Title IX: 50 Years of Progress

A little girl in Illinois sprints down the ice. Her parents cheer from the sidelines as she winds up and sends the puck flying into the goal. She throws her arms up in victory and her teammates surround her. A young woman in Texas winds up for a pitch. Her arm swings around and the ball is sent into the catcher’s mitt with a thud. Strike! She pumps her fist and wipes sweat off her brow. A girl in Hawaii holds the water polo ball, waiting for the ref. Tweet! She rises up out of the water and hurls the ball under the goalie’s arm. She grins and high-fives her teammates as they swim back to half-court.

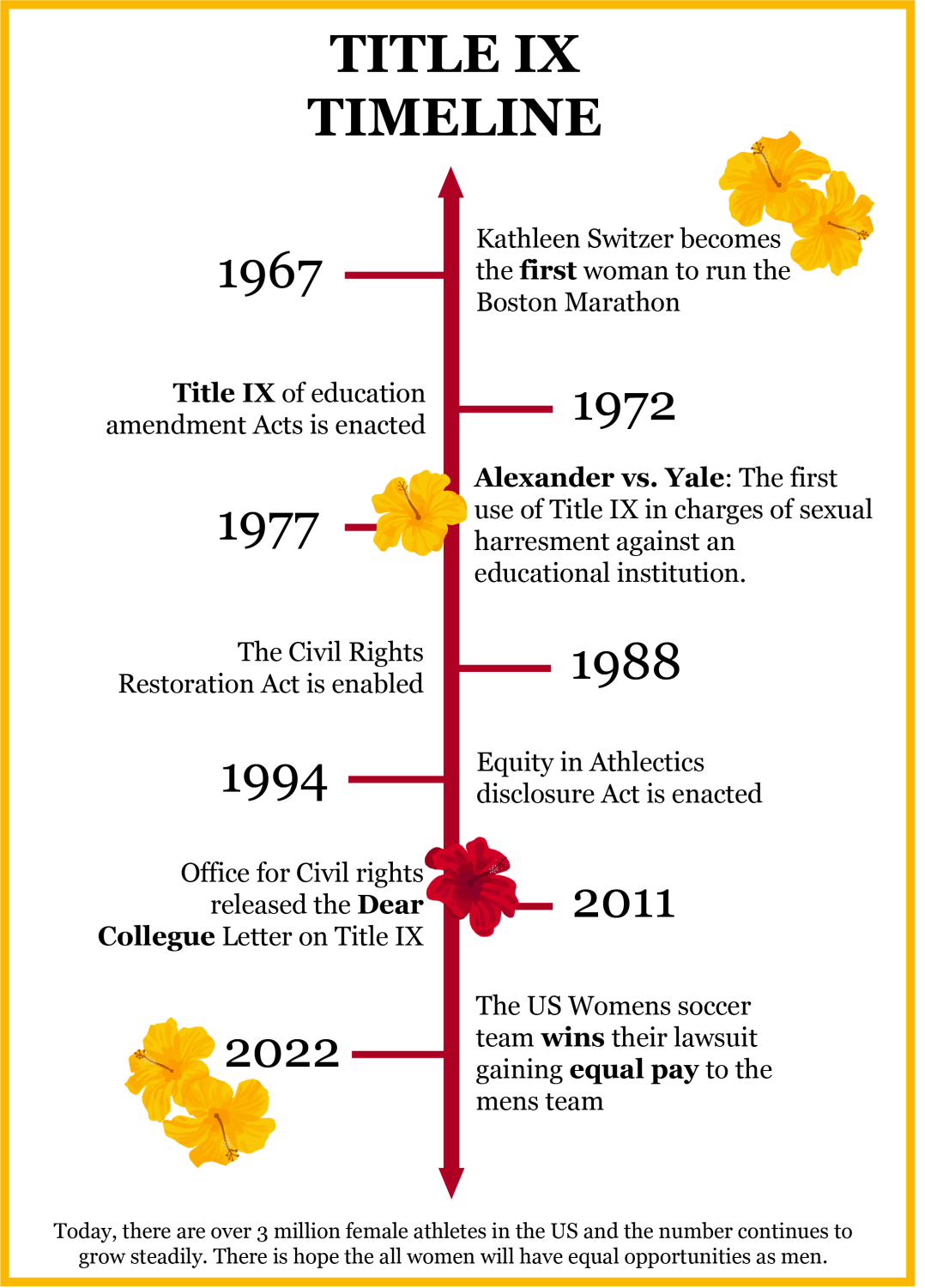

Girls all over the US are playing sports, with their schools, clubs, and friends after school. Sports are a huge part of American culture for women. A plethora of things have helped this reality come to be, but one of the most keystone accomplishments for women’s sports was on June 23rd, 1972, when the US Congress passed Title IX of the educational amendments to the civil rights act.

This law prohibits discrimination in educational programs and activities that receive federal financing. It required private universities and sports organizations to address any report of sexual harassment or misconduct and actively work to prevent it. The passing of Title IX was an astronomical step for women in all walks of life especially in athletics.

Representative Patsy Mink, Representative Edith Green, and Senator Birch Bayh were the major writers of this legislation. Rep. Mink of Hawaii, being the biggest contributor, wrote this legislation in reflection of the struggles she faced as a woman in her education.

However, the legislation received quite a bit of backlash. Senator John Tower, a Republican from Texas, wanted to restrict Title IX by proposing the Tower Amendment, which exempted any athletics from the conditions of the legislation. Had Tower’s amendment passed, female athletics all over the nation would likely never have grown to the importance and prominence that they hold in the lives of many women today.

Once Title IX was passed, many school districts started hiring Title IX coordinators. While these individuals are in charge of the legal side of these issues, members of the community still need to step up in order to see change.

Kelly Gallagher, who has over a decade of experience in administration at schools, was recently appointed as the new interim Title IX coordinator for Palo Alto Unified School District in the summer of 2021. Gallagher played a significant role in enforcing and processing Title IX at Columbia University and wants to continue doing so for PAUSD.

“My responsibility primarily is to receive and review reports that may meet the definition of sexual harassment and sexual harassment as inclusive of interpersonal and sexual violence—respond to those reports by providing resources and support and then people’s rights,” Gallagher said.

Gallagher puts heavy emphasis on providing important historical information for the school administration.

“In the 1970s when Title IX came to be a law, the law was to address inequities in how women had less access to educational opportunities than men. So at the time, women were restricted from participating in the joining of certain colleges and universities,” Gallagher said.

Now, women have more job and educational opportunities, and girls all over the nation play sports from a young age. Athletics are so ingrained in many girls’ and women’s lives that for many women today, it seems impossible to imagine a life without sports.

But when did women begin playing sports? According to Richard Bell of the Sport Journal, one of the first recorded examples of women playing sports was written by Homer around 800 B.C., when he wrote about Princess Nausicaa playing ball with her handmaidens on the island of Scheria. According to the Penn Museum, unmarried women in ancient Greece also had the opportunity to participate in athletic competitions during the festival of Hera.

However, over time in America the role of the ‘traditional’ woman changed significantly. Women, prior to around 1862, did not have the right to control their own money or own property, and before World War I women’s sports were extremely rare and considered to be more recreational activities rather than competitive or formal athletic events, according to Bell.

The biggest shift for America was seen during World War II. When the men went off to fight, American women ruled the baseball scene. Melvin Porter for How They Play writes that over half of the Major League Baseball players had left to join the effort, and the sudden absence of male baseball players left women to step up and take their places.

Many Americans, including President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, felt that women playing baseball in the major league fields would bring cheer and hope to the American people during the war, as well as keep baseball alive while the men were gone.

As a result, the All-American Girls Softball League was formed. Many women who formerly played recreational softball were recruited to play in the league.

People were happy to see women playing baseball. However, this was only because they liked to watch baseball and there were no men to play it. These female athletes were meant to keep the sport alive, not to actually hone their skills as professional athletes. Their identities as women were meant to come first. They were told to ‘play like gentlemen and act like ladies.’

After the war was over, men came back and reclaimed their former position in American baseball, and the number of female professional athletes decreased sharply. However, more young girls became interested in sports, marking the quiet beginning of the female athletic movement.

And it was a quiet beginning indeed. Before Title IX was passed, women’s sports were always considered to be the last priority. Equity Online, a site for information on the Women’s Educational Equity Act, found that prior to the passage of Title IX, women’s sports received less than 2% of collegiate athletic budgets. Scholarships for skilled male athletes were common, but it was virtually unheard of for talented women to receive athletic scholarships.

The Women’s Educational Equity Act also found that in 1971, the year before Title IX was passed, there were less than 300,000 girls playing varsity sports at their schools. This means that women made up a measly one percent of all high school varsity athletes prior to Title IX.

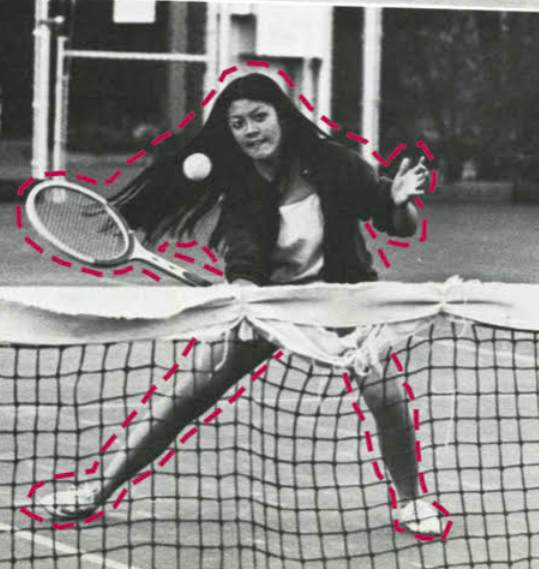

Susan Spencer is 79 years old, and she played every sport offered at her all-girls school during the mid-1950s: field hockey, tennis, softball, and basketball.

“Girls’ sports were not at all important,” Spencer said. “It was not anything you’d want to pursue because, at that time, you only went to college to pursue a husband.”

There were all sorts of misguided ‘scientific’ techniques frequently used to keep women out of the athletic scene.

When Kathleen Switzer became the first woman to run the Boston Marathon in 1967, race organizers tried to rip off her bib numbers and drag her off the course, according to the BBC.

Switzer recalls the reasoning behind forbidding her to run, which were the same reasons that men used to keep women out of sports for decades.

“[It was thought] that their uterus might fall out, … and maybe they would grow hair on their chests,” she said.

Occurrences like this were common in high school sports as well.

“We could only take three dribbles, you couldn’t go up and down the court all the way,” Spencer said about her high school basketball team. “Girls couldn’t do that. Boys could, of course. They thought it was too strenuous [for the girls]. We had to stop after three dribbles and pass the ball.”

In 1972, when Title IX was passed, discrimination on the basis of gender in education was banned. This caused a tidal wave of changes for women all over the nation, in many different fields. More women began earning college degrees, and both women and men now had access to jobs previously restricted by gender.

Of course, Title IX also had a large impact on female athletes. Forty years after the enactment of Title IX, women’s participation in sports had risen by ten times — to over 3 million female athletes across the nation — according to the Women’s Sports Foundation.

Now, women’s sports are encouraged, participated in, and funded at similar rates to men’s sports in America. Female athletes are also prioritized in the US more than in any other nation, largely due to Title IX.

The effects of this prioritization can be seen with the US women’s medal count at the Olympic games. The summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, 2016, were a prime example of the dominance of female American athletes on the world stage.

Jeré Longman for the New York Times notes that had the US women been their own country, they would have been 3rd in the overall medal count, behind the entire nations of China and Britain, respectively, as the women won 61 medals overall in 2016.

Bill Plachke of the Los Angeles Times notes that this is due to the effects of Title IX. More girls participate in sports in the US, and women’s sports are prioritized equally under the law.

Mariya Koroleva, a synchronized swimmer who moved to Northern California from Russia when she was 9, compared the effects of Title IX in an interview with the Los Angeles Times.

“In Russia growing up, the boys did sports and the girls did the knitting and housework,” Koroleva said. “[There is] so much more opportunity here, all girls can play sports, that’s the great thing about our country.”

However, discrimination is still present, and many female athletes feel sexism affects them and their sports.

Rachel Ho (‘24) has been on the Paly dance team since her freshman year and has observed that female athletes are inherently viewed differently compared to male athletes.

“Whenever female bodies often do things, it’s more scrutinized than when men do it,” Ho said.

Ho is not alone in facing sexism and misogyny in sport. Paly graduate Yael Sarig ‘20 is now at Brown University. She has struggled with finding female empowerment in her athletic spaces. Sarig describes how she felt sexualized and unwelcome in the Paly weight room.

“There are a lot of systemic things I take issue with, especially when my friends say they want to start weightlifting but feel crowded out or intimidated by the number of men in the gym,” Sarig said.

Sarig notes the number of microaggressions she experienced while being an athlete at Paly. If squat racks were all taken, boys would come up to her first and ask how many reps she had left. When Sarig lifted heavy weights, boys would come up to her asking who had taught her how to do that. The worst comments she received in the weight room were because of the way she dressed.

“One time I wore a sports bra and leggings and when I left then came back from getting water, my friend told me about the slut shaming comments about me. But the boys are wearing stringers and tank tops that are just as exposing as my sports bra,” Sarig said.

Another Paly graduate, Kylie Mies ‘21, now playing volleyball at Pomona College, finds similar issues regarding high school boys making inappropriate comments about her team.

“Because of the clothes we wear, the focus shifts from us being athletes to our looks. They don’t understand that it is for us, it is for women. We have a passion for this sport, we want to get better, we want to win,” Mies said.

Female athletes have been harassed and objectified for years, and Title IX requires schools to address any reports of harassment. However, many women may not feel supported in coming forward with their experiences due to a lack of action.

“I feel like it is difficult because you don’t want the whole world to know, but you also want to feel comfortable on campus,” Mies said.

Some students suggest having a student representative on the board so that adults have a student perspective. It is ingrained into the minds of young female athletes that they cannot speak up about something that made them uncomfortable. This is worsened by the fact that administrators often fail to take suitable action regarding the reports they receive.

Beyond just facing sexism and harassment, female athletes have had to fight for their rights to play and to be treated with the same respect as male athletes are.

Just this February, the US Women’s Soccer team won their class-action lawsuit against the US Soccer Federation demanding equal pay. According to NPR, this began in 2016, with five high-profile players filing a complaint due to their lower pay. The movement then grew into a lawsuit in 2019. In May 2020, a judge dismissed their claims, and the team had to challenge again. Now, two years after the dismissal, the reigning world champions won their appeal and the federation promised equal pay to the men’s national team.

Along with unequal pay, women’s sports also don’t get the same type of support that men’s sports do. This has been a problem all throughout history.

“Nobody wanted to cheer for us, but we played because we liked playing sports,” Spencer said. “But it wasn’t anything that people came to watch.”

The same underappreciation for women’s sports persists to this day, seen in the low audience turnout for women’s athletic events. These inequities exist here at Paly as well. Many female athletes notice their games are attended much less frequently than the boys games of the same sport. Fans are empowering, which can make all the difference in performance.

During a recent Paly versus Gunn girls basketball game, there was a stark increase in the number of fans which led to a very powerful environment for the athletes, helping lead Paly to victory in the crosstown rivalry match against Gunn.

“We usually don’t get any [fans,] so it was such a different environment to play in,” McKenna Rausch (‘23) said.

More than just game attendance, women’s athletic programs all over the nation remain in the shadow of men’s athletics.

Since 1972, for every dollar spent on women’s college sports, two have been spent on men’s college sports. This is evident in equipment, advertisements, and coaching staff for female collegiate athletes.

Learning and understanding what needs to be done next is crucial for the future of women’s athletics. Paly needs to continue working on equality for women, whether it is including more equality lessons for coaches, making sure female athletes feel respected and safe, or encouraging students to attend women’s sports.

As our nation changes over time, Title IX continues to get more and more politicized. This politicization has been very apparent over the past fifteen years.

“Title IX is driven by what our state laws are, and what our federal laws are,” Gallagher said.

Gallagher and the rest of the Title IX team at PAUSD have been talking about changes that they hope to make in order to make Title IX more effective in the district.

“We anticipate proposed changes later in the spring, then those changes would become effective under the law next year. And so we’re constantly making sure that we are up to speed. Not just the best practice of ‘how do we respond to these things in a way that is thoughtful and informed to the trauma that people have experienced’, but in a way that we’re also being compliant with the law under both the federal government and the state government,” Gallagher said.

“We anticipate proposed changes later in the spring, then those changes would become effective under the law next year. And so we’re constantly making sure that we are up to speed. Not just the best practice of ‘how do we respond to these things in a way that is thoughtful and informed to the trauma that people have experienced’, but in a way that we’re also being compliant with the law under both the federal government and the state government,” Gallagher said.

Former Paly softball player Ella Jones (‘20) is now at Bowdoin College. She describes what she thinks educating athletes should be about.

“I think it should be about empowering young girls not to be scared about what they want to do,” Jones said. “Teaching them [that] there is a place for them in athletics. It teaches girls to be physically and mentally stronger, empowering themselves.”

Female athletes through the years have stuck together, knowing that they are always there to support each other.

“It’s all about finding that group of people that best supports you, making sure that you feel good and they always are trying to lift you up, not put you down,” Ho said.

With a supportive group –—whether the team is official or not — female athletes are motivated to improve their skills and enhance their abilities. Girls Supporting Girls was a movement started in 2013 for female empowerment of one another. Receiving support from other women creates a sense of community and many college athletes have meaningful advice for younger athletes who are beginning to try sports.

Sophie Kadifa (‘21), now plays water polo at LMU.

“Sports is about more than just winning games,” Kadifa said. “It’s about meeting new people, learning to be a part of a team, learning life skills, and working hard.”

While there has been tremendous growth in female athlete participation and opportunity, there is much more work to be done to achieve equity. It is important for students to speak up and know their rights as athletes. Creating change takes time, and is difficult, but if Paly students continue to persevere, change is inevitable and women will achieve the equal opportunity that they deserve.

As Spencer put it, “today, follow your dream. If you want to play in the big leagues, any sport, just do it. Follow your dream.”

Hi! I'm Grace, Editor-in-Chief for Viking's 2023-2024 school year. I am a four-year member of the Paly varsity swim team, and I also played water polo...

Hello All!

I love to play water polo! I love to ski in the snow! I love tacos! Just a word of advice... Don't talk to me until my morning coffee!