’s not illegal to have a vicious pit bull. You can’t walk around with a gun showing, but you can have your vicious pit bull.”

This is how dog fighting stays alive. People who are removed from the culture shun it, but people who grow up around it often accept it and think nothing of it. There are exceptions, however. Some choose a different path.

I know Donte Powell because of Smoka, his pit bull. Smoka plays with my dogs off-leash at the Jordan Middle School field on a regular basis. Powell is a straightforward guy. He talks with his arms crossed and looks you directly in the eye to emphasize a point.

Growing up in Kansas City, Mo., Powell always hung out with the older kids. They were his friends and his connections. Hanging out with the older kids always worked well for Powell, until one day it took him too far.

Growing up in Kansas City, Mo., Powell always hung out with the older kids. They were his friends and his connections. Hanging out with the older kids always worked well for Powell, until one day it took him too far.

When he was 14, one of his friends brought him to an abandoned warehouse to see a dog fight. Powell’s friend had seen fights before and for him it was nothing out of the ordinary. Powell, however, had a different reaction.

“I broke down and started crying when I saw it,” Powell said. “It’s bad. Watching a dog’s throat get ripped out. Some dogs lose their legs. [They] can’t bark. It’s crazy.”

After seeing the fight, Powell decided that he would take a different route than his friends. He decided to take care of his dogs and have a positive influence on them. Powell realized that he had an opportunity to raise his dogs to be good pets. Knowing the pit bull breed, he knew that he had to be a strong leader. If he could do that, his dogs would follow his lead.

“You can get any dog [to be] mean, but if you train a dog well, feed a dog well, the dog will be yours,” Powell said. “If you turn, your dog is gonna turn, because your dog feeds off your energy.”

At one point in his life, Powell estimates that he had 27 pit bulls. He was a pit bull breeder, but his business was shut down when neighbors complained and animal control seized most of his dogs. Today, living in Palo Alto, Powell is down to one: Smoka.

At the Jordan field, Powell watches as Smoka lumbers from dog to dog looking for a match up. This not in the pit, it is at a middle school field and it is for fun. Smoka sizes up an opponent, throws a playful jab with her paw, then flops on her back and kicks at the other dog half-heartedly.

This scene is far from what Powell grew up watching, but in his opinion, this is how it should be. Powell believes that the pit bull stereotype is hyped up and that it only applies to a select few dogs. He laughs when he compares Smoka to society’s view of pit bulls.

“I couldn’t see it,” Powell said. “I see her barking at somebody because they won’t pet her, but other than that, she doesn’t bark for anything.”

Powell laughs while watching Smoka, but his tone shifts when talking about the motivation behind dog fighting.

“If you have a dog that’s gonna tear up everybody’s dog, then you’re on top,” Powell said. “Everybody is gonna want a [puppy] from that dog.”

Powell sees this mentality and he tries to understand it, but no matter the motivation, the reasoning behind fighting dogs is backwards. Powell believes that dogs have a special place beside humans, and to rob a dog of that place and put it in a fighting pit is a serious problem.

Michael Vick saw his first dog fight when he was eight. In the Ridley Circle Homes Housing Project in Newport News, Va., where Vick grew up, older kids used to fight dogs in the courtyards in between the buildings. In Vick’s area, dog fighting was more common. When he had the means to support a dog fighting operation, he did it.

For some people, Vick is only a product of his environment. For Sports Illustrated senior editor Jim Gorant, this is not an excuse.

“Bad Newz Kennels (the reference to Newport News used by Vick to disguise his dog fighting ring as a boarding and breeding operation) was built on a rural 15-acre plot of land and these dogs were chained up deep in the woods and there were four sheds that were painted black,” Gorant said in an interview with The Viking. “Fights were held at two o’clock in the morning and there were a lot of rules about secrecy and how to get there. You’re not doing all of those things if you don’t know you’re doing something wrong.”

Gorant knows the Vick dogs’ history. His article, “The Good News out of Bad Newz Kennels,” was the cover story for the Dec. 29, 2008 edition of Sports Illustrated. In that story and in his book, The Lost Dogs, Gorant told the survival story of the confiscated Vick dogs.

Originally doomed to euthanasia after being labeled as some of the most vicious dogs in America by the HSUS and PETA, a team of pit bull advocates submitted a proposal for evaluating the dogs as individuals. To the surprise of the world, the evaluations showed that the Vick dogs were just dogs. Not killing machines, just a bunch of dogs with bad backgrounds.

Forty-seven of the 51 dogs taken from 1915 Moonlight Road made it to either to a home or to a rehabilitation sanctuary. One dog, Johnny Justice, participated in a program at a nearby Burlingame library serving as a one-dog audience for kids who struggle with reading aloud. To Gorant, the story of these dogs is a testament to the pit bull breed and the ultimate proof that pit bulls are not made to fight.

“Here you have pit bulls bred and raised by people with the sole intention of getting into a fight, and the success rate of making that happen is not terribly high,” Gorant said. “This case undermines what they call breed ideology, which is the equivalent of racism in human terms. You can’t judge a dog based off a breed.”

When Michael Vick’s dogs lost, they faced a different fate than the pit bull at the shelter in San Mateo. Before entering his dogs in an organized fight, Vick would test them to see if they had what it takes. He wanted to see if they were “game,” or willing to fight. This is rolling, and in some cases it determines whether or not a dog will see another day.

According to Gorant’s The Lost Dogs, two dogs of about the same size would be unchained from the car axles that lay buried deeper in the woods. Vick or one of his friends would lead the dog up a path and into the clearing where the black sheds stood. On the second floor of the largest shed the men would place the two dogs on opposite ends of the pit. The men in attendance would then clap and yell at the dogs in an attempt to spark aggression. If the dogs did not react, the men would grab them by the muzzle and push them back to the edge of the mat repeatedly. If the dogs still refused to react, they would be held just out of reach of one another forcing a stare down. Naturally, the dogs would become frustrated and the men would release them. The fight would last only a few minutes then the men would intervene.

According to Gorant’s The Lost Dogs, two dogs of about the same size would be unchained from the car axles that lay buried deeper in the woods. Vick or one of his friends would lead the dog up a path and into the clearing where the black sheds stood. On the second floor of the largest shed the men would place the two dogs on opposite ends of the pit. The men in attendance would then clap and yell at the dogs in an attempt to spark aggression. If the dogs did not react, the men would grab them by the muzzle and push them back to the edge of the mat repeatedly. If the dogs still refused to react, they would be held just out of reach of one another forcing a stare down. Naturally, the dogs would become frustrated and the men would release them. The fight would last only a few minutes then the men would intervene.

For Vick and his friends, getting these dogs to fight took effort.

Vick and his friends quickly judged the dogs who did not fight well or refused to fight at all and killed them on the spot. Some were shot and some were hanged from the trees on the edge of the clearing, some were held by their hind legs while one of the men forced the dog’s head into a bucket of water until the dog drowned. Some dogs were slammed into the ground until they died.

Dogs who fought aggressively were given food and water. Dogs aren’t stupid, they know what they have to do to survive.

Nobody knows for certain how many dogs Vick killed. He ran his operation for six years, so one can imagine how many dogs didn’t fight well enough over that time span. Vick had the money to run his operation, but he was clueless when it came to being a dog man.

“He took a street fighting mentality and tried to apply it to a large-scale dog fighting operation,” Hanley said. “None of his dogs ever won because he was still thinking like a street fighter, breeding a ton of dogs. None of them would fight so he killed them all. A lot of more high dollar dog fighting operations thought he was a complete joke and an amateur.”

While the Vick case was surrounded by negativity, a few good things did come out of it. One was that 47 dogs from a fight bust were placed in sanctuaries or adopted. Another was a new perspective. The Vick dogs were seen as victims and not as evidence. In previous fight busts the dogs were destroyed with rest of the evidence once the case was closed. In this case, each dog was evaluated on an individual basis.

In Gorant’s opinion, this case may work in pit bulls’ favor.

“Michael Vick may be the best thing that ever happened to pit bulls, because he certainly isn’t the only one out there that’s doing this,” Gorant said. “He is just the tip of the iceberg. But at the same time, what he did just shined this huge light on it, and we’re much more aware of it. Law enforcement has changed their perspective [and] now they prosecute much more of these cases.”

On a greater level, the public watched as pit bulls that were supposed to be vicious became family pets and even therapy dogs. Slowly, the public opened up to the idea that maybe pit bulls are misunderstood. Maybe they are good dogs.

Sixteen of the Vick dogs came to the Bay Area through a pit bull advocacy organization called BAD RAP (Bay Area Doglovers Responsible About Pitbulls). BAD RAP declined to be included in this story.

Donte Powell saw his first dog fight when he was 14. Unlike his friends, however, he chose to treat his dogs well and be an advocate for the breed. He and his dog, Smoka, live in Palo Alto. Photo by Brandon Dukovic. People look at dog fighting and understand the cruelty, but struggle to make it a priority in a greater context. When Sports Illustrated published Gorant’s story, he received overwhelmingly positive feedback, but there was one idea that left him thinking. Some people wondered why the public should care because after all, “They’re just dogs.”Gorant, however, has a different perspective.

“How you treat the weakest of all among you, or the least able to defend themselves, is an indicator of what your values are and whether or not there is compassion and a larger sense of caring within your society,” Gorant said. “You may not think you care and you may not think it matters, but on some level it does.”

In the back kennels at the Peninsula Humane Society, a chihuahua starts barking. The small dog is looking through a gap between the fence and the cement wall that divides each kennel. He is scratching desperately at the wall, growling and barking at the scarred red pit bull who is standing on the other side. The pit bull takes one look at the chihuahua, stares for a second as if trying to read his upstart neighbor, then turns, and trots to meet me at the fence, tail wagging. He has no will to fight, no drive to kill, just the desire to meet a new person, just the motivation to be a pit bull. So, for once in his life, he does what is natural: He chooses to greet me instead of turning on the small dog. This is a true pit bull.

Sixteen miles from San Mateo, Donte Powell looks out over the field and pauses. He takes a second to think about dogs. He takes a second to think about what happens when humans abuse power and what happens when instead we use it correctly. This is the difference between the scarred red pit bull behind the San Mateo shelter fence and Smoka, who Donte watches as she runs and plays with other dogs.

“Dogs are loyal,” Powell said. “If we don’t care about our dogs, how can we care about ourselves?”

Author’s Note: The best thing people can do to help pit bulls is educate themselves on the breed as a whole. Sites like badrap.org and pbrc.net provide great background information and history. If you are interested in adopting a pit bull, visit your local shelter and ask for the pit bulls up for adoption. If you are on the Peninsula, the Peninsula Humane Society always has a handful of great pit bulls up for adoption. Pit bulls in shelters are not there for any fault of their own. They are no more of a risk than adopting a dog from a breeder. If anything, they are safer because they have passed the temperament tests administered by the shelter. Also, shelters will spay/neuter your dog and offer training to make sure your dog gets off to a good start. If you are interesting in adopting Queenie (the dog on the front page), contact me at althompson4@yahoo.com. Feel free to ask any questions about the breed or about the story, or simply leave a comment below.

~ Alistair Thompson