“HE’S-A-WHITE-GUY! HE’S-A-WHITE-GUY!” a large block of seniors vehemently chanted after Holger Thorup (‘12) dunked during the gym rally on the fourth day of Spirit Week.

The chant was directed at the junior class and its two African-American dunkers, E.J. Floreal (‘13) and Aubrey Dawkins (‘13). After both Floreal and Dawkins failed to complete their dunks, it was Thorup’s turn. He connected on a 360° jam, and the senior class erupted. The jubilation rose into an overpowering chant that resonated throughout the gym.

“Can you imagine how the crowd would have reacted if there was an Asian student that could slam it?” Palo Alto High School Principal Phil Winston asked when interviewed about his reaction towards the cheer that he “couldn’t understand,” due to the “muffled” sound quality on the court.

The school’s response to the person dunking, as opposed to the dunk itself, speaks volumes about hidden racial biases that exist in modern athletics.

Sports mirror aspects of society. And just as discrimination, prejudice, and racism live in society, they live in sports. They even exist at places that like to think of themselves as highly evolved and sophisticated, such as Paly.

The ethnic composition of Paly’s 1,916 students is 58.3 % Caucasian, 27.7% Asian, 8.1% Latino, 4.6% African-American, and 1.3% other. The stories of many Paly athletes reveal the existing consequences of this diversity, as racial stereotyping has yet to become totally extinct both on the streets and on the field. Even a seemingly light-hearted cheer offers a glimpse into some of these ingrained stereotypes

As the seniors shouted, their words flooded the gym, drowning out all other noises and echoing in the ears of many, including one Middle Eastern athlete, Sarah, whose name has been changed upon request.

Her passion for her sport grew from a natural love of the game, but playing was not always enjoyable for Sarah. As a Middle Eastern athlete participating on predominately Caucasian teams, Sarah stood out.

Her skin color made her a target for opposing players, who, from time to time, teased her with racial slurs. Because of this, Sarah’s emotions soon began to affect her play on the field.

“We thought I had asthma for the longest time because I would literally start to hyperventilate [while playing],” Sarah said. “I would get so angry and hurt, and I would be half way between crying and not wanting to cry.”

Despite her struggles, Sarah continued to play. After a history of conflict on the field, she learned to ignore her opponents’ crude comments and keep them from impacting her play.

“As you move on and have all [these] experiences, it changes who you are,” Sarah said. “As an athlete, that’s just part of it. People can say things to you and try and bring you down, but you just have to move on. I’ve gotten to the mentality where I feel sorry for [those who stereotype me].”

However, racial stereotyping remained a substantial part of her athletic endeavors. Sarah recalls one game in which she and an opponent repeatedly exchanged seemingly harmless jibes. At one point, her opponent’s frustration reached a peak, and with this came a slew of derogatory remarks, including statements like, “You dumb Pakistani, why don’t you go blow up a plane?”

In another instance, a different opponent addressed Sarah, “You stupid [Middle Easterner]. Shouldn’t you be doing your math homework?”

These, along with many others, were the insults Sarah fended off throughout her sporting career. Learning to build defenses was doable as she soon realized that athletics allowed her to shed cultural labels.

“For me, my sport was a way to get away from both of [my stereotyped] identities and have a separate identity as an athlete,” Sarah said. “[Sports] should be the place where you leave [behind] things like your culture and traditions and your language, the kind of barriers that hold you back.”

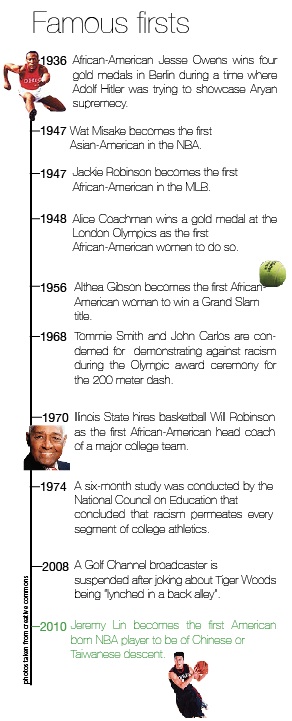

Other Paly athletes have faced similar adversity, including Paly alumnus and current Golden State Warriors point guard Jeremy Lin (‘06).

As a senior, the Chinese-American led the Vikings varsity basketball team to the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) Division II state title, where Paly upset nationally-ranked Mater Dei. Although Lin was regarded as “the runaway choice for player of the year by virtually every California publication,” according to a Dec. 2009 article written by ESPN’s Dana O’Neil, he “didn’t receive a single Division I scholarship offer.”

While Lin acknowledges that being undeveloped physically may have played a role in his under-recruitment, he also believes that his ethnicity was part of it. Nevertheless, Lin’s stellar play on the court and superb performance in the classroom allowed him to walk-on to Harvard University’s basketball team in 2006 and continue to prove his doubters wrong.

During his college career, fewer than 0.5% of all NCAA Division I college basketball players were of Asian-American descent. Nevertheless, these low numbers did not discourage Lin.

Lin was selected to the All-Ivy First Team his senior season after averaging 16.4 points, 4.4 rebounds, and 4.5 assists per game. Despite these impressive collegiate numbers, Lin went undrafted in the 2010 NBA draft. Lin, however, did not give up. He found his way onto the Dallas Mavericks’ Summer League team, where he impressed NBA scouts. From there, Lin received offers from several NBA teams. On July 21, 2010, Lin signed with the Warriors to become the first American-born NBA player to be of Chinese or Taiwanese descent.

Breaking this new ground was a moment of pride for Lin, who reflected on his stereotype-shattering passage.

“I know that my journey has taken me on a path that has overcome many stereotypes, and I am just thankful for that opportunity,” Lin wrote in an email. “I really hope to break more stereotypes as my career progresses.”

Lin professes a positive attitude towards both his past in basketball and his future, but like Sarah, this attitude grew from despairing moments.

“At first [the ethnic profiling] was really discouraging, but I’ve learned to make it a positive thing, and it has given me an extra chip on my shoulder,” Lin wrote.

Like Lin, Asian-American varsity basketball player Aldis Petriceks (‘13) has been subject to discrimination.

“I get made fun of a lot for my race,” Petriceks said. “For instance, sometimes people just call me ‘chink’ randomly on the court, even when I do something good. If I catch a bad pass, people might say, ‘I’m surprised you even saw that ball, small eyes,’ or if I make a shot, sometimes they say, ‘You deserve a rice bowl for that.’ And you know, I’m just sick and tired of that.”

Although disheartening, these discriminatory remarks strengthened Petriceks, who can relate to Lin because of their cultural and athletic similarities.

“All of the racism that has been displayed in front of me has forced me to toughen my skin and improve my mental toughness to withstand the insults on the court, just like [Lin does],” Petriceks said. “What [Lin’s] done has really inspired me to follow in his footsteps.”

While others lowered their expectations of Petriceks and Lin because of their ethnicities, for Petriceks’ teammate and junior Spirit Week dunker Floreal, his ethnicity has had the opposite effect.

“Just because you’re black, you’re supposed to be good at sports,” Floreal said. “It puts a lot of pressure on you.”

The higher standards Floreal feels his teammates and opponents hold him to often undermine his accomplishments.

“If I do something special or great in my mind, people still say, ‘Oh, you’re black. You are supposed to do that,’” Floreal said. “If I was a white guy or an Asian guy and I did some of the stuff that I do, I’d probably get a lot more credit.”

Although Floreal’s ethnicity altered his peers’ perceptions of him, for fellow African-American Paly athlete, Lauren, whose name was changed for the purposes of this article, her ethnicity has made her feel out of place. She compares the different cultures in both soccer and basketball, recalling her experiences on various soccer teams in her youth.

“There were a few other mixed girls [on the team], but I was the only full black person, so I really stood out,” Lauren said. “I had to get used to being not only the only black person on my team, but the only black person in a tournament.”

Stereotypes work in multiple ways. Minorities, like Lauren, may be more frequently stereotyped, but majorities are nevertheless stereotyped as well. For Caucasian badminton player Alex Carter (‘12), playing in a sport perceived to be dominated by Asians made him feel alienated by opponents prior to his matches.

“People assume I’m bad [at badminton] just because I’m white,” Carter said.

With this feeling of inferiority, created merely because of a difference in ethnicity, not only is Carter’s confidence lowered, but he also feels “a lot of performance pressure.”

Latino football and lacrosse player Gabe Landa (‘12) can relate to Carter, as he is also used to being a minority in his particular sport.

“I actually don’t know any other Latino lacrosse players,” Landa said. “None of my family [knew] what lacrosse [was], and they only [now] know because of me.”

While Paly’s athletes have experienced forms of racial bias on the field, discrimination also occurs on the sidelines on the part of coaches.

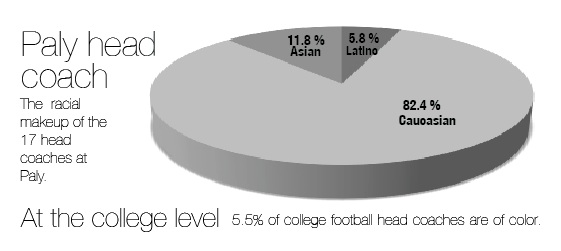

Asian-American football, track-and-field coach and Paly alumnus Jason Fung is one of three non-Caucasian head coaches at Paly. Fung recalls a specific instance of racial bias by coaches, at the track-and-field Central Coast Section (CCS) finals a few years past.

“[There was a] black coach and a white kid long jumping,” Fung said. “The white kid messes up, coach turns around, and whispers, ‘Damn, I wish I had black athletes!’”

Paly football head coach and Athletic Director Earl Hansen does not tolerate such behavior by coaches on his staff.

Hansen, who is Caucasian, said, “[If a coach were to discriminate] it would get [him or her] fired, and I would be very supportive [of the decision to fire the coach]. Basically the coaches that I hire are trying to, every time, play the best players. It doesn’t have to do with anything else.”

Fung agrees with this policy, and he expresses the same beliefs in his own approach to coaching.

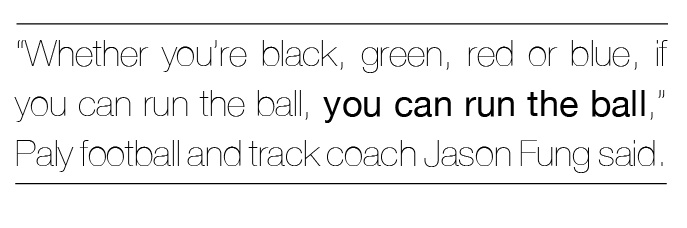

“For us coaches at Paly, there’s really no profiling,” Fung said. “Whether you’re black, green, red or blue, if you can run the ball, you can run the ball.”

While coaches generally refrain from player discrimination, spectators sometimes do not. After a junior varsity football game against Los Gatos in the 2010 season, a Los Gatos fan directed a discriminatory slur at African-American varsity football player Tyrus Whitehead (‘13) and his teammates.

“Right after the game when we had lost by a touchdown, some [one] in the crowd [said], ‘We hang n****rs like you on this side of town,’” Whitehead said.

“Right after the game when we had lost by a touchdown, some [one] in the crowd [said], ‘We hang n****rs like you on this side of town,’” Whitehead said.

Even though this extreme instance may be unusual, members of the Palo Alto Unified School District (PAUSD) administration, including Winston, have yet to see any examples for themselves.

“It might be naïve of me to say [discrimination] doesn’t exist,” Winston said. “[However] I have not personally seen it. That would be just like me saying students don’t drink. I’m sure it happens. I just don’t see it.”

Lauren, on the other hand, has experienced stereotyping firsthand, and firmly believes it exists on campus, regardless of what others might say. She believes that Paly’s administration may have a limited perspective on the issue, and addresses what she believes to be their general perception of the matter.

“‘I don’t see racism because I’m a 40-year-old white guy, so I wouldn’t know,’” Lauren said, mocking the view of the administration.

PAUSD superintendent Kevin Skelly shares a similar viewpoint to that of Winston.

Skelly, who is Caucasian, said, “I don’t see [discrimination] directly, but I think [it comes] up.”

Although Winston and Skelly see no tangible examples of discrimination, the district is still working to dissolve racial stereotyping. According to the “Nondiscrimination and Section 504 Grievance Policy” listed in Paly’s 2011-2012 Handbook, “The Board of Education of the Palo Alto Unified School District shall provide equal opportunities in all areas and assure that there will be no discrimination against any person on the grounds of race… and color.”

To spread awareness of the cultural differences in the PAUSD community, the administration has also recently developed a workshop called ‘Teaching and Leading with a Cultural Eye.’

“It’s a [three day workshop] in which we have speakers who talk about what your expectations are in class, how are you taking on these kinds of issues, [and] the kind of things you do in the classroom to create a culturally sensitive environment,” Skelly said.

Another way PAUSD combats discrimination is through Camp Everytown, a four-day student-teacher retreat to Boulder Creek, California.

African-American Living Skills teacher and Camp Everytown staff member Letitia Burton describes the purpose of the outing.

“With Camp Everytown, we really try to look at all those stereotypes, whether [they are] conscious or unconscious,” Burton said. “We know that all these racial stereotypes exist and we all grow up with them. [We try] to make that all conscious and bring it to the forefront, and to really see how these stereotypes hurt people on very personal levels.”

Concerning sports, Burton acknowledges the possibilities of discrimination in sports, but also the opportunity to unite.

“I think any time you are on a team when you bring people of different backgrounds together for the benefit of the team, [people] can [come] together,” Burton said.

Lauren agrees, and traces many of her current friendships back to the sports teams she has played on.

“I feel like if I had not been playing sports, I most likely would not be talking to a lot of [the people I talk to now],” Lauren said. “It makes life so much easier to have as many good, trusting friends as possible, and especially to have diversity among your friends. I would never have gotten to that amount [of friends] without sports and the diversity it brought.”

Skelly also believes that sports do more to unify than to divide.

“Sports [do] much more to unite. Athletics in general [require teammates to] cheer, support and count on people of all kinds,” Skelly, a former basketball and tennis player said. “You’ve got to understand their tendencies and where they’re weak. If you’re playing with someone who can’t shoot, you’ve got to find ways for them to be an asset to your team. As a teammate, put them in a position where they can be helpful. I think sports are a great way to get a window into somebody else.”

The barrier-breaking potential that makes the sports environment unique stems from the very nature of team competition. Every sport from swimming to football is based on performance, and with this, carries an equal playing field for all athletes.

“There are certain cliques within our team based on race,” Asian-American varsity basketball player Alec Wong (‘12) said. “But once we’re on the court, it doesn’t matter who it is. We still pass the ball to whoever is open, whether they’re black, white or Asian.”

Regardless of the attempt to avoid the use of racial stereotypes, Skelly believes the tendency of athletes to occasionally profile still exists.

“Often we want to draw conclusions about someone without trying to understand them,” Skelly said. “Your conclusion is not necessarily what you are trying to learn or how you’re trying to understand that person.”

As Skelly states, people make assumptions.

They range from ‘He’s white, so he can’t jump,’ to, ‘He’s black, so he’s supposed to be good at sports.’

But each athlete is different. Each one comes from unique backgrounds and experiences. Each has a different shape, size and color. And focusing on the exterior takes away from an athlete’s accomplishments on the field. Unity and teamwork are colorblind, or as they teach at Camp Everytown, “color-conscious.”

On the surface, a player like Thorup might be a “white guy,” but beneath the surface, he is just another athlete striving to be the best he can be. Sure, he can hear the booming chant of his fellow seniors, but that is not where his focus lies. In the athletic arena, players forget their ethnic, religious, cultural, and all other differences to unite and strive for one thing: victory.