The Menstruation Situation

December 19, 2022

A single week has a finite number of hours. For students, the challenge is often fitting everything in: Thirty hours of school; Fifty-six hours of sleep; Sometimes 18 or more hours of schoolwork and studying; On top of this, every four weeks, a large proportion of healthy teens spend over one hundred hours straight bleeding. But not from any sort of cut or wound; instead from the natural process of menstruation.

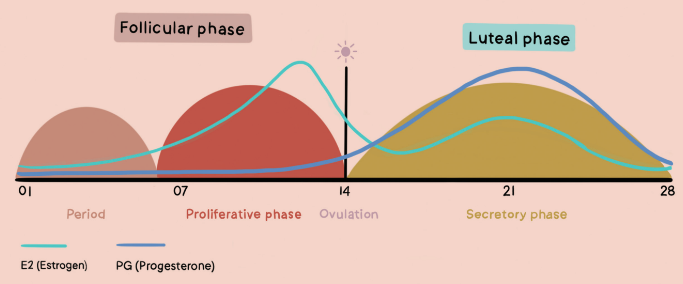

According to UNICEF, around 1.8 billion people on planet Earth have a menstrual cycle. It is regulated by the hormones estrogen and progesterone and typically involves a four-week cycle. During this month, the uterus –– the organ that can house and nourish a fetus –– spends three weeks building up layers of nutritive tissues, which are heavy in blood, for a baby to live on, then one week shedding it out the vaginal canal to start again. During ovulation, an egg is released from the ovaries and travels through the fallopian tubes to the uterus, where it will be housed for three weeks, until the bleeding phase: “menstruation.” If the egg is not fertilized by a viable sperm during this period of tissue build-up, the last week of the cycle is spent shedding the egg, along with the blood, tissue, and nutrients of the uterus’ lining. See our graphic on the next page to see the cycle over the period of a month.

Most menstruators get their first period around the age of 12 and bleed –– on average–– once a month until menopause, the age when the nautrally occuring reproductive hormones decline to the point where menstruation can no longer be regulated and a baby can no longer be grown. This usually begins around age 50 but can depend on a range of factors such as genetics or environmental stress.

Dealing with often over 100 hours straight of bleeding each month, along with the other physical, mental, and hormonal changes menstruation brings, is a major disruption to the daily life of menstruators. To athletes, however, this disruption is even more pronounced. The physical effects of menstruation doubly affect athletes by disrupting their performance, and the mental and hormonal effects add even more stress to their already-busy lives.

But despite all the difficulties of being a menstruating athlete, millions of women around the world do it every single day, overcoming mental and physical challenges brought on by their menstrual cycles.

The physical symptoms of a period most often consist of cramps, muscle and joint pains, headaches, and constipation. As one could imagine, many of these symptoms can affect how an athlete feels while exercising. An anonymous senior at Paly is familiar with the painful effects of periods during play.

“A lot of the times I don’t feel like myself when I’m on my period and I feel like I can’t play to the best of my ability,” she said. “It definitely negatively affects me and doesn’t add any positives.”

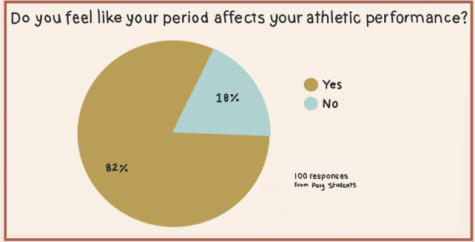

From a survey conducted of over 100 Paly students, it was revealed that 82% of athletes find that period symptoms affect their athletic performance. One of these many athletes is senior cross country and track athlete Grace Corrigan. The rigorous training required in long distance running, which Corrigan participates in daily, demands a lot of her body. Whether it is in the workouts or races, being at your best is required for a strong performance, and the menstrual cycle sometimes prevents this from happening.

“I usually get bad cramps at the beginning of my cycle and it hurts just to stand up and walk around school, so running is definitely hard,” Corrigan said.

Senior soccer player Addie McCarter also feels the negative effects of her period while playing.

“During games I just feel like I get dehydrated faster; I’ll get nauseous faster,” she said. “It’s hard to give it your all when you’re in pain.”

Even elite professional athletes feel the effects of their period.

In the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the marathon runner Lonah Chemtai Salpeter of Israel entered the women’s marathon field with a long list of accolades and recent strong performances. She had won the Tokyo marathon just months before and holds numerous Isreali national records. She was expected to be in contention for a very strong placing in the field of world class athletes.

However, with just a few miles left in the race, her pace dramatically slowed. She quickly dropped from the front pack, and her consistent sub-5:30 mile pace dropped to a slow jog with intermittent walking and breaks. She finished the race in 66th place, with a time of 2:48:31, over 30 minutes slower than her personal best. Later, she attributed this irregular behavior to her devastating period cramps.

However, with just a few miles left in the race, her pace dramatically slowed. She quickly dropped from the front pack, and her consistent sub-5:30 mile pace dropped to a slow jog with intermittent walking and breaks. She finished the race in 66th place, with a time of 2:48:31, over 30 minutes slower than her personal best. Later, she attributed this irregular behavior to her devastating period cramps.

“I felt pretty weak and really tired [and my] cramps did not give me a break from the beginning till now,” Salpeter said in a Facebook post. “With 4 km to go, I really could no longer run.

Even with the negative effects of her period, Salpeter was determined to finish.

“Despite being sad and suffering, I decided to still reach the finish line, not to give up,” she said.

Dr. Craig says that there are some medical methods to help with difficult period symptoms.

“For certain people, [living with their period is] really tough, and they have very painful, prolonged, heavy periods,” she said. “And those are the young women athletes that might use hormonal regulation to help minimize those side effects, like birth control pills, that kind of thing.”

However, hormonal birth control comes with a long list of potential side effects that can harm their athletics, including excess fatigue and weight gain.

“I was recommended hormonal birth control, … but I chose a different medication because I was worried about gaining weight which I think would negatively impact my athletics” anonymous said.

This weight gain can be even more problematic for athletes in weight-regulated sports like wrestling or rowing. Due to the variability in responses to the medication, some wrestlers don’t feel that birth control is an option. Instead, these individuals must face the negative consequences of their heavy period in order not to sacrifice their athletic performance.

For athletes like McCarter and Salpeter, as well as other menstruators, the physical symptoms of having a period negatively impacts their athletics. But for many others, it can be the other way around: their training negatively impacts the physical symptoms of their menstrual cycle.

Female athletes in intense endurance sports, such as swimming and long distance running, commonly suffer from a condition called athletic amenorrhea. Symptoms of Amenorrhea (beyond the absence of regular bleeding) include unusual fatigue during workouts, thin or falling-out hair and brittle nails. Because of a variety of factors –– mainly having low body fat, caused by hormone imbalances, overtraining and underfueling –– the body does not have enough available nutrients to continue all proper bodily functions. It chooses only the most essential. Thus the period, among other things, is excluded.

Dr. Jodie Craig says that this condition occurs for different reasons in different people.

“It tends to be in athletes that are doing a highly aerobic sport, and get down below a certain percentage of body fat and it varies from individual to individual,” she said.

Many female Paly athletes train over 20 hours a week, and their bodies struggle to keep up with this physical demand. Sometimes amenorrhea can be attributed to isolated factors, like low body weight or hormone imbalances, but sometimes it is part of a harmful health condition known as the “female athlete triad.”

This consists of lack of energy due to underfueling (or not eating enough), lack of a regular menstrual cycle, and low bone density. It is a complex condition many female athletes face, whether they are aware of it or not. Because the triad is made up of multiple factors –– with some often being a struggle to recognize, such as disordered eating leading to underfueling –– it becomes difficult to diagnose. This creates a frustrating effect on performance and mental health, as the athlete remains uninformed about what is happening to their body and why their performance is declining.

On top of this, the “female athlete triad” can be part of a larger condition, called RED-S, or “relative energy deficiency in sport.” This can lead to lasting health effects such as infertility or weaker bones, and irregular periods are often the first sign.

According to a study by the National Athletic Trainers Association, 44% of female high school athletes believe that losing their period is a normal part of their training. This common misconception is extremely harmful to young girls’ health. Senior swimmer Alden Backstrand believes there is not enough discussion surrounding the loss of a period

“I feel like [irregular periods] are just so common in the sport [of swimming] that it’s just overlooked and no one says, ‘oh, this definitely isn’t healthy for most teenage girls,’” she said.

Although some might see losing their period as a convenient phenomena –– it makes you cramp-free, saves money that you would spend on tampons, and relieves the worry about staining your cute white pants –– in reality, it is dangerous and unhealthy, especially for teens whose bodies are developing.

If the human body does not have enough energy to have a period, it means it also does not have enough energy to repair bones, regrow muscle, pump blood, or grow hair and nails. Instead, it is working to simply keep you alive while essentially running on an empty tank. Lacking a period can also cause bone fractures or osteoporosis, headaches, acne, and future infertility (without a period cycle, there is no ovulation, causing troubles with getting pregnant).

Dr. Craig emphasizes the negative effects of losing one’s period.

“It’s not a great thing if that happens, because it’s probably your body telling you that you’re down to a fat weight that has become unhealthy for your particular body to maintain its normal functions,” she said.

Another anonymous amenorrheic athlete says that the possibility of future infertility is a cause for worry.

“I am concerned because my doctor told me once that if you don’t get a regular period, it could mean you’re infertile,” she said. “I don’t know if that means I’m infertile, but it’s always a bit stressful.”

Beyond worrying about possible infertility, the athlete also notes that underfueling may play a role in her amenorrhea.

“My period could be irregular if I’m not eating enough; I’ve definitely struggled being a female athlete [and] getting enough calories,” she said.

In addition to these internal stressors of worrying about not getting a period, infertility, or underfueling, athletes with uteruses also face numerous external stressors.

For one anonymous source who plays on a co-ed team, being around men who are generally non-menstruators when the athlete is on her period creates a stressful, uncomfortable environment.

“Not only do they not understand, but it was hard enough to get them to see me as a player and not just as a girl,” the source said. “I know the guys would try to be understanding, but they just don’t understand.”

Periods have been considered “taboo” for a long time, not just around men, but also around other women. Before Title IX In 1972, there was no discussion of periods in sports because women in sports was so rare. Since then, there has been an increase in frankness about periods, but even today, many menstruators don’t feel comfortable talking about their period openly, especially for athletes with male coaches.

“A while ago I had a coach who was very emotionally closed off, so people definitely did not feel comfortable going up to [him about this subject],” said our second anonymous source.

For athletes with coaches like this one (who is not a Paly coach), it can be tough to feel comfortable in their sports environment when one is on their period.

Fortunately, from a survey of over 100 Paly students, the majority responded that they did feel their teammates and coaches created a positive environment for those on their period. However, this positive sentiment is not universally felt; around 30% of respondents instead felt that their team was not a friendly environment for periods.

These negative environments can at times deter athletes from asking for a break or a day off, forcing them to play when they’re not at the top of their game, which in itself can be stressful, irritating, and at times, painful.

McCarter feels that having a female coach makes her feel more comfortable asking for a needed rest due to period pains.

“There’s definitely value in having a female coach, because they understand more of [the period issue],” McCarter said. “With a male coach, I think that it is not often taken seriously to take period-related breaks just because of the stigma surrounding periods and menstrual cycles.”

Even with a female coach and a positive environment, McCarter still feels internalized pressure to play through her pain, especially during games, because of the societal stigma around menstruation.

“It’s fine when it’s just practice and you can kind of take it easy a little bit,” she said. “But for games in particular, I feel like I owe something to the team to give it my all, so it’s hard to recognize when to step down, especially when you’re stepping down because of something that’s so stigmatized. You feel like you’re going to be judged for [taking a break] for that reason.”

In addition to stresses surrounding the team environment and social stigma, menstrual cycles induce stress in many small ways, like the fear of staining while wearing white bottoms for uniforms.

In fact, some women have protested the international tennis tournament Wimbledon, where athletes traditionally wear all-white outfits to play, because of this issue.

British tennis doubles athlete Alicia Barnett addressed the stress of having to play wearing white when she is on her period.

“I do think some traditions could be changed,” she told a news agency. “Having this discussion [about optional dress codes] is just amazing.”

Other professional athletic teams are also taking on this issue. Just a month ago, female soccer players in England began voicing their concerns about wearing white shorts as a part of their soccer uniform. Manchester City, West Bromwich Albion and Stoke City are among the teams who are switching the color of their players’ uniforms to make their playing experience less stressful when they’re on their period.

The captain of the West Bromwich team is grateful for the change, and that her and her team’s concerns are being listened to.

“Representing the club professionally and looking smart in the kit is really important to us,” she said to the Independent.ie. “This change will help us to focus on our performance without added concerns or anxiety.”

McCarter, a fellow soccer player, says this accomplishment is a big step in overcoming the stigma surrounding periods.

“Little stuff like that: creating conversation around [periods] and not viewing them as something that’s bad or shameful or embarrassing, is really important,” she said.

Many feel that just because periods being taboo is widespread, doesn’t mean there isn’t something to be done about it.

“It’s something that’s stigmatized by our society and it’s hard to change,” McCarter said. “[But] it’s a learned thing to be uncomfortable around periods, and it’s something we’re not supposed to talk about because it makes people uncomfortable.”

Dr. Craig acknowledges that discussion around periods is crucial.

“The more we normalize a completely normal body function, the more people will be understanding,” she said. “And then hopefully if more people will talk about it, everyone will benefit.”

Professional athletes like Salpeter agree. After the difficult Olympic marathon where she competed on her period, she hopes to spread more awareness and continue the conversation that athletes suffer from the effects.

“I think we really need to normalise the conversation around being female athletes,” she said in her Facebook post.

Something that is most frequently stigmatized around periods is the emotional changes linked to hormone shifts. Women all around the world are subjected to the ignorant and insulting comment of, “oh, she’s on her period” upon expressions of anger or frustration.

While menstruation does lead to chemical changes in one’s body, they generally don’t create new emotions, they just heighten already existing ones. For this reason, among others, the above comment and similar ones are not only remarkably dismissive of women’s emotions as well as also being baseless as an ‘explanation’ for women acting in ways contrary to what people perceive as normal.

In fact, people without periods have hormone shifts too. According to Healthline, people without uteruses have a peak in testosterone in the morning and a fall in the evenings.

“There are known hormonal fluctuations that can affect your mood… both in men and women, actually,” said Dr. Craig. “Testosterone levels will affect men’s moods, as well as estrogen and progesterone levels in women.”

To end this stigma, it is essential that people are educated about the actual events in a menstrual cycle. Hormones like estrogen and progesterone peak during ovulation. In the phase in the cycle after ovulation, called the luteal phase, both these hormones begin to fall. Then there’s a second smaller peak as progesterone rises, peaks, and then drops again. The rapid rise and fall of all these hormones often affects neurotransmitters in our brains, namely leading to irregular levels of dopamine and serotonin. See our graphic to follow the levels of chemicals.

These irregular levels of hormones can heighten emotions –– namely stress –– in some menstruators.

But beyond these hormones, Dr. Craig emphasizes that the pain of having a period creates negative feelings and can damage one’s mood as well.

“Less attention is paid to how it affects your mood in the sense that you’re bleeding,” Dr. Craig said. “Especially for really young girls who are getting periods for the first time, [there is] fear or anxiety that comes along with that. Also for a large subset of the population, having your period is painful. … And when you’re in pain, it affects your mood. That’s true even when people are injured or have a headache or have a sore throat. Even the non-hormone based side effects of having your period affect your mood.”

So, female athletes with athletic amenorrhea –– those who should menstruate but are unable to –– worry and stress over health concerns about not getting their period, and athletes who menstruate regularly worry and stress about getting their period; how this will affect performance, how their will tell their coach, what they will wear. Additionally, regular menstruators face the inherent stress that comes from the hormone changes of having a period.

Stress, for both those with amenorrhoea and regular menstruators, is unhealthy. In response to stress, the body can interrupt the release of estrogen and progesterone. For those already menstruating, enough stress can stop a period, and for those with amenorrhea, stress will be an inhibitor in helping them regain their period.

Thus, both a lack of menstruation and a period itself cause stress. This can in turn lead to a lack of menstruation, which causes more stress, which makes athletes more likely to lose their period. The vicious cycle continues.

But for one’s body, it is best to have a healthy period cycle. If you’re missing your period now due to your sport, there are many ways to return to a normal cycle. You can cut back on the intensity and frequency of your workouts, and make sure to take needed breaks.

Dr. Craig assures athletes that their periods will likely return.

“If you’ve gotten to [a healthy period before your sport], and then you’ve had amenorrhea from exercise, then usually, there’s a really good chance that you’ll get it back after your sport or your high intensity exercise is over,” she said.

The aforementioned swimmer Backstrand also stresses the importance of listening to your body, especially in her sport.

“Just swimming for hours and hours isn’t going to be that productive,” senior Alden Backstrand said. “You need to sleep and you need to eat, and you need to have a social life and be with your friends. [Irregular periods] shouldn’t be common for girls. To just not get their periods because they’re over exercising is not healthy.”

Even with the stress, anxiety, and stigma that surround the monthly action of shedding the inner lining of the uterus –– or not being able to –– a period can still represent something inspiring. Periods can represent strength and beauty. Periods can represent the empowerment, the resilience, and the power of women, especially female athletes. McCarter takes pride in this.

“I think [periods] are empowering for women because we are in pain and this does suck,” she said. “But we are still able to perform; we still do it.”