BURNOUT: When more isn’t better

December 19, 2022

It all started one sunny fall afternoon when a young girl was running up and down Peers park playing with friends. She ran until her nose turned pink in the cold air, her hair flying around her head as she hurriedly kicked the ball forward. Suddenly a defender appears by her side and she quickly maneuvers around the defender and then, “SCORE!” She scored her first goal and from there she fell in love with soccer. Her parents signed her up for the local club team AYSO, the following week. Starting at four years old, senior Finley Craig started her athletic journey.

With any sport comes the draining three-hour practices full of endless drills and mind-numbing laps, countless amounts of tournaments, Craig felt her love for the sport beginning to end. However, during freshman year, Craig was presented with a new sport to try: Cross Country. She found liberation in the freedom and new-ness of running, and it being “just for fun”. What wasn’t enjoyable, though, was trying to balance the time between being a multisport athlete and a full time student. After sacrificing many family vacations and hang-outs with friends the two-year struggle between soccer and her cross country came to an end. Craig eventually made the tough decision to quit the sport she had grown up playing.

Juggling the training for both sports  was emotionally and physically draining, but the real devastation was the realization that she had to let go of something that had been a part of her identity for the entirety of her childhood. Craig came to realize that the time and energy she put into her soccer career was a huge part of her life, and with it gone, she would have to rediscover who she really was.

was emotionally and physically draining, but the real devastation was the realization that she had to let go of something that had been a part of her identity for the entirety of her childhood. Craig came to realize that the time and energy she put into her soccer career was a huge part of her life, and with it gone, she would have to rediscover who she really was.

Most athletes begin their sport at a young age, encouraged by their parents or joining friends in a new activity. The sport grows with them as they age from kids into teenagers, then to young adults, becoming every part of their life and who they are.

Often, athletes feel pressured to stay in a sport even when they no longer find enjoyment, face injuries, or find themselves in a toxic environment. Burnout is much more common than many think, but when an individual makes the hard decision to quit their sport, what happens to their identity? How do they discover themselves as a different person independent of athletics?

To begin, athletic burnout must be defined.

Burnout forms slowly over time and is made up of several different components. Generally speaking, athletic burnout is a response to the stress of the continued demands of a sport without the opportunity for physical and mental recovery.

Although this definition covers the basics, the explanation of burnout that is more true to life is a little different. The factors of burnout tend to relate back to one idea: identity. The pressure to perform well to uphold the self-image of “an athlete,” the over-emphasis on one sport to be “that athlete,” and the devastation of injuries because they stop people from being

“the athlete” they want to be. Burnout is about identity.

Sports have an incredibly large impact on high schoolers. Our culture revolves around them, in implicit and explicit ways: from attending games, playing in them, talking about them, to wearing clothes from sports teams. Many younger athletes dream of going on to collegiate athletics, or even of competing at the professional level. They feel that letting go of a sport will drastically affect their future for the worse by limiting options for college, jobs, or even fundamentally shifting who they are aside from giving up on something that had been a part of them for so long.

Paly students already struggle with external expectations with respect to academics, from family, friends, teachers, and society. Ideally, athletics are a place to relax, have fun, and be yourself. However, the external pressure to perform well from coaches, teammates and parents, as well as the internal pressure to perform well, often creates more stress than fun––leaving athletes with little motivation to continue to play and compete at a sport.

Senior Brooke Threlkheld, a former competitive club swimmer, now runs cross-country in the fall and swims for the more-relaxed school swim team in the spring. Threlkheld started swimming when she was less than a year old, and had been competing since the age of seven. Her love for the sport began to falter when the external pressures of club swimming––the emphasis on winning medals and placing first––made the practices less enjoyable.

“When I started swimming, it was a really chill team, focused on friendship and just trying your best,” Threlkheld said. “[But] then the team shifted into being focused on times and being the best. I still swim for Paly [because] it goes back to the root of being a team, and I felt like club swimming is more individually focused.”

Coaches and parents have a big role when it comes to easing the external pressure to perform at a high level. Encouraging athletes to take breaks to recover mentally and physically when needed is an important part of the sport.

Paly varsity boys basketball coach and former collegiate coach, Jeff LaMere, speaks on the importance of taking care of his athletes.

“When I coach, the biggest thing for me is the health and mental welfare of student athletes,” LaMere said. “They need to be in a great headspace to be ready to improve. I as a coach need to understand all the pressures that are on them. Especially at Paly, we have student athletes trying to be the best at everything they do.”

According to a study by UC Health, rest and recovery are “critical for an athlete’s physiological and psychological well-being.” When athletes step away it allows them to fully recover and help prevent burnout.

“We need to be able to manage their work loads –– many student athletes only play one sport and are playing that sport year round,” LaMere said. “One of the biggest pieces of anything is having rest, there is this idea that the more you work the more you get better, there are so many more benefits to having a good balance of rest and work.”

In addition to the external pressure from coaches or parents to do well, there is internal pressure from the athlete themselves. Some are so focused on being the perfect star athlete––perfect stats, perfect performance, perfect times–– that the aspect of individual and team growth is lost. Constantly striving for this perfection will not only lead to dissatisfaction but also often in turn will negatively harm mental and physical health, causing burnout.

Junior Mary Henderson, a competitive swimmer and water polo player, began swimming at age eight and playing water polo at age twelve. Henderson has firsthand experienced the effects of burnout and has thought about quitting both sports because of her internal expectations of her performance.

“I definitely do get burnt out playing my sports simply because of the sheer amount of time I put into both of them,” Henderson said. “It is difficult for me mainly because of how mentally draining it feels after putting in hours of training and practice, just to have a bad game.”

Finding ways to help prevent athlete burnout can be extremely effective. Henderson explains how her burnout was caused by her internal mindset.

“I found that associating your self-worth with athletic performance is a sure method to deteriorate mental health,” Henderson said.

On top of external and internal pressures creating burnout, another big factor is the environment an athlete competes in. A harsh coach, bad team chemistry, disliking your position, differing team and individual expectations, or unhappiness with practice schedule, can shift the amount athletes enjoy what they are doing, making the sport more mentally draining and less fun.

Paly junior Gali Nirpaz used to dive competitively for the Stanford Diving Club. She made the difficult decision to quit the team her sophomore year because of an array of factors, mostly based on the environment she found herself in when competing at a higher level.

“When sophomore year hit I was put on a higher team with a coach that did not like me,” Nirpaz said. “I was put in a group that I did not like at all. I was away from all of my friends, it was too much. I was completely miserable diving and there was nothing enjoyable [about it].”

As previously mentioned, sports are designed as a place to have fun and relax. It is a way for athletes to block out the stress of school, work, and real life. However, when the athletic environment loses its excitement, it is no longer a mental escape. This leads to added stress and often burnout. LaMere reflects on how coaches perceive this.

“If there is no joy in it, it is hard for anyone to do and certainly you can not have joy when you do something all the time,” LaMere said.

Coaches are not mind-readers. It is hard for them to recognize when a person is being pushed to hard, or no longer enjoys what they are doing, like Nirpaz.

“There was a point where I was completely breaking down every practice,” Nirpaz said. “I stopped pushing myself as much as I was before.”

However, coaches are there to help. Communication between athletes and coaches is key. Talking through taking a break, or shifting practices to make the sport more enjoyable again to the athlete can exponentially improve the mental well-being of an athlete. As LaMere points out, the coaches are there to help the athlete and work through rough times.

“If [playing your sport] is something that makes them unhappy, I would like to talk to them because if it was something to do with me I want to get better, or if something was wrong with the team.” LaMere said.

Unfortunately, communication is not always the solution to burnout. One large factor is very unpredictable and uncontrollable: injuries. Although they are certainly a normal part of physically exerting your body, they also often lead to burnout.

Senior Rachel North played soccer her entire life, competing at the club level for Palo Alto Soccer Club and had full intentions of playing at the collegiate level. After playing on broken bones that were not given proper time to heal for months, North now needed bone removal surgeries on both feet. The two surgeries, done a year apart from one another, left North with persistent pain and inability to continue to play, forcing her to quit playing the sport.

“I wish that this wasn’t the outcome, but [the surgery] was a forced decision,” North said. “I really miss [soccer], though it is something I can be thankful to look back on.”

Spending all or most of one’s younger years playing exclusively one sport can lead to injuries or burnout. When this happens, athletes are often left confused and lost; not knowing what to do next. After years of intense physical activity, It can be hard to find other ways of getting exercise or finding that special group of people that one would find within a team. North, after losing soccer due to injuries, found weight training as a passionate replacement.

“The lack of exercise made the switch [from soccer] really hard for me,” North said. “I was able to start weightlifting to compensate, which is something I do daily and love now!”

Senior Jacob Kasanin similarly was forced to quit soccer due to injuries.

“I broke my toe playing soccer in 8th grade and played the rest of the season and didn’t get it checked,” Kasanin said. “[This] led to me compensating by walking on the outside of my foot, a habit that eventually broke the cuboid bone on the outside of my right foot.”

The most difficult part about injuries is the desire –– but inability –– to play your sport. Many athletes, North and Kasanin included, continue to play while hurt, worsening the inital injuiry. Furthermore, the recovery process can be frustrating and draining through hours of physical therapy while watching teammates and friends continue to play.

“I had to go through a lot of physical therapy, which I did not take seriously, so my gait did not heal and the doctor said that I couldn’t play soccer for the season,” Kasanin said. “This was frustrating but also my fault.”

Athletes tend to be experts at pushing themselves, always going faster, always working harder and wanting more. What is so challenging, however, is the knowledge that the only way to get better is to take time off and let the body heal. Sometimes this means people continue to play regardless of injuries, further and more seriously hurting themselves or becoming overly frustrated by the recovery time and quit playing the sport altogether.

“This injury mainly led to a lot of frustration, because I just kept wanting to go out and play, and each time I tried [to play], it would still hurt,” Kasanin said. “Because my gait had been messed up for so long, I had to relearn how to walk properly, which took a long time.”

In the end, Kasanin quit soccer, after months of on-and-off, and hours of physical therapy. The loss of this salient aspect of his life was, although at first challenging, liberating in some ways. Quitting soccer gave freed up his time, allowing him to explore other hobbies, like tennis and surfing.

With or without an injury the varying factors of burnout add up to an immense amount of stress on an athlete as they begin to question if that is what they really want to continue doing. All of the things that can influence an athlete’s decision to quit their sport or getting burnt out are almost universal experience. Every athlete experiences some of these factors one way or another, it is inevitable that people will need breaks, even though not all athletes leave their sport.

Craig, went through a lot of tough decisions when she decided to quit soccer to continue running. She spent years debating whether or not to quit soccer until all the factors lined up.

Although she felt like her soccer team’s condition was very toxic, Craig’s coach was very supportive through the whole process. After months of choosing not to quit soccer, the final push to quit was when Craig had to receive a double foot surgery to fix an injury. She found that there wasn’t enough time or energy for her to balance participating in both soccer and running.

After many long discussions with her parents and coach, Craig’s decision had no impact on her relationship with the coach and her old teammates.

“I think people need to realize that [they’re] allowed to leave,” Craig said. “People should allow themselves to quit a sport and not worry about being judged for it. I didn’t lose any of my friends that were on the soccer team. And the coach was really kind and caring throughout the process.”

It took some time to get over the emotions from leaving a sport. However, Craig had to soon face the new challenge of discovering her identity outside of soccer.

When an athlete is deeply invested in their sport, it becomes who they are and often a large motivator for the future. What happens when that part of themselves is taken away, or removed?

When Threlkheld decided to quit club swimming after being part of the team since she was a toddler, she felt lost. After all, losing a sport is like losing a part of yourself. She had to find new things that she enjoyed and not just do things because she was good at them.

“With running, it allowed me to like find things that I’m passionate about,” Threlkeld said, “I got to test things out and now I have a better understanding of who I actually am rather than who I thought I was.”

Although Threlkeld had regrets at first but found herself in a new community that was supportive and different from the competitiveness she was wanting to get away from.

Similarly, Craig found a community that she adored and discovered a sport that she was very good at and loved. From being a part of a very competitive and toxic environment she found this change like a breath of fresh air.

“I wasn’t as social because I didn’t really have a lot of good friends on the soccer team, it was basically just the ones who went to the school,” Craig said. “Now after I quit, I’ve branched out with my friends through all the grade levels. And we do so many team bonding things as a team and I enjoy going to practice so I think overall, I’m just a lot happier.”

Feeling initial regret or sadness was a common theme among athletes who ended up quitting their sport. However, they often found themselves in a new light and discovered what they really enjoy doing.

Other athletes pick up completely unrelated sports to their previous one. Kasanin, for example, took a long time to recover from his injury. When he came out on the other side of it, he explored some of his other interests and found hobbies were less painful than playing soccer on an injured foot.

“I decided to pick up tennis and later surf.” Kasanin said, “I now teach surfing every weekend in Half Moon Bay, which has been a great experience and something that I wouldn’t have picked up if I was still playing soccer.”

After finding new things to enjoy, these athletes discover a new sense of self and feel that they become a better version of themselves.

Mental health issues have become a really prominent issue in today’s society. The effects of having good mental health is shown to be very beneficial to the overall quality of life. Schools across the country are beginning to prioritize mental health over anything else by giving students access to wellness needs. However, not many athletes have had the same experience. It is much harder for athletes to cope with sports-related mental health issues, due to the lack of knowledge and research, along with the stigma surrounding the idea.

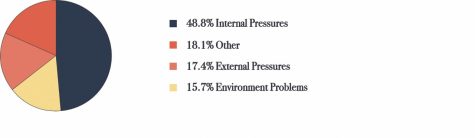

Many athletes across the world are affected by burnout, whether they realize it or not. There are many ways that cause burnout, whether it be internal pressures, external pressures, bad environments, injuries, and much more. The line is drawn once a sport becomes mentally overwhelming, rather than a mental escape. The mental and physical stress that comes with it is something that should be addressed more.

“For any of these students if they are student-athletes or not, go talk to someone, reach out to a coach or a teacher,” LaMere said. “If you stop doing it doesn’t mean that you’ve failed. Sometimes change can be great.”