Compulsion: The Complicated Intersections of Exercise and Mental Health

Health. Fitness. Wellness. When defined by their participation in athletics, each of these athletes would certainly be considered physically fit. But lost in the mix is the question of mental wellbeing—and the intersection of physical health and mental health is far more complex than a workout routine.

May 27, 2020

In 2001’s Legally Blonde, a classic murder mystery—husband murdered, wife caught standing over the bloody dead body by the daughter and the pool boy—is cracked by an unlikely candidate: Elle Woods, Delta Nu sorority queen and lover of all things pink and strawberry-scented. From the start of her assignment to the case, Elle is suspicious that the accused—Brooke Taylor, the owner of a fitness empire and instructor of exercise classes that Elle herself attended—isn’t guilty, despite the rest of the legal team remaining adamant that her lack of alibi nearly guarantees her guilt. In her defense, Elle utters one of the most memorable quotes of the film: “I just don’t think Brooke could have done this. Exercise gives you endorphins. Endorphins make you happy. Happy people just don’t shoot their husbands… they just don’t!”

While the scene is included in the film as a way to show that Elle doesn’t yet think like a lawyer, scientifically speaking, she’s got a point (well, about the endorphins; science doesn’t yet make any claims about the effects of exercise on homicidal tendencies). Exercise has long been seen as a potential therapeutic treatment in the public eye, and by the medical sector as well. According to the Washington Post, while “exercise more” has long been a go-to recommendation of physicians, many doctors are now beginning to write actual prescriptions for exercise, which include detailed “dosages” based on age and medical state. While these prescriptions may be largely based in conventional knowledge about exercise—it improves cardiovascular health and can aid in weight loss, reduce the risk for diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and high blood pressure, and so on—it’s not uncommon for exercise to be prescribed to those patients in need of improved mental health rather than physical. While this figure is rather outdated, a 1983 survey of 1,750 primary care physicians conducted by the Physician and Sportsmedicine Journal found that “85% of the physicians surveyed regularly prescribed exercise in the treatment of depression,” and according to William P. Morgan and Stephen E. Goldston’s aptly-titled book Exercise and Mental Health, the same treatment is often administered by psychiatrists, psychologists, and exercise scientists.

But why is the recommendation so prevalent? While many have heard that exercise does, indeed, “make you happy,” or have experienced first-hand the rush of finishing a hard jog or a tough practice, what’s actually occuring in the brain when the body exercises?

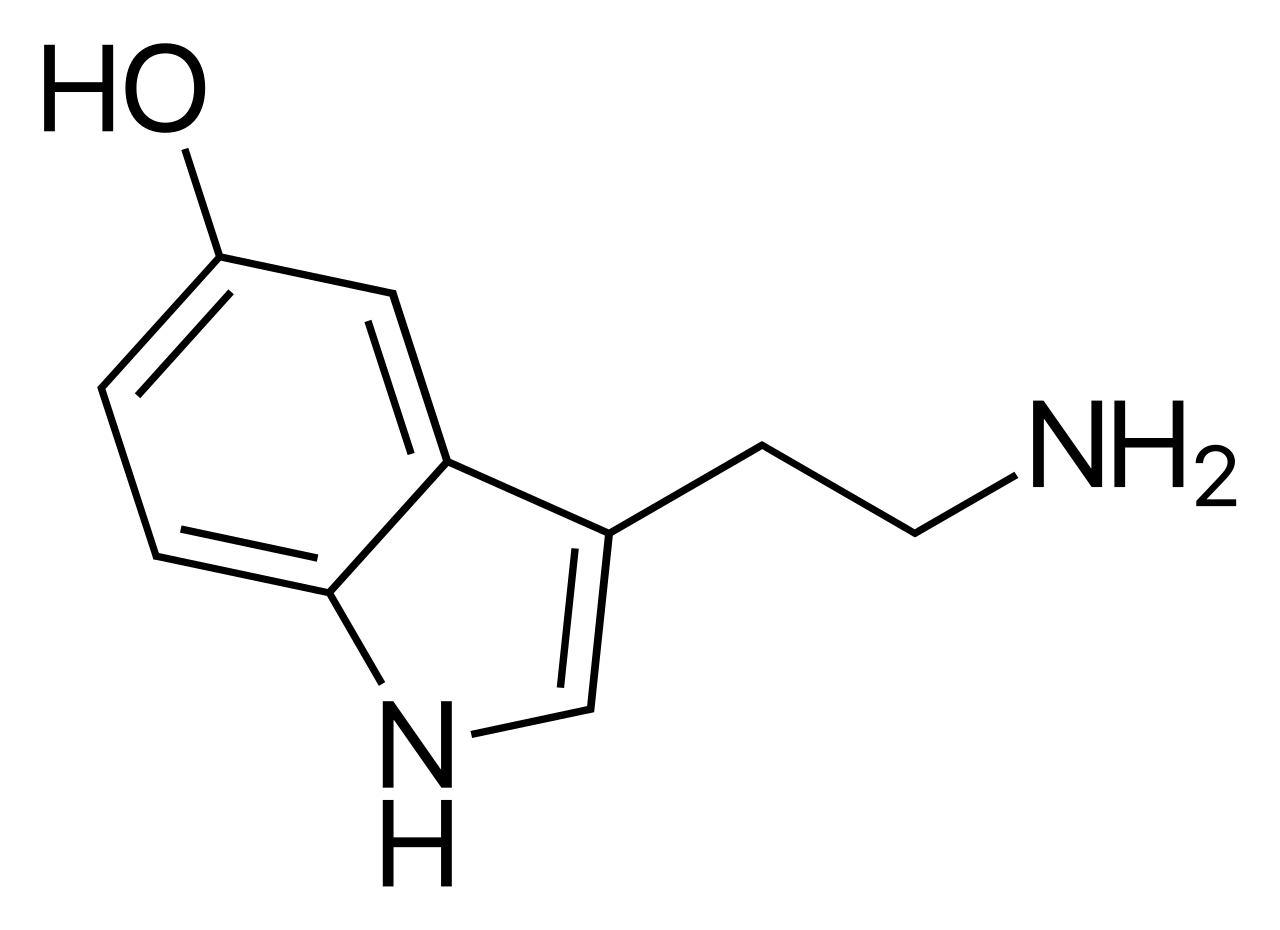

In basic terms, when one is exercising, the brain releases several chemicals; endorphins, dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. It’s the stress from the exercise that the brain perceives, and that triggers the release of the chemicals: according to a CNN Health article, blood plasma endorphin levels are elevated in response to stressors and pain. Those endorphins—which, interestingly, have a chemical structure similar to that of morphine—work to help relieve pain and stress, something that can manifest as a euphoric feeling after a workout.

But while there are conflicting reports about whether or not endorphins are actually connected to the joyful feeling linked to exercise, there’s general scientific consensus that any number of the neurotransmitters released during exercise, including the likes of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, are responsible. Serotonin, for instance, has been linked to depression: imbalances in serotonin levels which prevent the neurotransmitter from proper function can influence mood negatively, leading to depression, OCD, and anxiety disorders. Low levels of norepinephrine have also been linked to depression, and dopamine is also considered to be one of the “happy hormones” that functions in the brain’s reward system. It’s not hard to see why, then, an activity that spikes levels in all three could potentially influence overall brain function in a positive way—and counter some of the effects of mental health disorders caused by chemical imbalances.

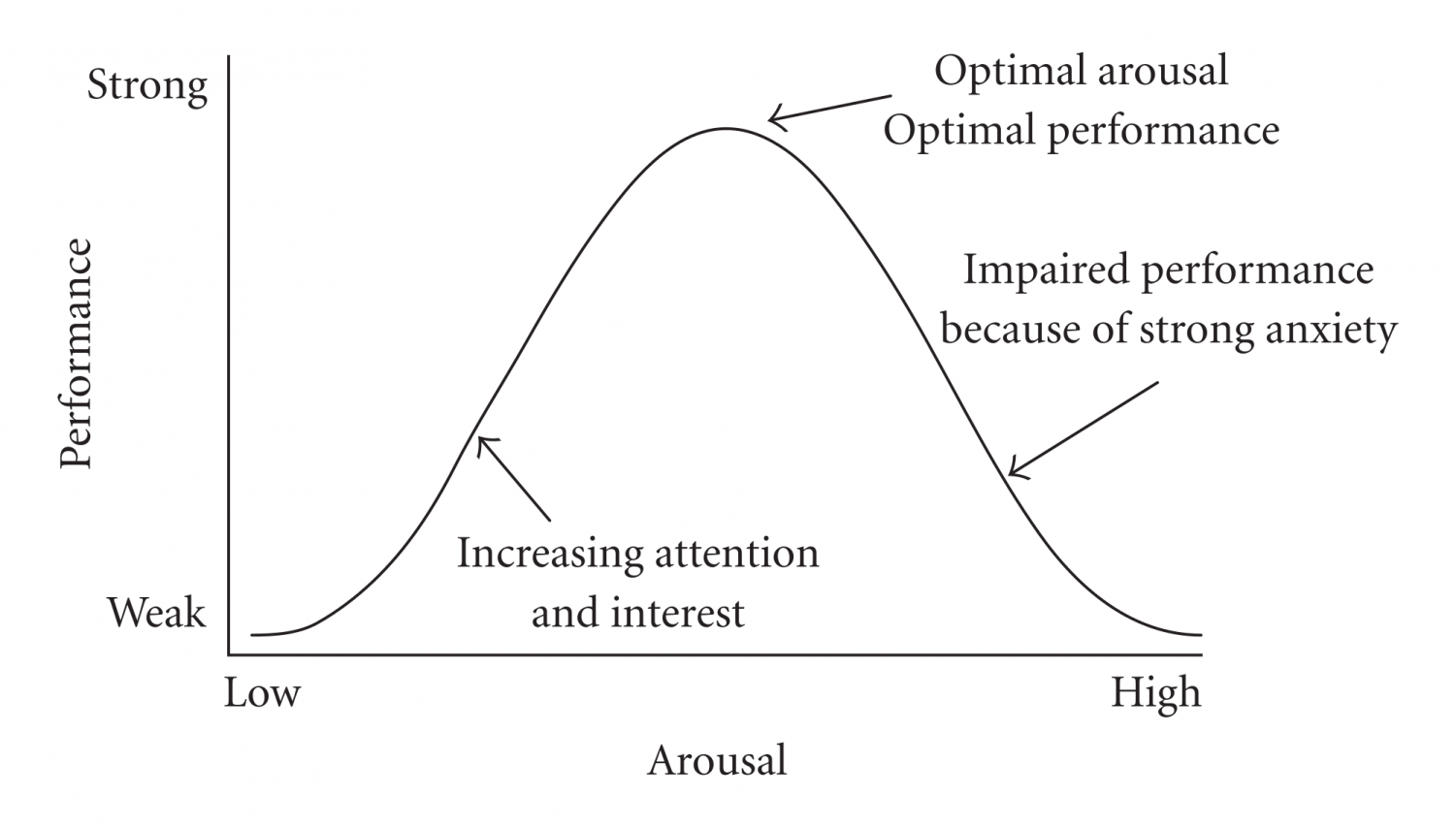

Of course, with team sports, other factors that could improve mental health will be at play: the close relationships and team bonds developed when playing a sport aren’t necessarily quantifiable, but individuals combatting depression must often cope with an overwhelming sense of loneliness and lack of purpose in life. While soccer practice might not give new meaning to life, it provides structure, something helpful in avoiding a desire to stay in bed all day or isolate oneself from friends and family. Moreover, bonding with teammates isn’t a guarantee, but a vast number of athletes who played team sports speak highly of the camaraderie that was as essential to the team as winning was, and oftentimes describe a kind of brotherhood or sisterhood—a unity—between teammates that rivals that of the closest friendships. Sports can also, in theory, be an outlet for healthy, incremental goals: go to practice, win a game, do team bonding activities. Competition itself can be a more tumultuous aspect of sports. While competition can certainly be a source of mental health distress, it can also be a source of eustress, which is considered the “good kind” of stress—the kind that benefits its experiencer, and pushes them to perform better, increases motivation and energy, and lasts only in the short-term.

But a conversation about exercise’s impact on mental health would be incomplete without discussing the other side of the coin: the distress, not eustress, that can be caused rather than absolved by exercise. Nothing is without risks. The positive effects of sports—particularly competitive sports—do not extend to all people, or all mental health conditions. For some, the pressure of an impending meet or important game can cause crippling performance anxiety. Often a team’s fate can be decided by a single play, a single throw, a single movement. That pressure can take a significant toll on those responsible.

There is another danger to athletics. In most sports, there exists an ideal body type or body structure. It’s generally easy to recognize: linemen are heavy, muscular, and agile; basketball players are tall with long legs and wide wingspans; gymnasts are tiny, flexible, and incredibly muscular; the list goes on. There is inherent risk to this. Idealizing a specific shape isolates those who deviate from the standard and can trigger body dysmorphia, often leading to dangerous eating disorders. While this is most publicized in sports that value thin female physiques, the dangers are not limited to a specific activity or gender.

Yet one key finding seems to tell a different—or at the very least, more complex—story: John S. Raglin’s 1990 review article “Exercise and Mental Health: Beneficial and Detrimental Effects” summarizes findings that showed that for neurotypical individuals—those not affected by mental health disorders—exercise either only improves mental health by a modest amount, or doesn’t improve it by any meaningful amount. For those with severe anxiety or depression, however, the improvements were of a much more significant magnitude. So while it’s common knowledge that exercise improves mental health, a central paradigm is being overlooked entirely: exercise appears to be preventative for neurotypical individuals. For neurodivergent individuals, exercise becomes a real, tangible form of treatment.

This means that the current COVID-19 pandemic presents an even greater challenge for neurodivergent individuals. Shuttered at home without the usual business of life to distract them from their potentially damaging thoughts, many people struggling with mental health can no longer take advantage of the positive physical and psychological effects that regular exercise can offer them. People dependent on the positive stress of exercise to improve their mental health are being forced to find other solutions or they risk falling back into negative cycles.

Victoria

For Victoria Soulodre, a heavy involvement in sports blossomed not from passion, but from need for distraction. While her primary interest lies in ice skating, a sport she participates in year-round, she’s been playing softball far longer—her mother signed her up to play when she was about six, the earliest she could start. She began her freshman year on Paly’s varsity softball team, a testament to the skill she’d been able to accrue, but her drive to play did not stem from the desire to become a talented first basewoman.

Even though Soulodre grew up the youngest in a family of four daughters, the considerable age gap between her and her three older sisters caused her to grow up feeling like an only child. Her parents tried hard to keep Soulodre’s childhood innocence intact, but it was impossible to ignore the constantly-looming threat of her older sister’s health.

“One [of my older sisters] is blind and has a lot of very bad health issues, so growing up, I would always deal with that,” Soulodre said. “When I was really little, my parents tried to keep me really happy. But in the background, there was always, like, the ambulance showing up at two in the morning for some reason, and that kind of became a norm.”

Soulodre says her parents sought out sports as a way to distract their daughter from a home situation that was equal parts unpredictable, frightening, and impossible to make sense of. Her day was always full to the point that she didn’t have much time to reflect on the anxiety surrounding her older sister: she was playing softball, soccer, and skating simultaneously, something that kept her busy and away from home as much as possible. Sports were a respite from the incomprehensible chaos that stemmed from her sister’s poor health.

While thankfully her sister’s medical challenges have improved—she’s moved to Fresno and is living on her own—the anxiety and turbulence that occured during Souloudre’s childhood left a significant mark on her.

“It was kind of a reality shock to me, like, ‘Is she gonna be okay?’” Soulodre said. “It kind of turned on me, being on my own. It was a big switch … I still have my sports to keep me busy, and seventh through ninth grade … I was fine, really happy, lots of friends. And then sophomore year was really rough.”

Describing her sophomore year is simple for Soulodre: in her words, she was simply intensely unhappy, all the time.

“Putting on that brave face while you’re in school, trying not to let others know how you’re feeling, [but] at home you’re like, ‘Wow, it was kind of fake,’” Soulodre said. “I would skip school, sometimes just to stay home because I couldn’t really get myself to go.”

Soulodre says that while the happy face she put on at school felt like a facade, her happiness in sport was genuine—playing sports was one of the only times she could take that mask off.

“Softball and skating … were the things that kept me really happy, and it wasn’t fake when I was doing that stuff,” Soulodre said. “It was real happiness, and [I was] surrounded by people who I knew I trusted.”

She remembers feeling like days and weeks would never end—she’d constantly be looking for the end of that day, willing time to move more quickly. In combination with feeling that time came to a standstill, Soulodre also vividly remembers just how alone she felt, no matter how many people were around her.

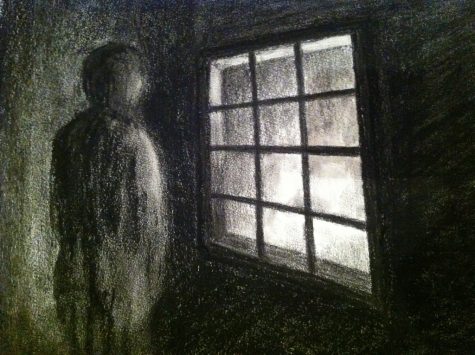

“I felt like I really didn’t have anybody even though I was surrounded by people who cared about me,” Soulodre said. “My mind kept telling me, ‘They’re not that close to you. They don’t really care that much.’”

I felt like I really didn’t have anybody even though I was surrounded by people who cared about me. My mind kept telling me, ‘They’re not that close to you. They don’t really care that much.

At first, she tried to convince herself that these feelings were normal—that everyone felt sad and alone sometimes. The difference in Soulodre’s case is that those feelings never went away, unless she was throwing herself into a coping mechanism. The question of whether someone is suffering from clinical depression, or whether they’re just experiencing normal teenage angst, arises often. The timing of mental health problems setting in is unfortunate; with the flood of hormones that hit during puberty, mental health disorders can develop in a time when adolescents are already expected to be moody and volatile. As such, many mental health patients don’t realize they’re even suffering from something more serious than typical mood swings, and are forced to question whether or not they’re just being dramatic or whether they have a legitimate condition.

“I never wanted to [take medication] because I didn’t want to accept the fact that that was what it was [that I was depressed],” Soulodre said. “I tried to keep telling myself, ‘You’re not sad. You’re fine. You don’t need to see somebody for this because you’re only sad when you’re home alone, and probably everybody else feels that,’ or ‘You’re struggling in school a little bit, everyone goes through that.’ It felt like you shouldn’t be dramatic, like this is what everyone goes through. Looking back, it really wasn’t.”

Despite her internal denial that she was going through anything serious, Soulodre knew that there were red flags she was ignoring. The depression began to negatively affect her sleep, and she found herself making constant excuses not to see her friends, despite her friendships previously having helped her escape depressive feelings.

“There was never really anything that I had to do the next day [when I said I was busy], it was just because I couldn’t get myself to go, no way,” Soulodre said. “If I did go out, I would have fun, but it was the feeling of ‘When you get back home, you’re gonna be alone again.’”

The one area of her life that depression didn’t taint was her passion for sport. Reflecting now, Soulodre says she realizes she was throwing herself into skating as a coping mechanism, but she doesn’t chide herself for doing so; she experienced her highest points when she was in the rink.

“When I would go to Winter Lodge and be on the ice, it would kind of all fade away,” Soulodre said. “And then the moment I got home, it would come right back.”

Her solution, at the time, was to simply delay going back home. While her depression often made her feel as though she couldn’t bear to go out with friends or go to school, she never felt that urge to skip a skating practice or go home early. Instead, she found herself filling as much of her day up as possible with ice skating.

“It was never something where I was like, ‘I’m too sad to go to practice,’” Soulodre said. “It was more like, ‘I’m really sad, I’m going to go to practice, I’m going to stay an hour late to do more stuff to stay on the ice to continue being there, I’m going to show up two hours early because I want to talk to the people there.’ It [depression] never kept me from skating. It always kind of pushed me to keep going.”

Being on the ice became a new addiction, as it was practically the only way for Soulodre to unshackle herself from the cloud of negative thoughts.

“I knew that when I was on the ice, or when I was playing soccer, everything else would go away,” Soulodre said. “But it was like, why do I need this to help fix my emotions? Why should I be relying on this? … I kind of used it as a coping mechanism when I probably shouldn’t have relied on it that heavily … but in the moment it felt like my logical solution.”

Her daily schedule quickly became hectic due to skating, but Soulodre didn’t mind the extra workload.

“Every Sunday, I would go in the morning, have my lesson work from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., and then if I felt like it I would skate from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m., because I didn’t want to go home,” Soulodre said. “I’d skate and then go home, eat dinner and go back.”

And naturally, putting in such an abundance of effort into her sport led to rapid improvements in her abilities, which only added fuel to the fire—on the ice, even if she felt confined most everywhere in life, she could make herself into anything she wanted to be.

“It really helped me get a lot better, like I improved really fast … just because when I was on the ice, I was pushing to be a better version of myself,” Soulodre said. “I would step on the ice and say, ‘Okay, you’re going to use this time wisely. This is your favorite time of the day … you’re gonna push yourself and you’re going to get better.’ And I’m kind of grateful for that in the sense that I wouldn’t push myself as hard [otherwise].”

While a common symptom of depression is a sharp drop in motivation or an apathetic attitude towards life—even towards previous passions—she found that skating helped her hone in on small goals that felt easier to tackle. She recalls one jump that she just couldn’t nail, no matter how much effort she put into it. While other tasks could seem daunting, one jump was something Soulodre could commit herself to, over and over again, for hours. She notes, too, that one of her primary sources of motivation were her coaches—she felt a need to make them happy, to make them proud of her.

Was that an unhealthy habit—the need to have others validate her efforts, working herself to the bone so her coaches would be proud of her?

Soulodre isn’t sure one way or the other. She knows that the innate competitiveness of skating brought out a certain competitiveness in her. She wanted to prove herself; at times, fulfilling that desire came at the cost of her own mental health. One source of distress was one of her best friends, who had always been ahead of Soulodre in skating. Soulodre would have to constantly watch her friend land perfect jumps, and berate herself for not being able to land the same ones; she saw her friends have solos in the seventh grade, whereas she was supposed to have her first just this year, and would doubt whether she was even good enough to be in the sport. She knew she was working just as hard as they were; she understands, now, that her body had its limits, but that didn’t stop the constant feeling of inadequacy.

She couldn’t control what her body could and could not do in the sport of ice-skating. But what she could control is how it looked, what shape and size it took on. Quickly, the initial insecurity over her abilities spiraled into a pattern of restriction and starvation spurred on by her peers.

“There’s these girls that practice with me that are like five feet tall, and they are tiny, but that makes sense because they’re in middle school,” Soulodre said. “But then I always look at them and they’re landing these advanced jumps because they’re small and they can rotate super drastically. Maybe I should look like that in order to land like that.”

And the sport she’d chosen to pursue only exacerbated that desire for thinness. Sports where a thinner body is seen as more valuable or capable, like gymnastics, ballet, diving, and figure skating, are notorious for the eating disorder risk factor they pose to athletes. Additionally, ice skating is a sport where individual performance trumps team effort—if an athlete sees themselves as the weak link due to their body weight, there is no ability to “hide behind” the team to mask that perceived flaw.

In Soulodre’s case, her ice skating team puts on their biggest show in April. Costumes for that show, however, are ordered in September to allow time for them to be custom-sewn and altered to each individual’s measurements. But eight months in between ordering the costume and wearing it is significant, especially for a sport dealing with adolescents: rapid growth spurts could cause a costume that fit perfectly in the fall to be impossible to wear in spring. The pressure to stay the same—not to grow, to remain small and competition-level fit, is immense.

“My measurements were different from September to [April] because I just grew a lot as a person, probably an inch, maybe two inches,” Soulodre said. “Most of them arrive in March, so a month before the show. You try them on—the costume doesn’t fit.”

She describes the panic she felt when she realized the costume was too small on her in March with just a month until the show date. Alterations weren’t a possibility, since the patterns were so specific and the backings must look the same on each skater—in Soulodre’s words, “it either fits you or it doesn’t.” Feeling trapped, Soulodre turned to extreme dieting in the hopes that she would be “small enough” by April.

“That month I restricted my eating a lot every single day, and I was also playing softball [along with skating],” Soulodre said. “Sometimes I would skip breakfast. And I would skip lunch sometimes … or I would eat a granola bar, that would be my lunch. And then I would go straight to softball after school … go home, eat something small … go to skate for like two or three hours and then go home and go to bed.”

She recalls how, despite the initial hunger she experienced from barely eating, she eventually got used to the extreme restriction. And with the end goal in mind of fitting into her costume—fitting into the idealized body type of a skater—slipping up in her starvation diet wasn’t an option.

“It’s kind of part of the bigger skating culture,” Soulodre said. “There’s this body that you think of when you think of a figure skater, kind of the way you would think of a ballerina or something like that. There’s that image, and that’s what you want out on the ice when [you’re] performing. So that kind of image stuck in my brain, like you have to make this fit. [If it doesn’t, it’s] embarrassing for you, even though it’s completely normal for your body to change in such a large amount of time.”

It’s kind of part of the bigger skating culture. There’s this body that you think of when you think of a figure skater, kind of the way you would think of a ballerina or something like that. There’s that image, and that’s what you want out on the ice when you’re performing. So that kind of image stuck in my brain, like you have to make this fit.

And while Soulodre could force herself to cope with barely eating, the malnutrition she was suffering quickly became evident in her sports performance.

“In softball, I [had] I think one of the worst seasons I’ve ever played, and my performance in games was awful,” Soulodre said. “There was one game … when I was playing, I tripped over myself, fell, and then I threw up in our shed and left early … And I think that was my body giving up a little bit.”

While sports often contributed to Soulodre’s struggles with mental health, she still credits them for serving such a therapeutic role in the hardest times in her life. She felt as though her mind was constantly overactive. But when she stepped onto the rink or the field, the goings-on of the world around her faded into nothingness.

“Your mind completely clears, like you forget about everything going on,” Soulodre said. “You just completely forget about it … that feeling kind of overruled everything else for the rest of the day … you played in the afternoon and then you just felt good for the rest of the day.”

Notably, when she recalls the moments she felt most free when playing her sports, they revolve around other people—her teammates, her friends. One of her favorite moments from her softball career is mercy-ruling Gunn, but when she relates the story, she focuses not on the dominant offensive performance her team put on; instead, she laughs when she mentions that some of the girls on Gunn’s softball team had been on her club team the previous year, so seeing those familiar faces and “crushing them completely” brought her joy. With ice skating, she brings up the incredible team dynamic during the dress rehearsal right before a big show—the feeling that you, as a group, are invincible.

“I was coming from a softball game, so I ran inside, got dressed super fast, put my makeup on, and it was this whole rush of adrenaline,” Soulodre said. “You’re just so happy in that moment. You’re like, ‘The show’s this weekend, it’s gonna be such a great day, it’s gonna feel awesome to get back on the ice with the curtain, the lights, the spotlight on you…’ Everything you’ve done for the past year goes out into your performance, and everything feels kind of worth it at that moment, the good and the bad …. All the work you’ve put in, the hours you spent on the ice… everything. You just spill out everything that day.”

Everything you’ve done for the past year goes out into your performance, and everything feels kind of worth it at that moment, the good and the bad. You just spill out everything that day.

Closing night was particularly sentimental for Soulodre—it was the culmination of the entire year’s work, the last chance to be on the ice with her teammates in front of hundreds of eyes. It was, in a word, emotional.

“For everyone on that team, because you’ve been working on that [show] for months and months and months, you’ve pushed through school, other extracurriculars …. It’s not like we’re winning an award or going to a competition and beating out other teams,” Soulodre said. “It’s for yourself. What you do is for personal satisfaction. So the fact that you got through these four months of grueling practices, [of] not being at home a lot, it’s just this big breath of fresh air when you finish. You just kind of exhale, and you’re like, ‘Wow, that was all worth it.’ You see the audience cheering you on, and you feel super special in that moment. And it makes everything feel worth it.”

And Soulodre knows that feeling wouldn’t have been the same had she not shared it with her teammates. According to Forbes, team sports can increase long-term happiness. While scientific studies back up the link between team athletics and a higher self-esteem and happiness overall, it doesn’t take a scientist to see why that link would exist. The team bonding alone that results from playing a group sport can lead to a sense of togetherness and unity, a sense that someone else is going through the exact same things as you are. And for Soulodre, the benefit of a communal experience was truer than it is for most.

“A lot of us had gone through similar stuff [regarding mental health] … and we just bonded on that and kind of laughed at our past because of it,” Soulodre said. “We’re like, ‘Wow, that was so miserable, but look where we are now.’ And we build each other up. One really fun moment for me was the day of our winter recital this past year … I spent the entire day there [at Winter Lodge]. I went in the morning with two of my closest friends from skating, [and] we spent the entire day there prepping, making little presents to put on the tree, we went to Target to do errands for our coaches … it just created a very special bond between the three of us because we spent so much time together that day and we just talked about everything that we’ve done.”

The bond that Soulodre formed not only with her friends, but with her coaches, was what kept her afloat in some of her most difficult times this year. Every athlete’s worst nightmare is an injury that takes them out of commission—for Soulodre, a concussion this winter prevented her from skating for a month. The loss of time spent on the ice would have been bad enough—she’d lost her happy place due to factors outside of her control, and went from skating for hours each day to nothing—had the injury not occured right before the big winter show. While Soulodre says the moment didn’t spiral her back to her lowest points, since she could still visit Winter Lodge daily and see her friends, the injury brought back some of the sadness she’d previously accustomed herself to.

While she thought performing in the winter show was out of the question, her coach took a leap of faith—and the risk paid off. Her coach struck her a deal: 10 days before the recital when Soulodre was medically cleared, her coach told her that if she was able to learn the entire routine from a set of videos, she could participate in the show. While the two routines she had to learn were brand-new, Soulodre had a secret she’d been keeping: while injured, she’d been following along with the routines on her own in her bedroom the entire time, mirroring the motions she would make with her skates barefoot.

“I stepped on the ice at that practice, and I did them [the routines] all the way through,” Soulodre said. “She looked at me and she was like, ‘It looks like you’ve been here the whole time.’”

She credits ice-skating for motivating her to work as hard as she did—for having the motivation to keep up with the routine even when there was a chance she wouldn’t perform at all. But she also credits it for allowing her to break out of her shell, and pursue activities that her depression previously would have prevented her from doing.

“There were a lot of moments [at the] beginning of the year like, ‘Maybe you should cancel your plans and not go to this tonight,’” Soulodre said. “[And I told myself to] just go, you’re gonna appreciate it, you’re gonna love it … if you wake up and you’re really hungry and you go to a brunch with a bunch of friends, you’re going to eat. Because in that moment, who cares? Eat some pancakes, order what you want, because it’s gonna make you happy in that moment … do what you want in life …. I knew how much fun I had skating. And I was like, if I could apply that to my outside life, it would just make me an overall much happier person. And that’s kind of what I did.”

While she credits skating for much of her personal growth—she notes she’s become much more outgoing, and generally less worrisome and anxious (or that at least, when she gets anxious, she’s better equipped to shut her irrational fears down and simply live life)—she hasn’t felt restricted by the pandemic. Winter Lodge has closed down in accordance with Santa Clara County’s shelter-in-place order, and all of Soulodre’s softball gear is still trapped in a shed at Paly, but she’s keeping an open mind. There’s a lot you can do off the ice, too, she says; and even if there wasn’t, she’s finding peace of mind elsewhere, something she never could have imagined doing last year.

“If this happened last year, I would be devastated.” Soulodre said. “I would probably get out of my bed at like one o’clock, walk around, eat some food, and go back to bed. I would have zero motivation. But this year, I was like, take this as an opportunity to get better, get more flexible, land your jumps off the ice so once you get back you’re stronger than ever.”

The one cancellation that has deeply disappointed Soulodre is that of the April show. But as she’s come to terms with the fact that the performance wouldn’t happen, she’s also understood that, as euphoric as the show itself is, the journey is just as rewarding as the destination.

“I look back, and in the past year, I’ve gone up a level …. [that] I was stuck in for three years … and I became a role model to a bunch of these younger girls throughout the team [who] look up to me, and I’ve made some of the closest friendships I ever had,” Soloudre said. “So when I look back at that, I really appreciate all that has happened in the past season. The show was kind of like the one small thing at the very end … to show everyone else what we’d been doing, but … [I experienced] personal accomplishment throughout the season.”

And she knows, too, that soon enough, she’ll be back on the ice. And she knows that when that happens, she’ll have her rock back.

“I always knew it was gonna be there,” Soulodre said. “[If] I was having a rough day, I could just show up and just sit there, and no one would question it … that place was my rock. It could be the lowest of lows or the highest point in my life, and I could be there and [it would] just make anything better.”

I always knew it was gonna be there. If I was having a rough day, I could just show up and just sit there, and no one would question it. That place was my rock. It could be the lowest of lows or the highest point in my life, and I could be there and it would just make anything better.

Even if by now, she’s grown past the point of her reliance on ice-skating to absolve her of worries or make the hardest days fade into nothingness, the sport has cemented itself as a defining facet of her personality. When she discusses the feeling of being on the ice, knowing it’s time to lay it all out for the audience, knowing there are no second chances, knowing her every move is being watched with rapt attention, it’s not fear or anxiety that shows on her face. It’s pure, simple: it’s happiness.

“It feels like everything you’ve done is worth it in that moment,” Soulodre said. “When you’re at your highest, you feel like you can kind of do anything. All my fear and worries would go away … you don’t really give a crap about what anyone else thinks in that moment. I could look ridiculous right now in this costume. And [I could be] doing a spin and falling out of it. I could look ridiculous. But in that moment, you don’t care what other people think…. Yeah, the praise of the audience is nice, but it’s all for you in the end. It gives you so much freedom: to just step on and be able to do the thing that you love the most.”

Naomi

To fully see Naomi Jecker-Eshel, you’d have to crane your neck and look up to a height of about 9 feet. She’s not a genetic anomaly who happens to have grown taller than most professional basketball players—she’s simply situated atop her horse, a resting place that she’s called home for years now.

Jecker-Eshel has been riding for nearly a decade, beginning when she was around eight years old and continuing on into high school. Now a competitive equestrian, she’s continued to ride all throughout high school for both an equestrian club and for a team. Riding had always been a reliable sidekick in her life—as she went through elementary school, a time when everything is new and foreign, and the fumbling, awkward middle school years, riding was there to turn to. As she grew up and matured, so too did her horse.

“I started riding when I was really young … which was really great!” Jecker-Eshel said. “It gave me a lot of structure and felt like something I could look forward to every week.”

But as she began high school, the immense transition in responsibilities and expectations began to feel more and more debilitating. While she’d expected that high school would feel more challenging or demanding, this was something different altogether—something that felt unmanageable.

“When I started high school, things in my life changed and school became a huge contributor to developing a pretty severe general anxiety disorder,” Jecker-Eshel said.

Anxiety wasn’t a foreign feeling for her, as she’d struggled with the disorder since she was a child. But she couldn’t ignore that the anxiety had developed into something that was threatening to swallow her whole, to the point that going through the duties of daily life felt impossible.

“Although I had struggled with anxiety since I was a kid, it had evolved into something incredibly debilitating,” Jecker-Eshel said. “I could barely go to school, take tests, and felt completely overwhelmed by daily tasks that are trivial to most people … like brushing your hair and stuff.”

I could barely go to school, take tests, and felt completely overwhelmed by daily tasks that are trivial to most people.

Consumed by chronic worries—many patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) describe feeling as though their entire life has been painted (and tainted) by a constant underlying dread—Jecker-Eshel most strongly remembers how hopeless the situation felt. Mental illness, as opposed to physical illness, is particularly dangerous for that reason: when your own brain turns into the enemy, and a cure isn’t as straightforward as taking antibiotics or having orthopedic surgery, hope can be hard to come by.

“I remember feeling like anxiety was something that would stick with me for my entire life; like I would be trapped with a brain that constantly hindered me from thriving in my environment,” Jecker-Eshel said. “I remember thinking to myself that living with anxiety for the rest of my life would legitimately make it a life not worth living … which was really scary.”

I remember feeling like anxiety was something that would stick with me for my entire life; like I would be trapped with a brain that constantly hindered me from thriving in my environment. I remember thinking to myself that living with anxiety for the rest of my life would legitimately make it a life not worth living.

And a diagnosis for mental illness can be far more complex than, say, diagnosing a broken bone. One is easily identifiable, and its symptoms concise: a bone fracture will be characterized by a complete or partial break in a bone, with accompanying pain, for instance. Anxiety and other mental illnesses, however, aren’t visible on the body, and can manifest in hundreds of different ways depending on the patient. Paired with the stigma that discussing mental health carries, it’s unsurprising that mental illnesses are severely underdiagnosed and undertreated. In Jecker-Eshel’s case, she may not have even registered that she was coping with something far beyond her own control without the intervention of a concerned friend.

“I realized that I probably had a mental illness when one of my best friends sat me down and talked to me about her struggle with mental illness, and how she thought I should see someone,” Jecker-Eshel said.

And she took that advice—Jecker-Eshel has been seeing a therapist for four years now, and says she’s “really learned how to live [and] deal with my mental illness.” But beyond clinical treatment, Jecker-Eshel sought relief from her rock: riding.

“I used riding as a coping mechanism and rode seven days a week, competed a lot and really threw myself into something I knew could give me the stress relief I so desperately needed from school,” Jecker-Eshel said. “When you’re riding a horse, it’s basically impossible to think about anything besides controlling a huge animal while trying to stay on its back over huge fences.”

The mental respite was welcome: one of the most common symptoms of GAD is a feeling that you just can’t turn your brain off, and that it’s constantly spinning and spiraling into worst case scenarios. The disorder is both mentally and physically exhausting, and the anxious thoughts are often both excessive in quantity and intrusive to the point of being impossible to ignore.

“This mindset that my brain was forced into every day I rode gave my brain the break it needed from the constant stream of thoughts and emotions that I had to experience throughout the day,” Jecker-Eshel said. “It felt like meditating, and I couldn’t achieve this level of relaxation any other way.”

Some might think that individuals suffering from anxiety would avoid competition at all costs, as it could spike anxiety levels or cause even more perpetual worries about not stacking up to your opponents or disappointing your team. For Jecker-Eshel, however, the experience was exactly the opposite: competitive riding gave her the extra boost she needed, and though GAD can manifest as an inability to relax or difficulty concentrating, when Jecker-Eshel competed, her mind finally cleared, and she was able to focus her thoughts only on the ride ahead. Moreover, her anxiety had shattered her self-esteem and made her question her every move and relationship, an exhausting mental process that left her constantly worrying about how she was perceived. Riding for a team filled with supportive teammates who quickly became friends, she saw her faith in herself slowly return, bit by bit.

“The transition I made as a freshman into the ultra-competitive riding scene gave me the confidence I so desperately needed when I won big competitions and received heaps of validation from my coaches and teammates,” Jecker-Eshel said. “Riding made me feel like anxiety didn’t define how successful I could be.”

Riding made me feel like anxiety didn’t define how successful I could be

Jecker-Eshel’s anxiety certainly didn’t define her success. Some of her favorite memories from the sport include triumphs on the national level, but what she remembers most from those competitions aren’t the shiny silken ribbons she was rewarded for her exceptional performance—it’s the feelings that flooded her when she competed that empowered her.

“When I was a freshman, probably at my lowest point with anxiety, my team qualified for nationals in Virginia,” Jecker-Eshel said. “I remember being with my teammates and best friends in this foreign place in the middle of the school year and feeling freer and more on top of my anxiety than I had felt in weeks. I ended up getting first in my division and our team placed 6th! I felt invincible.”

And riding wasn’t just a sport for Jecker-Eshel, something to occupy her mind. It became a practice, a tradition, and granted her a safe haven from the pressures of school.

“The entire ritual of riding made me incredibly happy,” Jecker-Eshel said. “I got to see my riding friends every day after school, could talk to my coaches about how my day was and what I was going through, and felt like I was part of a positive community not linked to high school.”

She acknowledges, though, that riding wasn’t always a healthy outlet for her to escape to. Just like any coping mechanism, it’s certainly possible to overdo it. In Jecker-Eshel’s case, she feels she quickly became too reliant on the sport to liberate her from the anxiety that was shackling her. In doing so, she realized she’d been “treating” her disorder with a detrimental obsession with riding, but that the treatment was more of a band-aid than a real remedy.

“Riding has not always been an extremely positive thing for my mental health, and as the years went by in high school, I started to develop a bit of an unhealthy relationship with the sport,” Jecker-Eshel said. “I started to define my worth by how many positive and negative comments I got from my trainers every day, and how I compared to my teammates. When riding started to transition into something not so healthy, I started riding less and less, but I think that’s also because I was easing out of debilitating anxiety by working through it with therapy, and was able to find purpose in other areas in my life.”

She’s not the same woman she once was in freshman year, and due to her own personal growth, Jecker-Eshel has found other ways to cope with her mental health when she hits low points.

“I’ve grown a lot since I was 14 and at my lowest point with anxiety … riding isn’t something that I turn to now.”

Weaning herself off of her reliance on riding to serve as a quick fix for anxiety was an essential step in Jecker-Eshel’s continued growth and management of her GAD. Now, it seems as though that step was more important than she could have ever realized back then; with the spread of the coronavirus and the subsequent shutdowns of large public facilities, Jecker-Eshel would have found herself stripped of her coping mechanism for months on end. Back then, that could have felt like a death sentence; now, though, she’s found other methods to keep her occupied, and has felt mostly content with her situation despite the cancellation of all of her riding competitions and the shutdown of her riding team’s training facility.

“This has been pretty okay for my mental health, [since] I’ve sort of outgrown my love for the sport and was mainly excited for the season to continue because I could be with my friends all day at competitions,” Jecker-Eshel said.

And there has been no shortage of team bonding despite the restrictions on face-to-face meetings.

“I work out with some of my teammates on Zoom using ‘home workouts’ which has been pretty fun,” Jecker-Eshel said. “I try to stay in touch with my friends as much as possible and go on socially-distanced walks with some that live close by to me.”

While there are certainly aspects of riding that she misses, Jecker-Eshel is trying to remain positive, and focus on what she can control rather than stressing endlessly about an uncertain future.

“I miss the aspect of being on a horse and with my friends and coaches … [but] I’m feeling okay! I’m optimistic about the future and praying that I can go to college next year. Remembering that there will be an end to the crisis keeps me going.”

For those struggling with similar feelings of despair and hopelessness that she once felt not so long ago, Jecker-Eshel offers some sage advice: mental illness won’t go away by magic, and treating it will take effort; sometimes it won’t feel like there’s a light at the end of the tunnel. There’s no doubt in her mind, however, that the effort is worth it. And that given enough time and effort, that light will shine through.

“You have to make active efforts to do things that will put you in a different headspace and alleviate some stress and sadness,” Jecker-Eshel said. “Dealing with mental health is work, like exercising a muscle that’s painful and difficult to target, but it’s something that you have to face in order to overcome [your struggle].”

Dealing with mental health is work, like exercising a muscle that’s painful and difficult to target, but it’s something that you have to face in order to overcome [your struggle].

Gabrielle

Gabrielle, who prefers to be cited with only her first name, is a staple in the Paly gym, known for her smile and her grueling ab workouts. Her story begins with an all too common circumstance: social discomfort and a body standard that she didn’t feel she conformed to.

“I started just being obsessed with how people would perceive me and the way I look,” Gabrielle said. “In my mind, I thought that people would be nice to me and like me if I lost weight, and if I was skinny, and if I was pretty, so I started dieting. I started doing tons of cardio, exercising way too many times a day. And it got out of control.”

In my mind, I thought that people would be nice to me and like me if I lost weight, and if I was skinny, and if I was pretty, so I started dieting. I started doing tons of cardio, exercising way too many times a day. And it got out of control.

Unlike Souloudre or Jecker-Eshel, whose struggles were hidden from friends and family, Gabrielle’s rapid spiral into an eating disorder raised flags among the people closest to her. Their concern ultimately became her lifeline, but at first she couldn’t bear their help.

Faced with overwhelming panic at a child whose health was deteriorating in front of their eyes, Gabrielle’s parents sought the only help they could think of: medical professionals.

Gabrielle knew how she was “supposed” to react. When the doctors told her to gain weight, she played along, nodding her head and promising to eat more. Deep down, she knew she wouldn’t listen. The thought playing on repeat in her head was I don’t want to gain weight.

“I was a sneaky person who would try to eat as little and exercise as much [as possible] and hide the fact that I was [still] losing weight from my doctors by like, sneaking weights into my doctor appointments and doing stuff to trick my heart rate so that they wouldn’t see that my heart rate was extremely dangerously low,” Gabrielle said.

Gabrielle’s struggle is one that many eating disorder patients can align with. As much as she wanted to be healthy, to be OK, there was a nagging panic in her head that wouldn’t allow her to gain weight.

At the time, exercise was a tool used to punish herself—to mold her body into submission—not something positive.

“I would still try to wake up early in the morning and exercise because that was terrifying gaining weight when I didn’t want to and my parents took the door off my hinges, they installed cameras all over the house to make sure that I wasn’t doing something I wasn’t supposed to be doing,” Gabrielle said.

For a long time, this attitude stuck. Eating disorders are most commonly a combination of two things: an extreme calorie deficit and an excessive amount of exercise. This means that instead of prompting “happy hormones” like dopamine, serotonin, and endorphins, exercise can be a negative stressor, associated with feelings of worthlessness, inadequacy, and shame.

“When I was trying to lose weight, exercise was a punishment,” Gabrielle said. “I would dread it every single day but like it was something that I kind of just had to do. It felt very cold, actually exercising felt cold, and it felt isolating, and I felt as if I was keeping this little secret to myself, but nobody else knew.”

When I was trying to lose weight, exercise was a punishment. It felt very cold, and it felt isolating, and I felt as if I was keeping this little secret to myself, but nobody else knew.

To her surprise, though, exercise morphed into a tool for her recovery. Faced with the prospect of returning to a healthy weight, Gabrielle discovered a way in which to manage that. Lifting became her solace.

“It was something that made me happy and that I could actually look forward to during the day rather than dread it,” Gabrielle said.

Lifting allowed her to gain the weight she needed. Instead of feeling hopeless and helpless during her recovery, it made her feel like she was in control of her body. From this, she says, she was able to appreciate and even enjoy the changes to her body.

“Gaining it through hard work actually made me very proud to gain weight, which was a really weird concept for me,” Gabrielle said. “Lifting had an emphasis on being strong, and being able to pick up and lift these heavy things. And that kind of changed my mentality around fitness, that fitness wasn’t something that changed the way that your body looked. Fitness wasn’t about wearing yourself down. It’s about building yourself up.”

That kind of changed my mentality around fitness, that fitness wasn’t something that changed the way that your body looked. Fitness wasn’t about wearing yourself down. It’s about building yourself up.

Now, amidst a global pandemic, many of the things that Gabrielle relied on to prop up her recovery are inaccessible. She cannot go see friends, who she credits as being the force that got her out of her eating disorder and back into a healthy state. She cannot go to the gym, which was the reason she learned to love her changing body. Yet even so, she’s doing alright.

“Exercise has kind of been my coping,” Gabrielle said. It’s a way that I can just like have something to do”

“You can do exercises anywhere,” Gabrielle said. “What I really miss most about the gym is the people and the diversity of equipment that I can use. We have a treadmill at home, we have some weights, we have a punching bag. I’m kind of just thinking outside of the box. I guess. It really sucks.”

The most important thing, though, is that Gabrielle reports a lack of regression in her mental health journey. While she’s had to return to cardio-intensive exercises—staples of her panic-fueled eating disorder workouts—her change in mentality means that she can accept them as part of her regular routine.

“I’m actually pretty proud to say that I haven’t gone back to those eating disorder thoughts and mentality that I’ve had with cardio,” Gabrielle said. “My new mentality is that the heart is a muscle that I want to get stronger. I’m trying to think more about how can I do better rather than how can I burn more calories.”

Gabrielles progression represents both the distress and the eustress that exercise can bring. What once was the most isolating and painful part of her routine is now the light that gets her through it.

Sebastian

Sebastian Long, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, never catalogued his turbulent relationship with eating as a mental health story. If you asked him to pinpoint the start of his rocky relationship with food, he couldn’t tell you—it’s been a part of ordinary life for him for as long as he can remember. There is no beginning, middle, and end, no slow exposition or resolution that ties up loose ends. When disordered eating patterns become just that—patterns, ingrained and solidified to the point that they become the new normal—you don’t see yourself as someone who’s fallen victim in a mental health plot, says Long.

But despite what’s been practically a lifelong struggle for Long, something as normalized to him as regular eating patterns are to others, he knew that the constant ups-and-downs in his self perception, in the dietary manipulations he relied on to control that self-perception, weren’t typical.

“I’ve never really conceptualized my mental health as a story, but I suppose thinking about it there are two main facets to it,” Long said. “I have what I’m pretty sure is a higher than average level of anxiety, which has fluctuated in how much it impacts me day-to-day, but the larger side to the mental health problems I’ve encountered has to do with eating and body-image issues. I think it would be near impossible to pinpoint a start because I’ve felt these things for about as long as I can remember.”

Although his difficulties pertaining to body-image lack a definitive beginning, his athletic career began far after he’d grown accustomed to malnourishment. As a teenager growing up in St. Louis, Missouri, athletics were never part of Long’s high school career. Only after the transition from his Catholic all-boys school to attending university did Long begin to play organized sport. A walk-on to the crew team, Long says that rowing was the spark that led athletics to become a central focus of his days.

But the potent self-awareness of his body had been a part of his life long before that first freshman year of college.

“Since being afraid to play shirts and skins soccer in fourth grade, I’ve always been self-conscious about my weight and my eating,” Long said.

The emotional turmoil surrounding his body hasn’t gone away over the ten or so years since that memory. What has changed is the extent to which food controlled him, and to which he tried to control food—it’s dwindled at times, and grown to an oppressive influence at others.

“In high school, I was on the border of obesity and had issues with binge-eating, and when I lost a ridiculous amount of weight my senior year of high school it was partly due to restrictive eating,” Long said. “Even now, the time in my life where I am most secure with these issues and have mostly healthy habits, they still manifest as body dysmorphia, over training, and restrictive eating.”

Even now, the time in my life where I am most secure with these issues and have mostly healthy habits, they still manifest as body dysmorphia, over training, and restrictive eating.

His experience reflects a notion many individuals who’ve fought eating disorders will recognize: even when in recovery, true “healing” can often seem far off. Even if the person begins eating a proper amount, the idea that all disordered thoughts disappear and food is truly viewed as fuel without inducing feelings of guilt, fear, or panic may be, in the short term, impossible. Medically, the general consensus is that individuals can be “in recovery.” But the question of whether a person is entirely free of the eating disorder is murkier.

In an interview with the New York Times, Dr. Kathryn Zerbe, an expert on eating disorders and a psychiatrist based in Portland, says she believes anorexia can indeed be healed.

“I do believe that people can be healed, even after a lifetime of struggling with an eating disorder, so it is worth ‘pushing yourself,’” Zerbe said. “Getting better should be about a lot more than just dealing with the eating symptoms and weight fluctuations. It means dealing with feelings, wishes, fears and any hidden meanings that underlie the problems. I tell my patients that we all have a psychological relationship to food.”

Long is living proof that it’s possible to bounce back even from the lowest points, when recovery seems impossible. But he’s also living proof that eating disorders aren’t as simple as an A to B recovery plan, where one goes from disordered to cured through a few weeks of treatment. It’s been important to him to acknowledge that even though he’s certainly in a better place than he was at his worst, he’s still addressing those deeply-entrenched insecurities and preoccupations with food and self-image.

“Not to say I’m numb to the pain of it, but at this point accepting that I have these issues has been one of the most helpful steps I’ve taken,” Long said. “In fact, earlier this year I picked up a minor injury and wasn’t able to exercise for a month or so, causing me to eventually realize I hadn’t just put these issues behind me and trying to shove them away was probably only making them worse.”

At this point accepting that I have these issues has been one of the most helpful steps I’ve taken. Earlier this year I picked up a minor injury and wasn’t able to exercise for a month or so, causing me to eventually realize I hadn’t just put these issues behind me and trying to shove them away was probably only making them worse.

An injury that forcibly put Long out of commission was the catalyst for dredging up some of those old feelings that he’d been making an effort to bury. Just as exercise in moderation can be healthy, even beneficial to individuals coping with poor mental health, the principle that too much of a good thing becomes a bad thing applies. Over-exercise is often a symptom that accompanies eating disorders as a complement to extreme calorie restriction; while someone obsessed with working out can appear to be healthy externally, the line between a commitment to fitness and an addiction can be blurred. Those with eating disorders often rely on exercise and sport either as a punishment—those who “slip up” and indulge in a 100-calorie treat, for instance, will often respond by exercising until they’ve burned off an equivalent amount of calories—or as a tactic to spur further weight loss. And sports serve as an effective mask for eating disordered patients; it’s hard to see an extremely-low calorie diet as anything but harmful, but playing soccer or running track for a few hours a day can be seen as healthy. Even those with eating disorders can lead themselves to believe that their over-exercising is actually a healthy habit, not a symptom of a preoccupation with food and weight.

It’s why Long has trouble describing his relationship with athletics—to say it’s been purely positive or purely negative would be disingenuous. So while he’s enjoyed his experience as an athlete, sports have been a double-edged sword for him.

“To say my relationship with athletics is complicated would be an understatement,” Long said. “I love the sport I compete in, I love my team, and I genuinely love working out; I have gained invaluable skills and such an appreciation for what my body can do. But at the same time, I sometimes put extra pressure on myself because of it and things get worse.”

Indeed, while the competitive nature of sports can serve as a motivator for those with depression or related mental health struggles, they can also serve as a serious trigger point for those whose disorder centers around competition and control. Eating disorders, particularly, can manifest as an intense form of self-competition. With restrictive eating, even if the vast majority of the general population begins to view you as thin (the preliminarily “goal” for many eating-disordered individuals), thinness in their eyes becomes unsatisfying. Seeing oneself as thin, through one’s own eyes, becomes the new goal—and that goal is often impossible to attain.

In combination with body dysmorphia, something Long struggled with, eating disorders become particularly dangerous. Body dysmorphia affects self-perception—even if the individual is severely underweight, they can perceive themselves as looking overweight, for instance. Restrictive eating is target-focused—if what’s in the mirror never looks good enough, the objective becomes seeing an ever-smaller number on the scale. Victory can take many shapes—a loss of a few pounds, bones becoming more visibly defined—and defeat is rooted in gaining weight. A disorder so competitive in nature, one that distorts the very meaning of winning, can be compounded by playing sports in which triumphing over the opponent at any cost means everything.

“It would be tempting to say that my low point was the middle of high school, when I was overweight and felt isolated and hopeless,” Long said. “Instead, my low point was this year, when stress and overtraining really did a number on me.”

But being part of a team did offer one clear benefit to Long: he and his teammates became part of a brotherhood he could lean on when he felt too afraid to discuss his mental health with his family.

“The one upside of this [having my lowest point this year] is that I did seek out my school’s mental health offerings and began to open up to a few of my close friends, some on the team,” Long said. “I think the biggest thing both of those helped is the feeling I had always had that I was alone. To me, that was always the hardest part—the feeling that no one understands or that something is wrong with you. Having others support me and let me know that there was nothing wrong with me has gone a long way to making things better.”

To me, that was always the hardest part—the feeling that no one understands or that something is wrong with you. Having others support me and let me know that there was nothing wrong with me has gone a long way to making things better.

And while the pandemic has caused a significant alteration to Long’s normal routine —he’s back at home in St. Louis, where “rowing is pretty much out of the question for now”—he’s still found ways to stay active. But despite his flexibility, COVID-19 has had a distinct negative impact on him. Primarily, he’s struggled being back at home, as he’s still not told his family about his last few volatile years.

“I still haven’t told my family,” Long said. “[I’m] not really sure how to, partly because I don’t want any of them to look at me differently or feel bad.”

“I’m not able to exercise as much at home, I don’t have access to the same mental health help or nutrition, and I don’t have people with me who know,” Long said, noting that he’s been spending his days running and working out in his backyard as an alternative to organized sport.

Nevertheless, he’s tried—and succeeded—in finding some silver linings in what could have quickly turned into a period of decline for his mental health.

“At the same time, having a reprieve from the constant stress of school has been nice, especially as I had been having a tough few weeks before everything changed,” Long said. “My support system at this point is essentially the close friends I have that know, and the biggest thing I’m focusing on in quarantine is creating a sustainable schedule that involves work, eating, exercise, and sleep.”

Long realizes that he’s in an unprecedented time—a “mixed bag,” to be sure—but that he’s also, in some ways, been granted a unique opportunity to take the time to rehabilitate the long-fraught relationship between him and his body. It’s complicated—like any other relationship—but Long feels ready to undertake the process of mending his self-image.

“I’m trying in quarantine to redefine my relationship with exercise and being outside in general,” Long said. “I’m playing more with my younger siblings, sometimes going on a nice walk instead of a run, and trying to focus on long-term stability rather than just working out to feel comfortable with my body in the mirror afterwards.”

And while he acknowledges that “repairing” one’s body image isn’t quite as simple as it sounds, the first step towards recovery is often the scariest: embracing vulnerability.

“I don’t really know if I’m qualified to give advice, but I think the one thing I can say with certainty is that talking helps,” Long said. “Getting something out of your mind and into tangible words, telling another human being who cares about you—these help more than I could have imagined.”