Coach’s Corner

The women shaping the next generation of athletes

May 23, 2020

Throughout their career, every athlete has had a mentor that has helped them grow in exceptional ways and strive to reach their full potential. Whether it be a coach, parent, or sibling, these influential figures play a significant role in shaping one’s character and work ethic. However, many young girls in sports miss out on the opportunity to engage with strong female leadership and the respective connections that emerge from such relationships due to the disparately low number of women hired to coach local or professional sports.

Over the years, increasingly more women have managed to make a name for themselves as coaches for both men’s and women’s teams around the world. For example, in 2019, San Francisco 49ers football coach Katie Sowers became the first female and first openly gay offensive assistant in the Super Bowl.

In our own Palo Alto community, many women hold coaching positions for all levels and all types of sporting events. With each and every connection made, these coaches highlight the importance of female leadership and diversity in sports.

Brandi Chastain

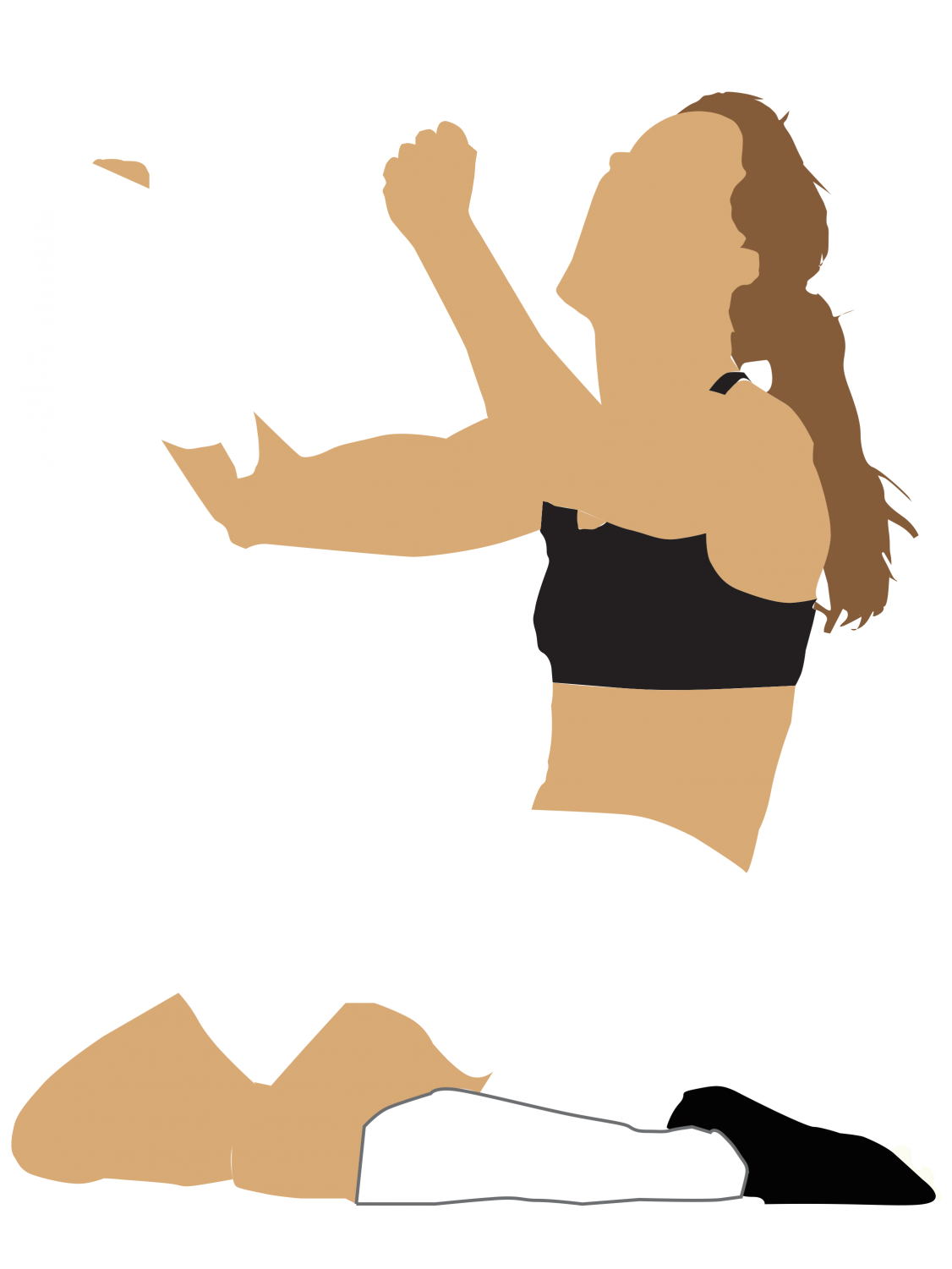

After scoring the winning penalty goal over China for the United States at the 1999 FIFA World Cup Final, soccer player Brandi Chastain celebrated the victory by ripping off her jersey and falling to her knees in a sports bra. This became the subject of what is now considered one of the most iconic photographs of a woman celebrating an athletic victory.

However, that spontaneous moment represented more than an act of female empowerment. It represented Chastain’s love and passion for her sport, which she now hopes to pass on to the next generation of athletes.

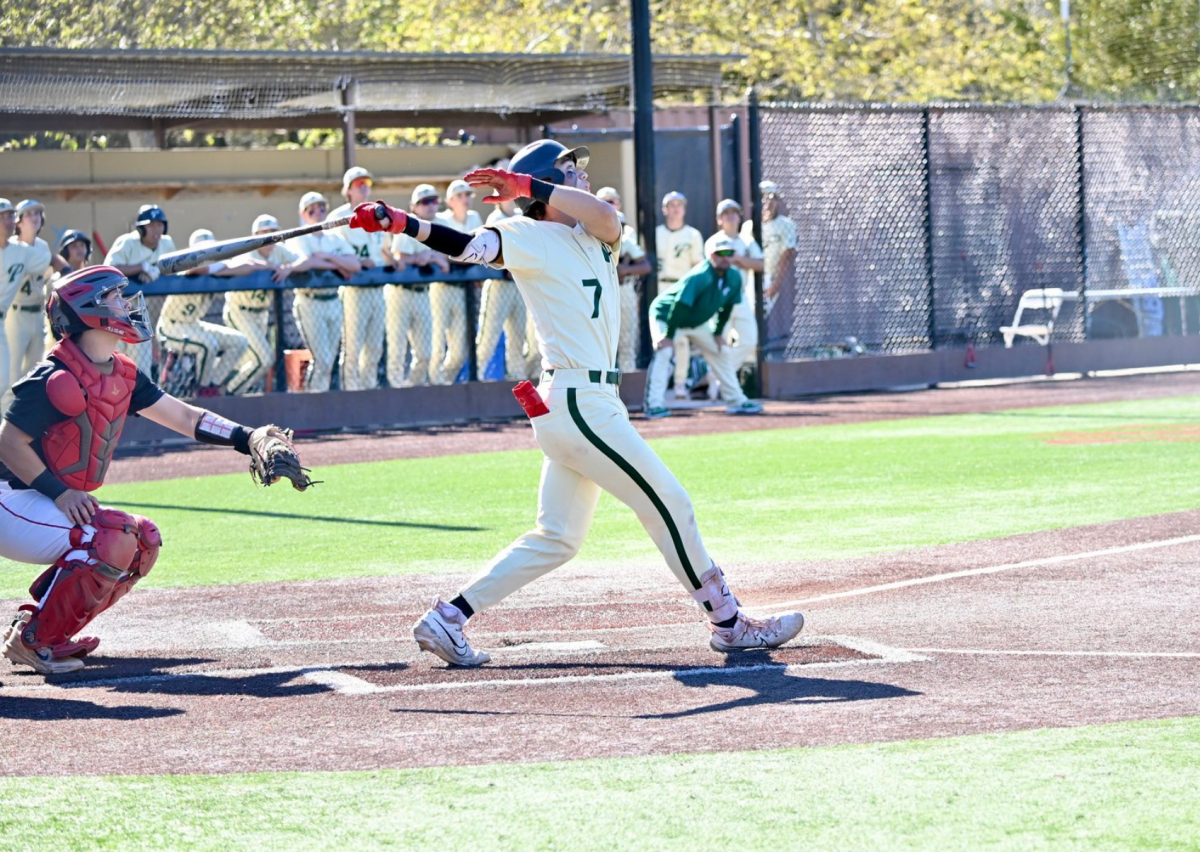

As a former U.S. Women’s National Soccer team member and two-time FIFA World Cup champion, Chastain has had her fair share of coaches. With over four decades of experience under her belt as a player, Chastain now coaches the California Thorns youth girls club soccer team, Bellarmine College Preparatory boys soccer team, and the women’s soccer team at Santa Clara University.

“With time, I’ve really found that I appreciate all of my coaches more and more, and that at every level I’ve had them, they’ve helped me in some way overcome some kind of obstacle,” Chastain said in an interview with Viking. “For me, it’s been learning that all those experiences are really helpful, not just the ones that are easy.”

As the head coach for both girls’ and boys’ soccer teams, Chastain has found more similarities than differences when it comes to her teaching approach regardless of gender. To Chastain, coaching is about recognizing the individual, understanding their circumstances and creatively adapting to help them build their skills.

“We have to allow ourselves to have emotions, we have to allow ourselves to be confident, and somewhere in the middle is a place where we’re going to make a lot of mistakes,” Chastain said. “As a coach, my job is to be as demanding as possible but also as compassionate as possible.”

Chastain says one of the treasures she has found while coaching is using the same approach with “just slightly different tilts of perspective” to get across the same intention and to cater to a player’s method of learning.

“There are boys who are sensitive … and who want you to pat them on the back and tell them that they’re doing a good job,” Chastain said. “And there are girls who really feel like they are confident and they’re strong and I have to encourage them to not be afraid to continue that because socially, girls have [gotten] the bad rap when they are confident.”

I want women to feel that they are welcome to be in coaching.

— Brandi Chastain

According to a 2020 study published by the University of Minnesota’s Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sports, which included information on coaches at 86 universities and colleges that compete in major NCAA Division I conferences, soccer has one of the lowest percentages of female head coaches at only 28.2%.

“I want women to feel that they are welcome to be in coaching,” Chastain said. “I feel like that is slowly changing, but I think the perception, just like a lot of other perceptions about leadership, has come from a male-dominated perspective.”

Although it is crucial to ensure that equal opportunity exists for women, especially on men’s teams, Chastain says that gender should not be the qualifying factor that determines a coach’s eligibility for a given coaching position.

“I think knowledge, experience and leadership skills come through preparation and time, and I think personal confidence is really key,” Chastain said. “For me as a competitor, I just want a coach who is going to challenge me and push me when I’m feeling weaker and to inspire me when I need encouragement … and I don’t think that has a gender.”

Following her departure from the professional soccer world, Chastain said she felt a “big, dark chasm” in her soul because she had been playing the sport for so long — 42 years to be exact. When Chastain decided to start coaching, this hole was filled with her ability and determination to inspire a new generation of soccer players both male and female.

“It’s seeing young players do the thing that we’ve been working on or the thing they thought they couldn’t do,” Chastain said. “That personal empowerment moment is what keeps my heart beating. It’s the reason I want to go out to the field, so that’s what I look for everyday.”

On and off the field, Chastain acts as a role model and mentor to her players, trying to instill a growth mindset within them throughout every practice.

“I try to help my players embrace this: ‘Fall down,’” Chastain said. “‘Be the first to fall down in the most glorious, most spectacular way, and show that getting up takes courage and bravery, but is possible. And then you’re going to face that thing again, and you’re not going to allow it to get the better of you.’”

Lily Welsh

As the final bell of the day rings throughout the school, Paly senior Lily Welsh rushes out of class and makes the 20 minute commute to Webb Ranch, where she spends the rest of the day either being coached in equestrian vaulting or coaching younger vaulters.

Despite being a horseback rider for her entire life, Welsh only discovered vaulting when she was 13 years old after her sister began taking lessons. Her coach, Julie Divita, suggested she come to the ranch one day and try it out, and it was then that she found her passion for the rigorous and artistic sport, often described as dance and gymnastics on horseback.

Nationally, vaulting is regarded as a small and relatively unrecognized sport. The low number of participants and female-dominated atmosphere allows for close connections to form between coaches and vaulters. For many Paly student athletes, the experience of having, or being, a female coach has helped build their own values. For Welsh, Divita has helped shape her into the person she is today.

“She [Divita] was the one who gave me the opportunity to coach and a bunch of other opportunities,” Welsh said. “She’s allowed me to go to competitions and she’s taken me to [Las] Vegas, and she’s just been a really large part of my life as a student, as a person, and as a vaulter.”

Now, as a coach for vaulters aged eight to 14, Welsh attempts to recreate the same type of connections and illuminate the same principles she was taught by Divita with students of her own.

“I hope I’m setting a good example and that they can look up to me as someone to guide them along their journey,” Welsh said.

Welsh teaches a majority female class and has been trained as a vaulter with all-female coaches, with the exception of one coach.

“I think it is important to have strong female role models because we’re in such a male-dominated world, but at the same time as long as you have a good coach I don’t think it really matters,” Welsh said.

As a high schooler and a current athlete, Welsh is able to tap into her knowledge of young mindsets and fuse it with her developed maturity from years of receiving coaching herself.

“I definitely have more of an advantage because I can relate to them more and I know how kids think, because I’m still a kid,” Welsh said. “Just seeing them progress and seeing them find the love for the sport that I found [is the most rewarding thing about coaching].”

At the end of each lesson, Welsh hopes her students take away the notion that it requires more than just vaulting skills to become a successful athlete. She wants to teach them that it is through hard work and perseverance that they can improve both as a vaulter and as an individual.