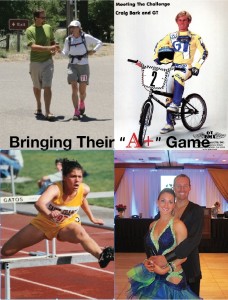

Sitting in a small wooden desk in a Paly classroom listening to a teacher, one would normally focus on the words coming out of the teacher’s mouth. A student might focus so much energy on doing well in a class that they take little time to think about who their teachers really are, and who they were. Looking up at a teacher, a student may find it hard to picture their teacher as a teenager, harder yet to imagine that teacher as an accomplished athlete. However, Paly is full of teachers who one did and still do participate in competitions. From a BMX racer to a ballroom dancer, it seems that Paly teachers have done it all. But one important question remains: “Who are Paly’s teacher-athletes?”

Craig Bark

At a young age, Paly English teacher Craig Bark participated in a sport that not many kids play. Bark was involved in bicycle motocross (BMX), or racing 20 inch BMX bikes around a dirt track.

“I started when I was 11 years old,” Bark said. “I had ridden on bikes my entire life and I had a friend who started racing. I went with him, realized I was good and kept going.”

A big part of racing back in 1983 was getting sponsorships from various bike shops or franchises to support travel to global events and to build up a name for oneself.

“I started racing with no sponsors, then a bike shop wanted to give me parts and discounts if I wore their jerseys,” Bark said. “I was eventually sponsored by big factory teams, such as GT and Torker, once I got really good.”

Bark competed in almost every state in the country, as well as in Holland, Germany and Australia. Bark credits his parents’ support as a key to his success in BMX.

“My dad would work extra jobs just to get me money so I could travel,” Bark said. “The company did pay for a lot but I did need spending money for food and things of that sort. They did it as long as I kept a B average.”

Bark was able to excel and stand out in the amateur racing world mainly because of one important race in Morgan Hill.

“There is this one weekend in my life where I became famous,” Bark said. “I was racing for Robinson [an original BMX company]. I was doing well. Then I started doing really well. I started winning national events, which is where people from all over the country come and race.”

Bark’s improvement in his racing sparked the attention of GT, who approached his father, informing him that if Bark performed well in Morgan Hill, he could have a spot on the team. Bark did just that, which took his career to the next level.The more successful Bark became, the more opportunities he had to travel for competitions.

“When I was on GT we had to go to bike shops. We had to make appearances over the summer tour. We had to be in a certain city on a certain day. I had a schedule…I had to sign autographs, practice, race, and go back to the hotel.”

In 1983, Bark traveled to Australia at the age of 13 and became the world champion for his age group. Two years after this, Bark decided to quit motocrossing.

“I stopped because I didn’t love what I did and I didn’t want to ride my bike every day,” Bark said. “After becoming an English major I realized I wanted to be an English teacher and I wanted to work for the best school possible. That is why I came to Paly.”

Bark credits motocrossing with teaching him many valuable life skills, including how to handle finances and negotiate with companies.

“It made me confident,” Bark said. “It taught me that I am responsible for myself and how people see me and if I wanted to do something I could do it. All I needed was to work hard and be honest with myself.”

Even though Bark does not race anymore, he still keeps up with the sport.

“I go to the BMX hall of fame every year,” Bark said. “I’m not in it but most of my friends are, I didn’t race long enough.”

His experience in racing also helps him connect with his students. Bark is understanding of the commitments that students make for athletics.

“The amazing athletes here remind me of my high school experience…. their sports are important to them,” Bark said. “As a teacher I really respect those athletes and try to give them leeway to enjoy their sports, and push them academically as well.”

Michelle Steingart

Biology and chemistry teacher at Paly, Michelle Steingart was a college runner for Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Steingart began her running career at Saint Francis High School.

“I first started track in high school,” Steingart said. “I ran hurdles and short sprints up to 400 meters starting my sophomore year.”

Steingart was a competitive athlete in California, placing fifth in the state her junior year of high school. Her senior year, she made it to the state championship; however, she did not perform as well due to an injury she sustained earlier that season.

“The shoulder dislocation—I still remember the date—it was my senior year, April 17,” Steingart said. “I wish I could take that day back because my shoulder has never been the same.”

She had to rest the shoulder, missing a critical meet against Los Altos during that season. Stephanie Downey, one of Steingart’s main competitors from Los Altos, was upset when she found out Steingart would not be running in the meet.

“She’s my nemesis, so I was a little bummed,” Downey said in a beat, Downey and Los Altos down St. Francis by Andy Nystrom.

As it turned out, Downey had many more opportunities to run alongside Steingart at Brown University.

Steingart, recognized for her academic achievements, received a $2,000 college scholarship award that only went out to 10 student-athletes in the state that year. Additional praise came from her high school coach, Roberta Chisam.

“Michelle is the type of athlete you wish everybody was,” Chisam said in the article. “She’s dedicated, a leader and cares about her teammates on and off the field.”

Although Steingart entered college healthy, she struggled with injuries over her next few years.

“I had shin splints and stress fractures my freshman year,” Steingart said. “Then I had mono. I took some time off and I came back, but it was never the same.”

Despite being injured, Steingart did what she could to stay in shape.

“I found different ways of exercising,” Steingart said. “It was about running in the pool or doing laps, or doing intervals on a bike.”

As she transitioned out of college, the length of her workouts transformed.

“After college it is hard to sprint for fun,” Steingart said. “I started running longer distances and I tried to run about three to four times a week.”

Steingart continues to run long distances now, but her job and her kids don’t allow her to run as often as she would like.

“Before kids I did some half marathons and some 10K’s, but since having kids I don’t really have time to start training longer,” Steingart said. “When I have more time again I do want to compete in a half marathon again. I have some goals there as far as times and pushing myself to get better.”

The reason she runs and the reason she hopes to run more in the future is because of the feeling running brings her.

“I enjoy exercise because it makes my body feel really good,” Steingart said. “I like sweating and I like that feeling you get after working out.”

Shirley Tokheim

When most Paly athletes want to get in shape, they run for a couple miles – nothing too long, just enough to get in a good workout. They head out, meander their way around their neighborhood for a bit and then return home.

Taking an entirely different approach towards running, Shirley Tokheim, an English teacher at Paly, chose to compete as an ultramarathon runner. Ultramarathons are races that are longer than marathons. She first began running in graduate school nine years ago.

“I met someone who ran 100 milers and suddenly it felt like a fun thing to aspire to,” Tokheim said. “I was running twenty minutes a day, a couple miles a day. He said slow down and you can go a lot farther.”

Competing in a 30K at first, she then went on to run a marathon. Increasing the distance in her races, she then ran a 50K, followed by a few 50 milers, and a 100K. She also attempted a 100 mile race; however, painful blisters caused her to stop 30 miles short of the end.

Blisters were not the only problems Tokheim faced when running.

“When I ran the 100K it was really hot,” Tokheim said. “It was 90 degrees and it was up and down hills. I had trained really well, but sometimes your stomach doesn’t always work. You have to manage your body, make sure you don’t get dehydrated. You have to make sure you take enough salt in and make sure you eat enough.”

To prevent problems from occurring, lots of preparation was put in for each race.

“When I was training for the 50 milers I would do back to back runs, so I would run 22 miles one day and the next day when I was still tired, 20 miles,” Tokheim said.

For the 100K and 100 mile run, the entire day was spent running.

“The races are super long,” Tokheim said. “You get up and start at five or six in the morning, you eat along the way, you talk to people and it is this whole deal. It is not this fast race where you are running really fast and you get tired. It is an endurance race.”

Instead of worrying about her times and her placement compared to other runners, Tokheim mainly focused on crossing the finish line.

“It’s all about pacing yourself and going aid station to aid station, which are typically seven to 10 miles apart,” Tokheim said. “You break it up into little chunks in order to finish the long thing. It’s like writing a paper. You break it up into little parts and then its something that you can do. As opposed to sitting down and writing a paper.”

Even though Tokheim does not have enough time now to train for races with work, she still manages to run once a week.

“I don’t run as much now,” Tokheim said. “My runs are much shorter, but I always run on trails, so it’s always beautiful. It’s nice to feel like you can set a goal, work towards it, and then accomplish it.”

Tokheim sees herself running races in the future, but is unsure of the distance she wants to compete in.

“I would like to say that it is on my list to finish a 100 mile, but the reality is that the amount of time it takes to train, I wouldn’t be able to work,” Tokheim said. “I would need lots of time to train. Maybe the next race I’ll run will be 50K and that will be long enough.”

Tokheim benefited from running and all the training she put herself through.

“It showed me that if I stuck with something long enough, I could accomplish something big,” Tokheim said.

Melissa Laptalo

Many people can remember being placed into dance classes as small children. They often decide to move onto other sports and activities, but Melissa Laptalo, Palo Alto High School English teacher, stuck with it since she was a little girl and now competes regularly as a ballroom dancer.

“I started when I was three years old,” Laptalo said. “I grew up doing jazz dancing. My first lesson in ballroom dancing was when I was in college. I took this class where the instructor was a competitive ballroom dancer, and asked me to be his partner, and I got swept up really quickly into this world and I’ve been doing it ever since.”

Laptalo and her husband compete locally in the Bay Area four to five times a year. A competition usually spans an entire weekend, where eight or nine pairs dance every round and are ranked. To prepare, Laptalo and her husband practice four different routines three days a week.

“Minor changes can make a major difference,” Laptalo said. “At practice, we do a lot of work on what things are supposed to look like, we drill it a bunch of times because the way you look in dance matters a lot.”

In dancing, both partners must perform well in order to succeed. For Laptalo, dancing with her husband has its pros and cons.

“You have a lifelong partner,” Laptalo said. “Dance partnerships break up often because people have different schedules, different levels of commitment and different things going on in their life. Also, there’s no jealousy. If you’re dancing with someone else that plays a factor. It can be a little upsetting watching your spouse touch somebody else.”

Laptalo acknowledges the challenges to dancing with a spouse.

“Sometimes you get too comfortable,” Laptalo said. “We get distracted a little too easily. If you have a problem at home, it’s hard not to bring it up on the dance floor.”

Laptalo emphasizes that she and her husband complement each other by bringing different strengths to the dance floor.

“I can pick up choreography faster,” Laptalo said. “I’m more into the showmanship, things on the surface level. My husband is very good at the technical side of dancing; he has more knowledge. He helps me with the smaller details.”

Together, they balance time between their jobs, practice, and competitions.

“The main challenge is time,” Laptalo said. “We practice one to two hours and there are only so many hours at the end of the day. Often times, a struggle is having all my grading done and having my dance lessons.”

In terms of her dance future, Laptalo is open-minded.

“When we choose to start a family, we won’t dance competitively,” Laptalo said. “We might just do show dances, where you’re not competing against anyone.”

Regardless of Laptalo’s future with dance, it will always be a big part of her life.

“Dance is kind of like therapy,” Laptalo said. “It’s expression; it’s pushing myself in a way that I’m not sure I can achieve. it helps me understand who I am. I picture us as old people dancing together, it’s always going to be a part of my life, whether it’s competing or just dancing around the house.” <<<