Rollin’ with the punches

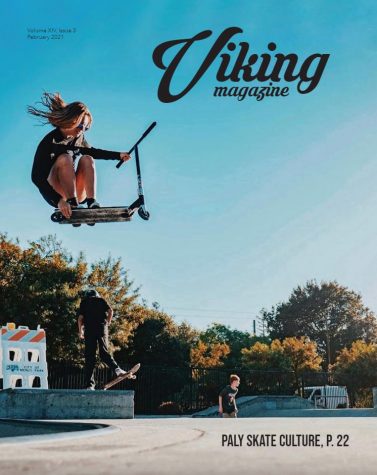

Laura Mann and her teammate work together to keep the other team’s jammer from getting through the pack.

November 12, 2014

When someone hears the word skating, they often picture a graceful dancer moving around an ice-rink. Others may imagine people rollerblading. However, those associated with the sport of roller derby know a whole different picture, complete with constant injuries and extreme physicality. Bouts, jammers, pivots, blockers–these words may sound foreign to an average person, but they are all central parts of this aggressive sport.

Besides the use of skates, roller derby is about as different from any other form of skating as it can get. In roller derby, two teams compete instead of performing for an audience. The teams race around a circular track on roller skates and each works to score points by lapping as many opponents as possible.

Although roller derby is usually portrayed as a women’s sport, men can skate as well. Since the sport’s revival in the early 2000s, there have been three main types of roller derby leagues: all-female, all-male and mixed-gender.

Now, the sport has spread across the world, with leagues in Europe, Japan, Korea, Australia, South America and even the Middle East. In 2011, the first roller derby World Cup was played in Toronto, Canada, with thirteen participating countries. In December of this year, the second World Cup will be played in Dallas, Texas. 30 countries are expected to make an appearance at the event.

Current Bay Area Derby Girls All-Star skater Laura Mann skated in the first World Cup for Team USA. She is preparing for this year’s competition along with the 19 other skaters on the American World Cup team.

Mann first started skating about eight years ago, when she lived in Albuquerque, N.M. She was working as a photojournalist intern at the Albuquerque Tribune when a story written by one of her colleagues exposed her to the sport. Given her background in ice skating, the transition to roller derby was easier than it may have otherwise been.

“Someone else was doing a story on [roller derby and] I was helping [to] edit the photographs,” Mann said. “I looked at them and I was like ‘hmm, I could probably do that,’ so the next summer I…contacted a league and started skating…I ice-skated growing up for about 11 years so I had a skating background, just not on wheels.”

Now a veteran of the sport, Mann described roller derby as being simultaneously offensive and defensive.

“It is a full contact race on roller skates, but only one person from each team is actually trying to race around,” Mann said. “It is basically five on five…It’s offense [and] defense at the same time. [You] try and stop the other team from passing you.”

Roller derby is played in two thirty-minute periods. Each half consists of short matchups, which are called jams. There are three main positions: jammers, blockers and pivots. Jammers are the skaters who are trying to race around the track and get by the blockers on the other team. Their objective is to pass as many of the opposing skaters as possible during the two-minute jam. They wear two stars on their helmets to distinguish themselves from the other skaters on the track. Four of the five skaters on a team are blockers. They attempt to block the other jammer from getting through and blocking other opponents to help their jammer get through. One of the four blockers is known as the pivot. Pivots wear a striped cover on their helmet, and they can become a jammer if the jammer passes them the cover with stars on it. Each jam ends either when the two-minute time limit runs out or when the lead jammer, the one who initially broke through the pack of blockers first, chooses to end the jam at a more strategic time.

The sport was invented in the United States in the 1930’s by Leo Seltzer. Initially, the sport had no point system and instead was about endurance in the marathon-like races. Roller derby began as a speed race where the only severe contact between skaters occurred when one tried to pass another. However, in the late 1930s, Seltzer was encouraged to allow maximum physical contact between skaters to make the sport more entertaining for fans and since then the sport has transformed.

With this change came a key component of the sport: physical toughness. Every bout is full of lots of blocking and pushing. For Mann, a blocker, she was intrigued by the physicality and violence of the sport.

“I really like the aspect of being able to hit people,” Mann said. “When you see someone that you want to hit that’s in your way on the other team and [you’re] able to go up to them and hip check them as hard as you can legally and possibly knock them down, I think that’s really fun.”

Even though the sport is extremely physical and bumps and bruises are very common, Mann has only been seriously injured once.

“My very first season, I got hit into a cinder block wall because our venue wasn’t a very safe,” Mann said. “I got hit into that and my knees both splayed in and I ended up tearing my MCL in my left knee. But [I didn’t need] surgery, just 12 weeks recovery….I’m convinced it was the brick wall’s fault and not the actual [sport].”

In addition to the brute nature of the sport, the required mental toughness can pose a challenge. For Mann, she believes the key to doing well is to stay calm.

“[You have] to be in a really good place in your head to not have anxiety and not freak out,” Mann said. “Sometimes you will be playing a team and you look at the scoreboard and you are not winning, [and] you can’t let that get into your head.”

To prepare herself mentally, Mann goes through a process where she envisions a positive memory of herself.

“I have a weird little [thing], it’s recalling sports events of the past,” Mann said. “I had a sports psychologist that had me lay down and visualize a time that I did really well and I visualize myself ice skating and winning.”

On top of visualization, Mann has another ritual that she does before every bout to get in the right mindset and play her best.

“I click my wrist guards together before the game and [absorb]…that feeling of the crowd and the smells and everything,” Mann said. “It kind of resets [my mind].”

Besides the mental rigor of playing in games, there is also a difficulty associated with the mental component of pushing herself to practice.

“The motivation to go to practice [is one of the hardest parts of skating],” Mann said. “Practice is fun once you [are there], but sometimes when you’re tired and [it’s] after work [it’s hard] to get the motivation to go.”

All the difficulties that skaters go through together encourage them to respect each others’ abilities and they push one another to get better.

“My roller derby role model is… actually one of my teammates, Fallen Angel,” Mann said. “She doesn’t come from a skating background and [I’ve] just [watched] her work hard over the years. She’s been skating almost as long as I have, but she has definitely surpassed me in her abilities. And her drive off the track [is impressive]…she goes [to the gym] almost every other day. And she has a full time job so I…don’t know how [she goes] to work and [gets] up at 6 A.M. and then [has] the energy to go to practices.”

While there are a lot of challenges that the sport entails, Mann enjoys many components of roller derby and especially appreciates the community that the sport has created worldwide.

“The community aspects of it [are one of my favorite parts of skating],” Mann said. “I’ve skated in something like four other countries so far and…I’ll put something out on Facebook…and within an hour someone’s picking me up from the train station [and] putting me up at a house with my own room. It’s happened over and over again, all through Europe and China and…in Mexico…just people accept you [because] you play roller derby.”

Another central part of the roller derby community is the emphasis on traditions and customs. Skaters still use the original style of skates with four wheels, two on each side of the skate. They have also continued the tradition of using fake names that tend to sound intimidating and have some sort of pun attached to them.

“Back when roller derby was first starting in the 20s, people were just choosing handles, it was more theatrical,” Mann said. “It got started from that kind of culture of having a stage name. People wanted to carry on that tradition, same with having the quad skates.”

Stage names were not the only theatrical part about roller derby when it first began. Each bout was planned ahead of time with hits and injuries that would make it as entertaining as possible for spectators.

“It was actually very staged back in the day,” Mann said. “It would be like ‘Okay, I’m going to elbow you and then you’re going to fall’ and now it’s not like that anymore in the current incarnation of roller derby started by the Texas Rollergirls.”

Now, many skaters are trying to get more recognition both for themselves as athletes as well as the sport as a whole. With that comes a new trend of using one’s real name instead of a fake one. However, this change is not accepted by everyone.

“The trend nowadays is people using their real names try to legitimize the sport, so it’s not seen as just girls trying to beat each other up in fishnets, but actually athletes that train,” Mann said. “Some people are totally on board with [that] and others are [not] but I don’t have an opinion either way. I…go by my derby name [for the] Bay Area Derby Girls…but then on Team USA I go by my real last name.”

If a skater decides to use a stage name, the name they choose usually means something special to them. References can be anywhere from vague to blatantly obvious.

“Picking a roller derby name is very personal,” Mann said. “Some people pick them because of a band they like or a comic book or some kind of reference [like] that.”

Beyond the traditions that roller derby brings, Mann also finds joy in the competition part of the sport. When Mann started skating, she was on Duke City Derby, a team in Albuquerque, N.M. When she felt she wanted to be challenged more, Mann decided to move to a town with a better team.

“I skated [a] season with them [Duke City Derby] and then I realized that they weren’t as competitive and I really just wanted to play; I wanted to be challenged,” Mann said. “Instead of being one of the best skaters on the team, I wanted to be not the best skater so that I could strive, to have a goal to beat someone. So, I moved to Denver where I skated with the Rocky Mountain Rollergirls.”

Mann moved to Denver in 2010, and the move helped her career. During her first year on the Rocky Mountain Rollergirls, her team won the Hydra, a trophy that has been awarded annually to the number one woman’s flat track roller derby team in the world every year since 2006.

“Winning the Hydra, the trophy that everyone is vying for all year…. that was definitely a highlight, something I wanted to do since I moved there,” Mann said. “Basically I told my teammates back in Albuquerque ‘I am moving to win at roller derby, I’m sorry’. They were like ‘What do you mean win at roller derby?’ And I was like ‘Just watch.’”

Instead of peaking with winning the Hydra, Mann’s career has continued to progress. After playing with the Rocky Mountain Rollergirls for three seasons, she came to San Francisco to skate with the Bay Area Derby Girls. She has now skated in the Bay Area for two seasons.

These past years have been busy, as Mann skates almost completely year-round. Mann’s regular roller derby season starts around March, with tryouts for the Bay Area All-Star team taking place in February. Bouts can run until about September, and the season finishes with tournaments that lead to the Women’s Flat Track Derby Association (WFTDA) championships. Following the season, since Mann is on the National Team, she prepares for the World Cup, which takes place in December.

The long seasons add up and can prevent some skaters from holding normal or full-time jobs. Mann, a self-proclaimed lady of odd jobs, has bounced around between careers. She currently house-sits, pet-sits and guest coaches roller derby teams of all ages. Some of her teammates have had better luck with their professional lives outside of skating. Mann has a few teammates who are teachers, some who are Information Technology workers and even one who is a contractor.

Roller derby can also affect skaters’ personal lives. Mann originally moved to the Bay Area with her husband. When he moved back to Albuquerque, she stayed behind to continue her skating career with the Bay Area Derby Girls. The distance has been difficult for Mann.

“I have been mulling over [whether to keep playing] the past few months,” Mann said. “I do have to go home to be with my husband in Albuquerque after this season. It has been a hardship for commute. I haven’t had a home since he has moved. I just move from house to house every couple nights. It’s a little rough.”

Even though moving back to Albuquerque would reunite her with her husband, it would not be without disadvantages. One thing that would make the move harder is the transition to a lower-quality skating team. Mann does not know what this would mean for her skating career, or even if she would continue playing.

“I don’t know if I can skate in New Mexico just because right now we [Bay Area Derby Girls] are number two in the world and Alburquerque is 70th or 80th, so it would be really hard to make that jump,” Mann said. “I don’t know what my future holds. I might try to come back here after my next season. I might try to go back to my old team in Denver.”

Whatever Mann decides to do with her future, she has accomplished a significant amount with her athletic career–winning the Hydra, playing for the second best team in the world, and making the U.S. Olympic team for the second time. With an athletic experience that very few people can relate to, she has been exposed to a culture of skaters that she never would have known about had it not been for that article she worked on eight years ago in Albuquerque. Regardless of the next step in her life she will always have the memories and the lessons that roller derby has given her. <<<