Despite coming from a challenged home, Aaron Hernandez was a promising young man growing up in the small urban town of Bristol, Connecticut. After playing football at the University of Florida, he won the John Mackey Award, given to the best tight end in college football, and he made the conference honor roll during his sophomore year. As a result of his stellar college play, he was drafted in the 4th round of the 2010 NFL draft, with high hopes for his future.

Then, out of the blue, during the offseason after his third year in the league, he was convicted of first-degree murder of another semi-professional football player. Following his suicide in prison, doctors examined Hernandez’s brain and diagnosed him with stage three (of four) CTE.

CTE, or Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, is a degenerative brain disease caused by repeated head trauma; symptoms include confusion, memory loss, aggressive behavior, and suicidal tendencies. It causes sharp attitude changes, and it is a progressive and deadly disease that can only be diagnosed post-mortem.

In 2002, Doctor Bennet Omalu discovered CTE by examining the brain of former Pittsburgh Steelers Center and Hall-of-Famer Mike Webster, who passed away after suffering a heart attack. Before his death, Webster showed troubling symptoms such as memory loss, aggressive behavior, dementia, and more. Upon examination of his brain, and other former NFL players with similar symptoms, he discovered what would eventually be known as CTE.

Athletes in high-contact sports, especially football and hockey, are prone to getting major head injuries. Hernandez was believed to have suffered repeated head trauma from the time he started high school football all up until his tragic suicide in prison. After an autopsy of his brain, doctors found a severe case of CTE in Hernandez; the damage suffered was comparable to many former NFL players in their 60s.

Aaron Hernandez is just one of the many ex-athletes who have been affected by CTE and brain injuries. Unfortunately, the majority of victims go undiagnosed and unrecognized, making CTE all the more dangerous for athletes in extreme contact sports. Hernandez was one of at least 345 NFL players to be diagnosed after death with CTE.

According to the data released by the NFL, there was an 18% increase in concussions in 2022. Psychology and Neuropsychology specialist Dr. Johnny Wen at the Torrance Memorial in California conducted neuropsychology checks on retired football players in conjunction with the NFL.

“Each team in the professional league (or even the collegiate level) have professionals right there with their team who are there to evaluate them,” Wen said. “It’s not just football; in race car driving, they have doctors there; soccer, they have doctors there.”

As a result of the increased number of head injuries and recent research on CTE, sports teams at all levels are beginning to implement CTE prevention tactics.

“I do think that there are a lot of changes that have taken place, people are taking a lot of precautions now,” Wen said. “If you do suffer some type of injury or suspect these types of injuries, they will have you undergo evaluations, and there are clinics now set up, they’re called Immediate Post-Concussion Assessments and Cognitive Testing (ImPACT).”

CTE can lead to devastating symptoms. The National Library of Medicine states that CTE results in a steady decline of memory and cognition, as well as depression, poor impulse control, aggressiveness, Parkinsonism, and eventually dementia.

“Over time, [people with CTE] may have decreased attention,” Wen said. “They may have a more difficult time regulating their emotions and managing their mood.”

One unsettling fact is that one symptom of CTE aided in its discovery and research: CTE can increase suicidal ideations, and many of the brains with CTE that are studied are donated by young suicide victims.

CTE is known to get worse over time, and it cannot be definitively diagnosed until after death in a brain autopsy. The most common causes of CTE are repeated head injuries. If your brain doesn’t have enough time to rest from a serious head injury, receiving a second head injury can have a devastating effect. The Paly sports trainer, Justine Iongi, also known as Ms. E, explains the dangerous effects of secondary concussion injuries.

“There’s a thing called secondary impact syndrome,” Iongi said. “If you sustain another concussive injury to your brain, what happens is it hasn’t fully healed from the first one, so that can put your brain into metabolic stress. It can become fatal and you can deteriorate really really fast.”

In a recent study, the Spaulding Rehabilitation Organization examined 631 brains donated by former football players. Only 29% of the brains showed no signs of CTE, while 26% of the brains had CTE stage 1 or 2, and 46% had CTE stage 3 or 4.

To put those numbers into context, a 2018 study by Boston University of 164 brains donated by women and men showed that only one showed signs of CTE – around 0.6 percent. The one brain that did show signs of CTE was an ex-college American football player.

“I don’t want to minimize the head injury and say they don’t have problems,” Wen said. “But what I’m saying is that not every player has CTE. And a lot of times, we have to look at other factors.”

Factors can include, but are not limited to, a family history of alcoholism, dementia, or mental health. All of these factors could make you more vulnerable to CTE.

CTE is impossible to recognize since it cannot be diagnosed concretely until after death. Still, those showing signs of CTE are beginning to gain increased attention as people start recognizing the dangers of contact sports and the long-term impacts they can have on one’s health. CTE is not a brain disorder limited to only American football; it extends to a plethora of high-contact sports, such as ice hockey, wrestling, and many more.

According to Amy Woodyatt and George Ramsay of CNN, many wrestlers at the Olympic level have had struggles with second head injuries, one example being dominant wrestler Helen Maroulis. She is a powerful force in wrestling, winning numerous world and regional championships and an Olympic gold medal in Rio in 2016. However, following a series of concussions that impacted her career, she reportedly began struggling more with her mental health, to the point where she was admitted into a psychiatric ward treatment facility due to suicidal thoughts, causing her to miss the Tokyo Olympics. Fortunately, she is making her recovery and has her eyes set on Paris. She is also vocal with fans about her journey with her mental health struggles and encourages those who need it to seek help to recover, sharing her voice in a documentary, “Helen | Believe.”

Another unseen and overlooked sport that presents risk is ice hockey, a sport demanding and relying on heavy physical contact. A preliminary study by Boston University showed that each year of ice hockey play may increase the odds of developing CTE by a staggering 23%. Furthermore, they found that each additional year of play was associated with a 15% increased chance of a person progressing to the next stage of CTE.

In another study done by Boston University, they looked at 152 brains of contact sport athletes who died under the age of 30, and the results were startling. They discovered that 41.4% showed symptoms of CTE.

Concussions, second-head injuries, and the risk of CTE are not limited to professional or college-level sports; the risk at the high school level is very real and not solely limited to American football.

Two-year varsity baseball player Dexter Cleveringa has experience with concussions in his more than five years playing catcher for his club and school teams.

“Concussions have been fairly and unfortunately constant throughout my time playing baseball,” Cleveringa said.

As a precaution to prevent further injuries, Cleveringa was forced to take time off of the sport and miss a part of the season. Thankfully, helmet technology and concussion procedures help to mitigate, if not stop, the effects of hits to the head.

“Although I’ve had a bunch of concussions over the past 4-5 years with baseball, none have been super serious or detrimental to any of my academics or extracurriculars,” Cleveringa said. “Most were related to a baseball hitting my helmet in some way, whether that be a hit by a pitch or a foul tip that hit my catcher’s mask.”

School administration attempts to accommodate students with concussions by striking a balance between an athlete’s playtime and recovery. However, time spent off the field limits the athletes and makes the student-athlete balance all the more difficult.

“I had to figure out how to manage school work along with that,“ Cleveringa said. “The administration was very helpful during that time and was able to accommodate me with things I was having trouble with.”

Paly senior and track athlete Victoria Eberle was forced to give up contact sports after suffering two concussions. These concussions, especially her second one which she endured in eighth grade, affected her performance in school and everyday life.

“When it comes to concussions, you can’t really focus on what you are doing,” Eberle said. “You miss out on a lot of tests, and it is harder to understand things and learn new concepts.”

After undergoing the necessary precautions, the effects of a concussion can be mitigated and lessened, allowing most to completely return to athletics after sufficient time off to prevent second head injuries.

“I wouldn’t say that [concussions] ever affected my confidence in sports or my enjoyment playing them,” Cleveringa said.

Furthermore, there are plenty of side effects of suffering repeated head injuries.

“After my second concussion, I experienced a lot more migraines and I ended up having to go on medication for my mental health as well,” Eberle said.

However, if concussions are disregarded or ignored, they can have much more severe long-term effects, like CTE and its symptoms.

“People who suffer consistent head injuries can be suicidal or get depression, and really impact your personality,” Eberle said. “I am grateful that my concussions have not affected me in ways that I know they could have.”

Although progress has been made concerning concussions in high school sports, there is still much to be done to protect athletes in their sports.

“The current types of helmets really only protect surface-level injuries; when the helmet gets hit with a strong force, the padding helps with some of the absorption, but it doesn’t stop your brain from rattling around,” Cleveringa said. “Two-piece catcher’s masks are definitely something that helps with this because they can fly off and absorb the force elsewhere without transferring it to your head.”

Despite safer alternatives like the two-piece mask, many high school leagues don’t allow them as they don’t provide enough ear protection.

“However, league regulations prevent the usage of these [two-piece] helmets, which is a shame,” Cleveringa said. “It’s pretty hard to come up with new helmet technologies, but it also kind of sucks that they can’t use the existing alternatives.”

Attempts are being made in the law to protect athletes from CTE. Recently, in an effort to mitigate head injury risks for young athletes, Kevin McCarty proposed Assembly Bill 734, proposing a ban on tackle football for ages twelve and under. Governor Gavin Newsom later vetoed the bill due to intense pressure from parents who believe tackle football is crucial for their child’s social and physical development. Football culture is deeply ingrained in American culture, as the idea of flag football being a safer alternative for young kids is often shot down.

However, Newsom agreed to work with legislators to reinforce youth football safety while respecting the parent’s rights.

“I am deeply concerned about the health and safety of our young athletes, but an outright ban is not the answer,” Newsom said in a statement.

Wen believes that the parents will need to take the initiative in regard to safety.

“We need to have safety precautions in place if we are going to allow this, but I think it’s all going to really come down to the parents who are willing to allow their child to play these types of contact sports,” Wen said. “Now, remember, just because you have a child who has contact [in their sport], contact doesn’t mean they’re going to have problems.”

Proponents of the bill argue that flag football will teach children the fundamentals of football while keeping children out of harm’s way, citing the NFL’s decision to change the Pro Bowl to flag football. In the last few years, the NFL switched the Pro Bowl (an exhibition game featuring the league’s biggest stars) into a non-contact flag football game to alleviate any risks of injuries for the players that might needlessly impact their seasons and careers.

A study done in 2019 compared youths from the ages of six to 14 playing tackle football and flag football. Tackle football athletes had 14.67 times more head injuries compared to flag football athletes. This study may be stating the obvious, but by playing flag football, they’re creating the same environment to learn the groundwork of football without the added risk of injury. In addition, athletes playing tackle football were 23 times more vulnerable to high-impact tackles per football exposure.

This study demonstrates that youth athletes playing tackle football are more likely to experience a greater number of head impacts and are at a markedly increased risk for substantial hits compared with flag football athletes.

NFL and contact sports are ingrained in American culture and are not going away anytime soon. The NFL has issued limited aid in preventing CTE or treating retired players, although they do have a hotline for NFL players, coaches, or families to call in a crisis.

Upon Hernandez’s arrest in June of 2013, NFL spokesman Greg Aiello put out a statement about the situation on the NFL’s official website.

“The involvement of an NFL player in a case of this nature is deeply troubling,” Aiello said in part of his statement online.

The NFL has taken general injury prevention measures, such as the recent requirement to have natural grass fields and new helmet technology to reduce the effect of blows to the head. Although the NFL acknowledges a “potential association” between playing football and CTE, advancements in the study of CTE and its prevention have been limited, likely due to the lack of diagnostic accuracy in current science.

Unfortunately, physicality and heavy contact are the essence of football. In 2021 alone, 187 concussions were recorded throughout the season.

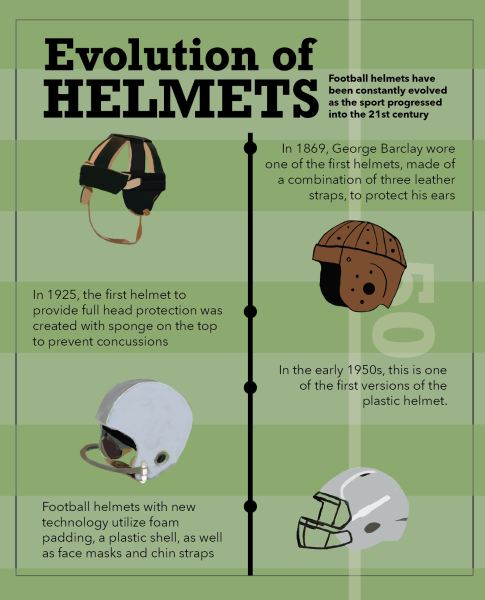

However, over the years, helmets have become more advanced, reducing the number of concussions and making the players safer. Yet, until 1943, the NFL did not require helmets in their games. Throughout the 1900s, these helmets weren’t meant to be protective if at all. Football helmets have gone from just leather helmets to the modern barred ones we see today.

Studies have shown that wearing helmets can reduce the risk of head injuries by up to 50% and severe head injuries by 69%. But this is generalizing every position; running backs, on average, get hit 30 times a game with forces up to 10+ G. Just three G’s is the force that astronauts experience when leaving Earth. One example of this is Christian McCaffery, a running back for the 49ers, he runs on average 20 miles per hour. When tackled, all of that speed and momentum abruptly stops, exaggerating the blow.

Football, being a contact sport, can’t change, so receiving all of the protection you can get can greatly reduce the damage done by these rigorous hits. The NFL has instituted many rules and regulations to help prevent head injuries. But are all of these rule changes and regulations creating a difference? The answer, as of now, is no.

According to the NFL, in just this recent preseason, 58 concussions have been reported. And often, we see a downward trend of concussions, with the 2019 and 2020 seasons having 224 and then 172 concussions, respectively. However, just in 2022, the number of concussions jumped straight back up with 213 concussions.

So, what has the NFL learned? In 2016, the NFL officially acknowledged a connection between playing NFL football and CTE. Since then, they have been constantly investing in research to produce safer helmets for the players. Although the NFL and football associations have been pushing to make the game safer, the number of concussions doesn’t have a trend in one way or the other.

“Concussions are injuries that many people consider to be just another part of the football experience, but they’re not to be ignored,” Jennifer Del Ross, MPT and Concussion Specialist at Chester County Hospital, said.

While perhaps Governor Newsom is correct, and a ban on contact sports is too far, the startling new research on CTE reveals that contact sports and concussions should be taken far more seriously than previously considered. If you get a head injury, take a break until you’re fully healed. It could mean more for your brain than you know.