Pain Killers

Opioid use in athletics has a long history; athletes can be prescribed opioids because of injuries or after surgery. Although painkillers can help athletes cope with pain, they are easily abused. Some sports organizations are not careful when they prescribe opioids to their athletes and many athletes have taken advantage of this disorganized system, making them vulnerable to addiction. Intense regulation is needed to guarantee their safety.

January 9, 2020

The story was almost too good to be true.

Well, not good–it stemmed from the unexpected death of a player, a death that rocked the MLB and its fans.

But it certainly had a storybook ending.

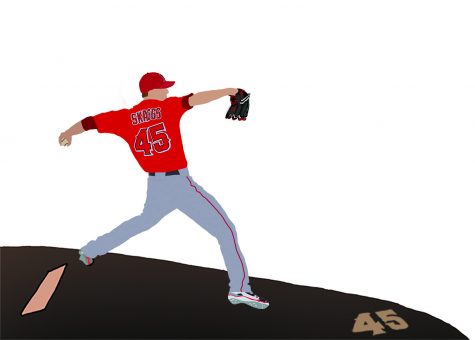

On the first home game after the death of Tyler Skaggs, the Angels’ pitcher who died at 27, his former team delivered perhaps the most iconic memorial game of all time. And it just so happened that the game fell on the night before Skaggs’ birthday–what would have been his 28th.

Each teammate’s jersey bore No. 45 and Skaggs’ name. One of those jerseys was framed and brought onto the field before the game, mounted proudly on a canvas stand. Later, at the game’s end, the mound would be covered in that same jersey, as each of the Angels players removed their jersey and laid it onto the ground in a vibrant red mosaic.

The Angels pitched a no-hitter that game, one of the most coveted feats in baseball, and won 13-0. The victory looked effortless. The Angels looked flawless.

And after the game, the unbelievable details began to surface.

Before the memorial game, the last no-hitter thrown in California fell on July 13, 1991. Skaggs was born that same day–that same year. And the Angels scored seven runs in the first inning, finishing with 13 runs and 13 hits: 7-13.

It was only the 11th no-hitter in Angel’s history. Skaggs, a Los Angeles native, had worn No. 11 at Santa Monica High.

Mike Trout, too, hit a home-run. He swung at the first pitch thrown at him, uncharacteristic for the normally-reserved slugger. But the swing paid off to the tune of a two-run bomb that sailed 454 feet over the wall. 454, of course, is a palindrome of Skaggs’ jersey number.

It was a surreal night–touching, tragic, simultaneously difficult to watch and impossible not to. It was exactly the kind of night that the Angels wanted in order to honor their late pitcher. When they pitched a no-hitter, it felt like Skaggs had pitched it. When Trout homered deep, it felt like Skaggs had swung the bat. That was the kind of send-off that a player of his caliber deserved. The Angels had done him right.

But then details of his death surfaced.

Skaggs had died alone in his hotel room. The organization may have felt the need to smooth over the details of his death, but Skaggs did not suffer an unexplainable tragedy, a young death characterized by a mysterious illness.

The circumstances of his death were crystal clear. Tyler Skaggs died alone in his hotel room after choking on his own vomit, his body’s last-ditch effort to purge the deadly mix of oxycodone, fentanyl, and alcohol he’d ingested.

But this wasn’t an isolated incident; The Angels’ public relations official, Erik Kay, openly admitted to supplying Skaggs with drugs for years. He also ceded that two team officials knew of his drug abuse, long before that fateful night in his hotel room.

So why didn’t an organization which expressed such post-mortem grief and compassion just take precautionary measures before the entirely preventable tragedy even occurred? To understand this, you have to go back, before Skaggs was even born, to a little-remembered New York City celebration in 1986.

The scrappy New York Mets were led by young superstars Darryl Strawberry and Dwight “Doc” Gooden, who played right field and starting pitcher, respectively. Thanks to the help of a now-famous error by Bill Buckner in Game 6, the Mets would go on to defeat the Red Sox in seven games and take home their first title since 1969. From the outside, it looked like there was a future dynasty in the making. But on the inside, there were larger problems that were unresolved.

Cocaine usage throughout Major League Baseball in the 80s was widespread, affecting many superstar players. Gooden, the star pitcher of the miracle Mets, was a prime example. A first-round pick of the New York Mets in 1982, Gooden quickly rose to stardom, winning Rookie of the Year in 1984 and Cy-Young in 1985. But as his talents became apparent, his addiction grew worse. His rock-bottom came on the day of that New York celebration, a parade of his team’s accomplishments.

While his teammates were celebrating amongst all of their fans, Gooden was in the slums of Manhattan doing cocaine with delinquents. He would test positive for cocaine in 1987, and undergo rehab and multiple times in an attempt to come clean. Although he pitched in the MLB for 13 more years, he would never return to the level of dominance that he displayed in his early years.

His personal life post-retirement has been troubled by numerous arrests, with him most recently being arrested for driving under the influence in July 2019. Whilst some players have escaped their previous struggles and vices, the Doc hasn’t been so lucky.

Following the MLB cocaine epidemic of the 1980s, a new problem emerged: painkillers in football. The precedent set by baseball organizations, who did little to curb their players’ ability to abuse drugs, encouraged NFL teams to do the same.

The soreness and chronic injuries that had previously forced players to miss many games at a time could now be ignored, and teams loved it. Painkillers such as vicodin, fentanyl, and oxycodone were mass-purchased by teams, and they were made easily available to players.

Kyle Turley, a former offensive tackle for the New Orleans Saints, used his testimony in front of the House of Representatives to help illustrate the problem currently plaguing the NFL. He noted that some doctors perpetuate the problem by prescribing opioids in large quantities, and gave an example of a doctor offering to sell him 10,000 Vicodin pills.

Time and time again, athletes are forced to endure physical and mental pain in order to compete in their desired sport. Opioids are the ideal solution for many of these problems because the pain that some athletes endure is unimaginable. They allow athletes to escape their pain, but with unforeseen costs. Addiction and overdoses are a direct result of opioid use, yet athletes are willing to risk their careers in order to relieve themselves of pain.

Athletes like Tyler Skaggs and Dwight Gooden are simply microcosms of the underlying issue of drug abuse in sports. There are many more athletes with stories to be told, the true victims of this willed ignorance.

Although many players became addicted to painkillers after consistent usage, Calvin Johnson was one of the lucky athletes that did not suffer from addiction even though opioids were casually available through his professional sports team. A second pick overall in the 2007 draft, Johnson carried out his career as a wide receiver for the Lions and eventually retired in 2016 at the young age of 30 because he was frustrated with the sport.

In an interview with Sports Illustrated, Johnson revealed the opioid abuse occurring during his career with the Lions.

“When I got to the league, [there] was opioid abuse,” Johnson said. “You really could go in the training room and get what you wanted. I can get Vicodin, I can get Oxy[contin]. It was too available. I used Percocet and stuff like that. And I did not like the way that made me feel. I had my preferred choice of medicine. Cannabis.”

Like a lot of professional football players, Johnson suffered major injuries during his career including, concussions, back issues, and ankle problems. To cope with the pain, Johnson smoked cannabis after every game.

Although it is not clear if the greater Detroit Lions organization knew about the supplying of opioids to their athletes, the fact that opioids were so easily accessible to Johnson through the Lion’s training room speaks to a greater leniency towards the abuse of these drugs in the NFL.

Johnson’s story didn’t end with opioid addiction, but it easily could have. Unlike Johnson, many other professional athletes suffered the consequences of addiction because of the easy availability of the substances.

Long before Johnson ever rose to stardom, a dominant running back for the University of Texas was dominating college defenses. Earl Campbell won the Heisman Trophy in 1977 and became the first overall pick a year later.

Due to his power running style, Campbell sustained his fair share of injuries and managed to play through them. However, playing through these injuries would come back to haunt him later in life. In 2009 he was diagnosed with spinal stenosis, which is a narrowing of the spinal canal. Consequently, he was prescribed Oxycontin and Vicodin to ease his pain.

Campbell soon began to mix his prescriptions with alcohol on a regular basis, which had severe implications for his personal life.

In an article written in The Postgame, Campbell stated: “the euphoric feeling of mixing alcohol and the prescribed medication led me to down more pills and drink more beer.”

It wasn’t until his two sons sat him down and told him that he had a problem that he came back to reality. What became apparent to Campbell, as has happened to many others affected by such substances, is that his sense of whether his use was a problem had become impaired.

He has since become sober and has made increasing efforts to demonstrate to others the dangers of addictive painkillers.

The opioid epidemic spreads across professional sports like football and baseball, but professional hockey player Derek Boogaard also fell victim to the opioid crisis.

Boogaard was a professional hockey player for the NHL and during his career played for the Minnesota Wild and the New York Rangers.

His story began when he was prescribed opioids for chronic traumatic encephalopathy, better known as C.T.E, which is thought to be a result of chronic head trauma. Common symptoms of C.T.E. include memory loss, aggression, and addictive behavior.

He had a history of aggressive behavior during his hockey games and was known for beating up his opponents during games.

According to the New York Times, most N.H.L. teams carry roughly 10 affiliated doctors. Although this may seem positive because there were so many resources for athletes to receive medical help, there was a flaw in the system that Boogaard figured out. There was no system in place to track the prescriptions of each doctor. The doctors were oblivious to what their colleagues were prescribing.

This made the perfect environment for drug abuse to flourish. According to records gathered by Len Boogaard provided to the New York Times, in a three-month time period while Boogaard was with the Wild, he received 11 prescriptions for painkillers from eight doctors. In total, Boogaard had prescriptions for 370 painkiller tablets.

It did not end there. In 2010, the Rangers were notified of Boogaard’s history with narcotic pain pills. Yet when Boogaard had an injury, a dentist from the Rangers prescribed him five prescriptions for hydrocodone.

Boogaard’s employers repeatedly failed him by not acknowledging the intensity of his illness and instead further advancing it.

At the young age of 28, Boogaard died from a drug overdose in combination with alcohol.

Time and time again, professional sports teams have sacrificed the long term health of their players in order to help them play through injuries.

Dr. Anna Lembke is an addiction specialist at Stanford, who has reached public prominence for speaking out about the opioid epidemic and doctors’ willingness to prescribe addictive drugs for pain relief. She is the Chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic and Program Director of Stanford Addiction Medicine Fellowship.

According to Lembke, opioids and addiction were not always such hot-topic issues:

“I initially didn’t want to treat people with addiction… [Addiction] was considered a moral problem or a willpower problem,” Lembke said.

However, with time, the perception of addiction by the public began to change. Addiction began to be perceived as a disease, and doctors needed to adjust accordingly. Lembke has helped lead the charge to inform doctors about addictions and the risk of being lenient in prescribing highly addictive substances. With her help, many young physicians are now becoming interested in the complexion of addiction.

“People coming to medical school now are very, very eager to learn about addiction,” Lembke said.

While informing more people about addiction is important, it doesn’t directly solve the problem of opioid usage in sports. To understand this, one must comprehend why athletes use such substances in the first place. While it may seem apparent to many that opioids have negative long term effects, the short term effects can make it worth it to some athletes. The ability to play through injuries and relieve pain temporarily is a temptation that many players can’t resist, regardless of the implications later in life. However, there is a reason that the decision isn’t up to the players.

“The problem is that in the long term, they stop working, so they no longer relieve pain,” Lembke said. “People get in that sort of vicious vortex of kind of chasing that feeling which you can only get if you continue to take more and more.”

There is a lot of stigma surrounding addiction because many people do not understand the science behind addiction. There are many different factors that contribute to addiction that many people do not take into account. Even with outside factors, people with certain genes get addicted while others with those same genes do not, so there is no specific recipe for addiction.

“Approximately 50 to 60% of the risk of addiction is thought to be genetic,” Lembke said. “If you play on a sports team, where athletes who are injured are offered a prescription of opioids, they’re more likely to get addicted as well.”

Athletic injuries are an introduction for many athletes to the world of opioids. Although the initial effects of opioids can be beneficial, the long term effects can be disastrous. The power of opioids is so significant that what once can be seen as a pain remedy, spirals into years of suffering from addiction.

“Their initial exposure is through a doctor, […] and they start out taking it for pain relief for the injury, and then they get caught up in that cycle where they become dependent on it in order to play,” Lembke said.

Some of the appeal of opioid use for athletes comes from the pressure that they are under to be excellent in their desired sport. When athletes have an injury, the expectation is to get back in the game. There is no room for injuries because another player could quickly take your spot in the field. This competitive nature is a perfect storm for athletes to abuse opioids which can lead to addiction. Opioids provide athletes a quick solution for their pain.

“So you can imagine if you had a sports injury and you had to go out there and play, the opioid might just be the perfect drug. It would take your pain away, it would give you energy, and it would make you alert,” Lembke said.

Opioids are extremely dangerous because of their addictive nature, so the use of opioids should be intensely regulated. Team doctors may be a contributor to this issue, but it is ultimately the responsibility of the sports organization.

Regardless of how much team doctors want to limit the prescriptions of players, it can be difficult with the pressure placed on them by their respective organizations. For many teams, if their doctor doesn’t comply, nothing is stopping them from finding a new doctor who will. This organizational power, which is unchecked by the NFL, needs to be regulated to ensure the safety of its athletes.

The appeal of opioids to athletes is evident, so it is essential for sports organizations to regulate how doctors and trainers prescribe them. A failure to do so will result in more players like Tyler Skaggs, who will face health risks that may risk their lives. And every time something happens, we’ll be left to wonder why regulations aren’t in place.

This Genially don't exists